A Night at the Museum

The simple exterior of the Sir John Soane Museum is a stark contrast to the artifact-cluttered rooms inside. (IZZI DUPREY/THE OBSERVER)

June 13, 2017

Entering the Sir John Soane’s Museum is like delving into the world of a gilded past. Looking at the building from the outside, I did not give much thought to its contents. The four story home stands in the Holborn neighborhood of London, nestled between a row of unimpressive grey buildings. Large windows speckle the white facade, which stands out among the darkness of its neighbors. Statues are visible on either side of the third floor, hinting at the artistic vision of the owner. The building is pretty, yes, but nothing can truly prepare visitors for what awaits them within.

Though I knew little about Sir John Soane before my visit, the knowledgeable museum volunteers, as well as the informative handout I was given on my way in, told me of his interesting past. Soane is regarded as one of the greatest English architects of the 18th century. He specialized in the Neo-Classical style and rose to great prominence within his line of work, becoming a professor at the Royal Academy as well as the architect of the Bank of England.

Soane’s goal was to create something innovative and educational. A man with troubled family relations, he also wanted to prevent his home from being owned by his estranged son upon his death. He accomplished this by transforming his house into a public declaration of his eclectic taste—a small museum that would one day house around 53,000 artifacts. In 1833, Soane negotiated an Act of Parliament which would ensure that his unique home and extensive collection would be preserved as it was at the time of his death. Now, visitors from across the globe can explore the museum and get a glimpse of the world of this historically imperative artist by viewing the pieces of his collection in the exact way he envisioned.

