Learn to Resist Read a Book

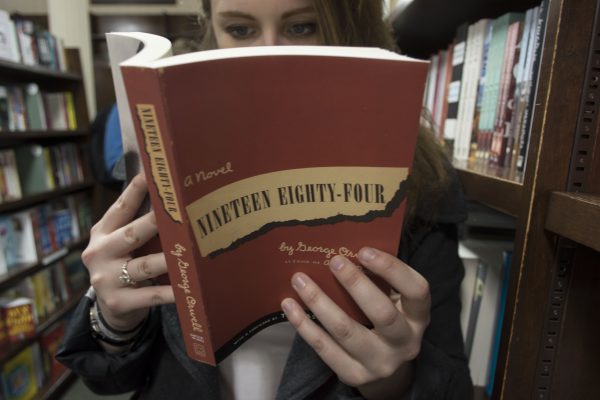

With the rise of Trump, classic dystopian novels have once again become a part of the conversation. (KATARINA MARSCHHAUSEN / THE OBSERVER)

March 9, 2017

Since Donald Trump’s election in November, bookstores across the country have seen a skyrocket in sales of dystopian fiction, namely works such as Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451.” These classical books — published decades ago — outline potential future struggles of the United States in the late-20th and early-21st centuries. In each of these novels, the populace struggles to guard its freedom against a totalitarian regime that has torn away its liberties and pitted classes of citizens against each other. While viewing the authoritarians in these novels as direct reflections of the current administration may seem extreme, using them to better understand the present day is not so far-fetched. In Trump’s America, we can extract wisdom from authors whose works have never occupied such a level of relevance. When re-reading such novels today, the climactic plots, peculiar characters, and intricate settings of these books tend to gain deeper social relevance. We are now beginning to see dystopia as an imminent threat rather than a distant possibility.

While no novel provides a comprehensive representation of the nation’s current politics, we can reference various works and extract snippets with the power to teach meaningful lessons about government and inspire revolution. In Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” the Republic of Gilead enacts discriminatory legislation, oppressing women and minority groups. People of color are reallocated to remote areas and each woman is assigned a specific role with the stratification based on social class. Gilead snuffs women’s mental capabilities and values them solely for their ability to serve men, the accepted ideology being that women are little more than walking wombs. The right- wing government of the United States echoes a similar set of beliefs through its anti-choice legislation like Trump’s global gag rule and Governor John Kasich’s “heartbeat” bill. “The Handmaid’s Tale” illustrates the dangers of extreme-right totalitarianism that has crept its way up on Gilead. It warns that, without significant resistance, a government can easily seize control of the populace by enforcing unjust laws. Aunt Lydia, a character in Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” copes with the recent transition from a democracy to a totalitarian theocracy.

“‘Ordinary’, said Aunt Lydia, ‘is what you are used to. This may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time it will. It will become ordinary.’”

Aunt Lydia’s plea applies to the United States’ current political climate. In the age when “resistance” is a household term, we should take Aunt Lydia’s comment as a warning of normalizing fascism. In understanding the relevance that these works occupy, we can use their lessons to our advantage as tools of resistance. In movements like the post-inauguration Women’s March and Planned Parenthood rallies, Margaret Atwood’s influence is shown by protest signs and chants like, “‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Is Not an Instruction Manual” and “No to The Republic of Gilead!” Feminists today have adopted Atwood’s socio-critical tendencies in their fight for reform and have echoed her pro-choice passion through activism.

In Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451,” the object of contention is not female bodies but literature — books, poetry, etc. Under a different regime of totalitarianism, books, which are considered powerfully dangerous weapons of information, are burned and banned. The government fears critique by its citizens and believes that books are at the root of all free and analytical thinking.

“Fahrenheit 451’s” most flagrant comparison to the current day is Trump’s anti-media rhetoric. Our current administration, like the government in Bradbury’s novel, stifles reading and other forms of informing oneself, as these activities leave room for critical thought. A motif that emerges both in the novel and today is the characterization of media (such as news or books) as “illegitimate.” Similar to Trump’s habit of dismissing anything that exposes his flaws as “fake news,” the governing body in “Fahrenheit 451” outlaws anything that questions society or has the potential to incite revolutionary thought in others.

“A book is a loaded gun in the house next door,” the captain of the book-burning “firemen” says, seeking vengeance against books. “Burn it.” As Captain Beatty further expresses his anxieties about the printed word, he asks, “Who knows who might be the target of a well-read man?”

Because of his fear of the power of education, Beatty and his firemen sweep the nation in search of books, destroying every last page. “Fahrenheit 451” can be applied to our current political climate both in terms of free press and education but it also exemplifies the true capacity to spark change that is held within literature. Halfway through Trump’s first 100 days in office, as resistors lose steam, I urge everyone to pick up a book. Literature is powerful and energizing, as Captain Beatty notes. Your high school English teachers did not assign those speculative reads accidentally. They hoped, as I do now, that you would learn something.