A Grassroots Campaign to Improve Education Worldwide

How One Student’s Experience Abroad Inspired Him to Reach Out to the FCLC Community For Help

June 26, 2011

Before beginning my first day of work half way around the world, I took a morning stroll exploring the area that was now my new home. Walking through farms along red clay paths, I came upon many families getting ready for the coming day. The children bathed each other by the road while their parents prepared an undersized breakfast of cornmeal. Walking by, an awkward silence perpetuated as their wide-eyed faces looked toward me. “MAZUNGU!” they screamed, running toward me to marvel at my weird appearance. Some children went inside and brought their baby brother or sisters out to see this rare white phenomenon. Many believed me to be blessed by God.

A year ago my friend and I spent the summer in East Africa with an organization called Intercommunity Development and Involvement (ICODEI). From fighting HIV/AIDS and poverty to improving education and healthcare, ICODEI provides various vital services to the surrounding rural community of Kabula, Kenya. North of Lake Victoria on the Kenyan-Ugandan border, we taught English, mathematics and science to the elementary students of Epico Jahns Academy. Also, as part of a mobile health clinic, we traveled to remote villages to provide health care and medication for those in need. In return for our services in the area, Rev. Lubanga, a bishop in a nearby diocese, and his family took us onto their farm and provided food, water and shelter.

Although we were fortunate to have these amenities, living on a sugar cane farm was no vacation. The farm and school stand amongst acres of sugarcane, creating a very secluded community far from all the common luxuries of modern civilization. Snakes, especially black mambas, are an everyday concern. Whether they are slithering around the schoolyard or curled up in your bed, you always have to have a watchful eye.

During the rainy season, the weather in East Africa is very bipolar. During the day the sun blazes down on the red earth, sizzling any and all ‘mazungu’ skin. Between four and five o’clock, dark clouds cover the sky foreshadowing the inevitable daily downpours. Surprisingly, the family of four adults and six children managed to shelter themselves in a mud-hut comparable to the size of a McMahon Hall dorm room. Luckily, we had our own designated mud-hut to keep us cool and dry whenever these extreme elements attacked.

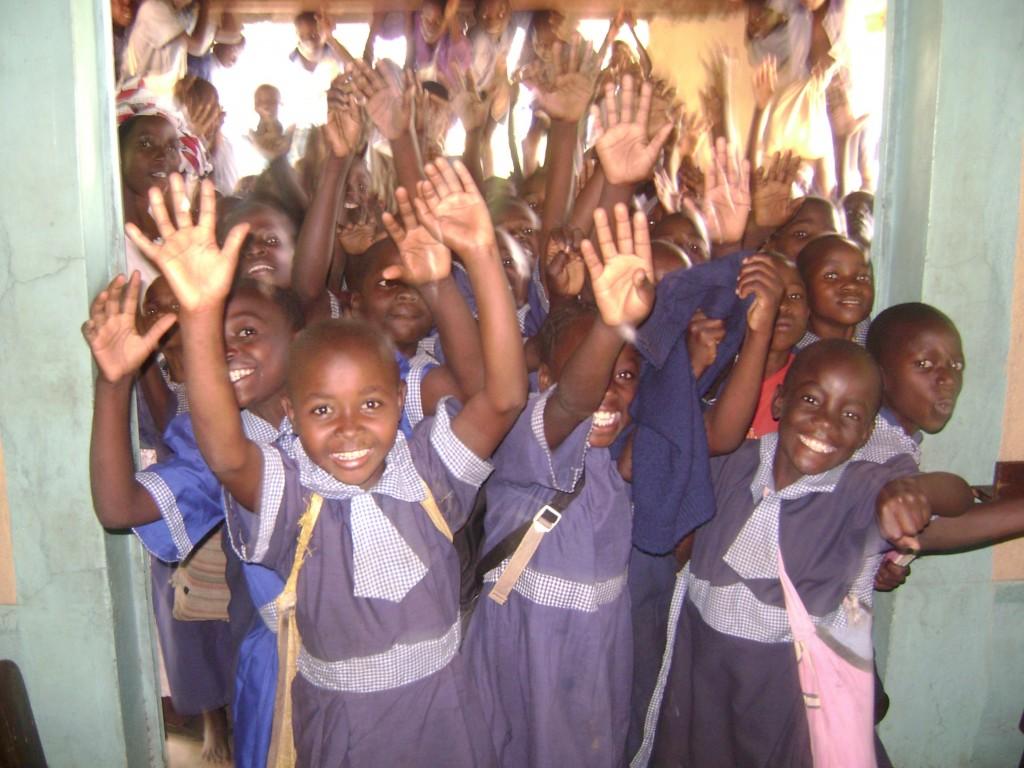

My first day of school at Epico Jahns Academy began just how many schools do in the U.S.: with the national anthem. All of the children, grades pre-kindergarten to sixth, assembled into formation for the raising of the Kenyan flag. After morning announcements, the children scattered to their classrooms and sat patiently waiting for their teachers. I walked through the crumbling mud doorway, under the rusty tin roof and into my second grade classroom. Whether it was the subject matter or my shocking appearance, the children showed remarkable interest and motivation to learn. However, these students lacked some of the fundamental necessities of education. With no pencil sharpeners, my students used open razor blades to sharpen them. As many as three students shared a pencil and six huddled around one of the few textbooks.

Although the school, students and surrounding community are at an unreal level of poverty, Epico Jahns Academy is able to provide an invaluable education for these Kenyan children. Then again, how effective can an education be without a pencil or a book? Despite its shocking disadvantages, this early education gives children their only chance of achieving a prosperous life.

I assumed the poverty would be intense, but I was beyond shocked to discover how bad the conditions truly were. Following my remarkable, eye-opening experience in East Africa, I could not wait for what lay ahead. At first, I did not attempt to solve the problem of ill-equipped schools, but rather looked for other opportunities abroad. Fortunately, a teaching opportunity became available this past summer on the other side of the world in China, and I traveled to the Sichuan Province and taught English and phonetics at Xaioyan New School of English Education.

After a 16-hour flight, 12 time zones, and a two-hour drive southwest from Chengdu, we arrived in the village of Da Hua; far from China’s eastern coast, westerners (or lao wai as they referred to us) are hardly seen and English is rarely heard. Even though it is more developed than Epico Jahns, Xaioyan School is in a similar predicament, desperately in need of basic materials that make class possible. This time, after returning home, the overwhelming needs of students compelled me to take action. Millions of schools around the world and their students need a pencil to write with and a notebook to write in. Living and working abroad reaffirmed the shortcomings prevalent from Africa to Asia.

In reaction to my experiences in remote developing communities, I have established a grassroots campaign aimed at supplying deprived schools with these basic supplies, starting with Epico Jahns Academy. From office supply stores to personal contributions, donations of any kind will quickly change one school after another. I hope Fordham University and its students grab hold of this tangible problem and provide help for those children in need.

Donation boxes will be outside Quinn Library and Lincoln Center Book Store on Oct. 15. Each pencil or notebook will make a startling difference in promoting proper and effective education around the world.