The State of Fordham’s Finances

February 15, 2018

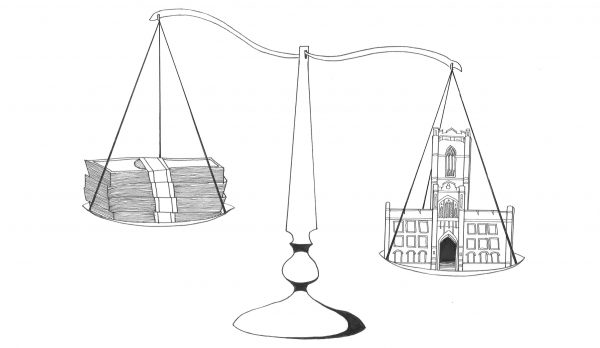

The responsibilities of Senior Vice President, Chief Financial Officer, and Treasurer Martha K. Hirst are as sundry as her many titles, but there is one mantra that contains each: balance. First and foremost, that applies to the university budget. At any given time, its finances, with which she is tasked to manage, encounter unpredictable threats. They arrive in the exigent forms of tuition dependency, US News and World Report rankings and congressional law, armed with the promise to topple, cripple and slash away at a financial plan where the money is already tight. Then there are the people–the faculty, the students, the staff, the trustees to which she is beholden, but nonetheless depend on her ability to balance.

This year has perhaps been the most trying test of her ability since her appointment in 2015, yet she holds bright expectations for the school’s future. On Dec. 4, she sat down with reporters from The Observer and The Fordham Ram to discuss the state of the university’s finances. This is how she sees it.

The Instability of Tuition Dependence:

Near the beginning of her Nov. 2 budget forum presentation, Hirst flipped to a slide that summed up the crux of Fordham’s income challenge, a reality that she believes comes as “no surprise” to most. “We are tuition dependent,” she said, lowering her head. A projection of a gold and crimson pie chart glowed softly over her shoulder. The pieces-three in all, including a thin, black sliver-represented the virtual entirety university’s sources of revenue. Undergraduate tuition: $446 million. Graduate tuition: $201 million. Fees: $17 million.

Combined, tuition and fees make up more than 83 percent of Fordham’s budget. In other words, the university is running on a single crop economy, and, like Ireland on the eve of the Great Famine, the institution’s finances hang in a precarious condition.

“There’s always pressure to diversify those sources of revenue,” Hirst said. That Fordham’s graduate population “ebbs and flows” with enough historical flux to have at one point constituted a larger revenue source than undergraduate tuition is evidence of just that compulsion.

But, Hirst said, nobody should have any illusions about what Fordham is. Yes, it is a research institution, but it does not rake in “gazillions of dollars” for that practice. Yes, it receives grants, but $2.6 million primarily made up of Bundy grants is in no way significant to a $790 million as to ease tuition dependence. Yes, it can and does pull from a respectable endowment, but it has never been an institution with “deep pockets.”

For Hirst, it is about balancing “short-term” and “long-term,” it is about the students currently attending, and those attending “at their 350th anniversary.”

The Financial Burden of a Less than Desirable Academic Reputation:

Such a heavy dependence opens the university up to the numerous hazards that can affect its number one source of income: enrollment. Poor freshman retention and a lack of adequate financial aid can undercut the population of an institution, rendering it financially paralyzed. Smaller private colleges are feeling these effects most acutely in the under enrollment of freshman classes.“For an undergraduate school, that is certainly a scary proposition,” Hirst said during the budget forum.

She also said that combatting under enrollment demands two methods of persuasion: money and prestige. Both are duly earned, and while Fordham has recently suffered a blow to its reputation in the US News and World Report rankings–albeit from 60 to 61–fundraising for financial aid has soared.

As of Jan. 29, the university has raised $121,735,891 of it’s $175 million goal with well over a year before the campaign is scheduled to end on June 30, 2019. Some of the funds will feed directly into the endowment, while others are designated as “current use,” according to Assistant Vice President of Communications Bob Howe, contributing to the operating budget and financial aid.