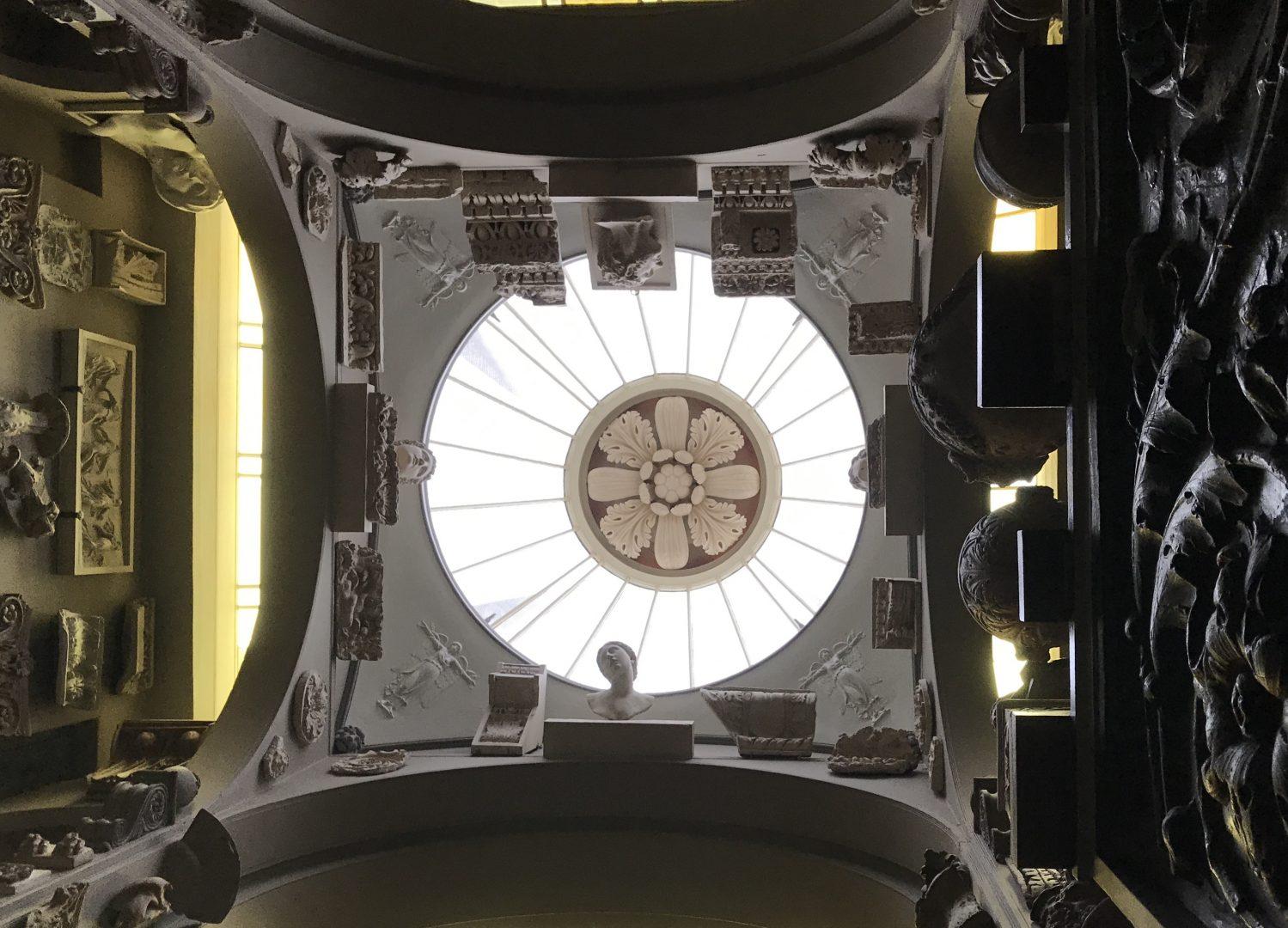

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Soane’s Museum is the unique play between the building’s form and function. Open grates scatter the floors of the first three levels, allowing visitors to glance into the rooms below. While some believe this was simply another eccentric way for Soane to express his artistic ability, this architectural element was actually an attempt to introduce an ingenious heating system into his home, in which hot air would flow from the bottom floor to the very top. Domed ceilings and windowed patches of roof allow natural light to flood the rooms, illuminating the many treasures that Soane accumulated over the course of his life.

Perhaps my favorite element of the home is the distinction between the various floors. Moving through the each level presents visitors with different views of the artist who had walked those same halls. The basement is dark, filled with cold stone statues and monuments to kings of the far-away past. The first floor comes alive with bursts of rich colors, gold ornaments and hints of marble and wood. The second floor seems to explode with light—bright hues decorate the walls of more simplistic rooms that are noticeably sparser than those below.

Hidden treasures lay waiting for museum patrons to discover. Within the “Monument Court,” one could find Pharaoh Seti’s sarcophagus—a glass-encased alabaster tomb which once held the Egyptian king of the XIXth Dynasty. This collectible is not the only belonging of Soane’s which leans heavily on the theme of death and decay; some attribute this to the architect’s prolonged grief caused by his wife’s death, and the museum even houses a replica of the coffin in which she was buried.

A small room located in the basement acted as the office of “Padre Giovanni,” an imaginary persona and alter ego created from the depths of Soane’s own mind. One of the museum employees confidently informed me that the room was Soane’s way of satirizing the rising fashion of Gothic architecture. The picture room on the first floor displays William Hogarth’s “Rake’s Progress,” a set of eight paintings which serve to parody the life of a London man in the 18th century.

Candle-lit showings of the Soane museum occur on the first Tuesday of every month, allowing the house to be illuminated by lighting that would have been used during Soane’s lifetime. The line starts forming outside Sir John Soane’s Museum at 5 p.m. for a 6 p.m. entrance, but only the first 200 people are admitted. If you don’t happen to get a ticket, you can always sit for awhile in the lovely and well-manicured Lincoln’s Inn Fields across the street, but it’s certainly worth it to arrive early for the chance to dive into the mind and world of a remarkable, yet slightly peculiar artist.

Sir John Soane’s Museum

13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London WC2A 3BP

http://www.soane.org

TUBE STOP: Holborn stop by way of the Central and Piccadilly lines