Is Facebook Killing the Haiti Relief Effort?

June 28, 2011

Published February 4, 2010

During one of my first classes of this semester—over a week after a violent earthquake racked the already impoverished nation of Haiti—the professor asked students to raise their hands if they had donated money to disaster relief in Haiti. Only a few, shy hands sent ripples through an embarrassed silence.

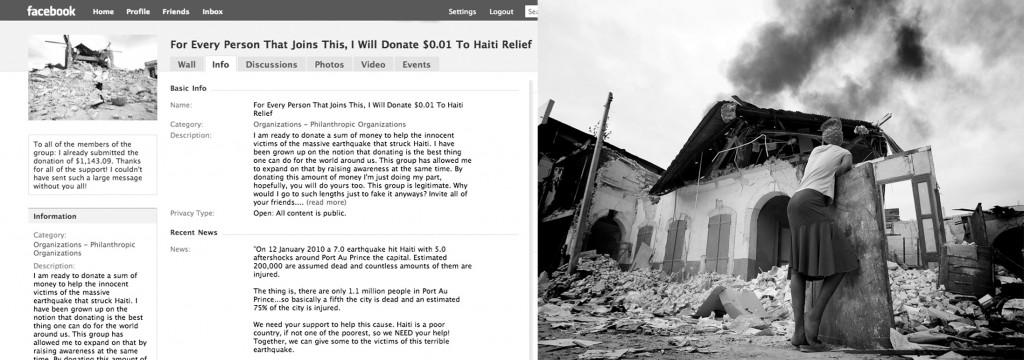

Later that day, still somewhat disheartened by the awkward showcase of apathy I’d been confronted with in class, I logged on to Facebook. I was surprised to find myself faced with a jarring contrast to what I’d seen earlier: “So-and-so and 647 of your friends joined the group ‘We Will Donate $0.01 to Haiti for Every Person That is a Fan.’”

Wait, what?

Okay, so the 647 friends are an exaggeration. But the point doesn’t change: it seems that there are a lot of young people who are eagerly willing to showcase their support for Haiti relief in an online forum, but when it comes to providing any concrete aid to our Caribbean neighbors in need, perhaps not everyone is such a humanitarian.

But aren’t college students are supposed to be the compassionate ones? What about the idealistic generosity of the young? Embittered ex-revolutionaries of our parents’ and professors’ generations might chalk this apparent decline in activism up to laziness, passivity and/or disinterest amongst today’s youth. While this is not a baseless accusation, it would be inaccurate to ignore one definite source of the changing dynamic of humanitarianism. If our generation is falling asleep on the job, then our always available, conveniently cushy mattress is, undoubtedly, the Big Bad Internet.

The fact of the matter is that social networking sites have made it shamefully easy for anyone to put on a revolutionary face, whether or not that person is actually making any kind of a tangible difference. It takes less than a second to post a “Save Haiti!” status on Facebook or to join an online group that dubiously claims to donate such-and-such amount for every member that joins. On the other hand, it takes time and money to supply a verifiably usable contribution to the relief effort, even if it is only a small one. This reality is not always so enticing in an age in which the average Internet-user’s attention span is, according to one BBC report, about nine seconds—the same as that of a goldfish.

Unfortunately, our Google-induced attention deficits are not the only online threat to the relief effort in Haiti. The short-term memory of the Internet itself is perhaps an even larger danger. As anyone who has been to New Orleans since 2003 knows, natural disasters aren’t over when the ground stops shaking. The damage from Hurricane Katrina still looms over the city, and Haiti—a nation far less equipped to deal with large-scale tragedies—won’t see the end of this earthquake for years. The cleanup in Haiti will require enduring efforts from the international community, and although the recent surge in $10 text message pledges to the Red Cross is a commendable first step, our responsibilities as fellow human beings are far from exhausted.

But if you’ve ever heard of Chris Crocker, lonelygirl15 or that YouTube video where the wedding party dances down the aisle, you know that Internet sensations are not prone to long life expectancies. Just like any other online fad, the widespread sympathy for Haiti is faced with the possibility of fading out—and fading quickly. Just as with New Orleans, Haiti’s devastation is in danger of slipping into the background of our collective consciousness. It certainly doesn’t help that below every Tumblr post about Haiti is a paparazzi photo of Taylor Lautner shirtless or a snarky “Team Conan” graphic. Everywhere we look online, there’s something else—and maybe more interesting!—to look at. Not only that, but the Internet has taught us to minimize our efforts, to resolve our issues within the limits of 140 characters. Unfortunately, real life solutions don’t come about with the click of a “Post” button.

But despite the Web’s daunting potential to swallow the Haiti relief effort whole, there is still hope. The Internet is not (yet) an autonomous being; we still have the option of using it for good. As difficult as it may be, humans—the younger generations especially, who hold dominion over the social networks—have the capacity to rein in the Internet’s billions of wandering eyes, as long as we can keep our own focused on important, ongoing issues.

The “Save Haiti!” statuses, tweets and fan pages are only useful if they are accompanied by long-lasting awareness and resulting action. What Haiti needs from the rest of the world is not just emergency relief, but sustainable development—a goal that is not attainable by means of a few Facebook groups. If we stay conscious of the needs of our fellow humans, the Web will, too. If we keep posting, keep encouraging others, keep contributing our time and effort toward causes like Haiti relief and other humanitarian efforts, our online voices won’t be blabbering endlessly in vain.

Our generation still has a shot at making positive change by turning the Internet into something that reminds us of our humanity rather than something that allows us to forget it. It is our responsibility to lengthen our own attention spans when it comes to the needs of others, and if we do, the Internet will most certainly follow suit. College students, ignore the accusations of passivity and laziness from your elders; the age of revolution in the streets has passed. It’s time for an online uprising.