Hirst noted that Fordham’s academic reputation directly affects a portion of that awarded aid in terms of merit-based financial scholarships. As prestige grows, merit aid shrinks.

As for now, Hirst admitted that “there’s still a very substantial number of Fordham’s students who come whose family incomes wouldn’t necessarily require them to receive on a needs-based financial aid, but are very scholarly and high achievers and students that the university wants here at Fordham.”

At what time will merit aid decrease? Hirst pointed to a goal set by the university president, Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J. “You may have heard Father McShane talk before about this notion of achieving number 50 in the U.S. News rankings by 2020,” she said. “That’s the rubric. That’s the measure.”

The litmus test for its success comes when the scales tip in favor of academic reputation, according to Hirst. When it is seen as an “investment more than a financial burden.”

“Don’t fund him. Fund me.”

In the meantime, Hirst has some “tough conversations” for members of Fordham’s faculty. These, she indicated, might entail a reevaluation of course loads for individual professors as well as a hard look at the sustainability of current healthcare costs. This is not about condemnation, said Hirst. This is about asking the questions that bite with the grit of reality.

“Should we have the top of line health benefits in the country and pass that cost through to students? Maybe,” Hirst said. “Or maybe not.”

Health benefits account for a significant portion of the budget’s expenses, and proved to be a contentious focal point during salary negotiations had between faculty and administrators last spring. In the end, it is “really about balancing competing interests,” according to Hirst.

Her sober approach to discussion, which “makes the faculty nervous,” is present too in the philosophical model she seeks to apply to several aspects of the budget: the model of competing interests. In this construction, academic as well as non-academic programs would compete over the finite amount of resources the university provides.

“People should be–if it’s working right–should be banging on my door everyday. ‘I need money for this. I need money for this,’” Hirst said. Then she decides: “Do we want Fordham to be known for that? Will that make us famous?” In this framework of collegiate Darwinism, a department’s existence begins and ends with those questions.

Such a model tracks with the incentive that drives the university to admit students with high standardized test scores. Every little decision contributes to the reputation of the school. Programs that can generate the repute will swell with financial support. Those that can’t will fall by the wayside.

Hirst suggested that members of The Observer probably knew the feeling of budgetary competition. Administrators too. Hirst noted that last year, the university made millions of dollars in cuts to sections of the administration.

By “maximizing the effectiveness and productivity of all aspects of our workforce,” Hirst said, Fordham can weather the storm of financial instability plaguing universities and colleges across the country.

The Strategy of Shoring Up Savings

As it now stands, the university barely scrapes by with the revenue it collects. By the end of the 2018 fiscal year, Fordham expects to have spent all but $300,000 of its budget. These relatively small remains can do little to stave off disaster, according to Hirst.

“You don’t make enrollment targets, and so your budget’s out of balance. You have to adjust for that. You have a boiler plant blow in a building. You have to adjust for that. You have further impacts on people’s available resources, that we have to spend more on financial aid potentially if we have it. We have to adjust for that,” she said.

Adjustments, however, become increasingly difficult the less on-hand capital an institution has. Fordham’s apparent vulnerability was reflected in negative review conducted by Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC.

The lack of a contingency fund is “a measure of fiscal health,” according to Hirst, and poor health at that. If Fordham was operating at perfect financial stability, it would be “squirreling away” $17 million or more than 56 times the amount it currently does. Where that money would come from is unclear as of now, but nevertheless, this “belt-tightening” is nothing but prudent fiscal strategy, Hirst said.

—

Strategy is ultimately all Hirst can offer. In April, she will deliver a final assessment for the Board of Trustees to vote on the budget for the 2019 fiscal year. Any number of these issues could take precedence in her analysis, though it is also possible that each aspect dominates a different corner of the financial platform Hirst must balance. And while it is surely not a glamourous undertaking–to see every part of the university in its value and cost and risk and potential–it is surely a necessary one.