Savage and Beautiful

July 27, 2015

“If only we could be this extravagant everyday,” whispered a young woman with short teal hair and a septum piercing as she passed Alexander McQueen’s gold-feathered coat. It was featured in his Fall/Winter 2010 collection, which was left unfinished due to his tragic suicide. This special collection consisting of 16 pieces had only been partly completed by McQueen himself. Savage Beauty, an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, allows visitors to wander through the mind of Alexander McQueen—the renowned designer who pushed the boundaries of fashion.

To many, Alexander McQueen is best remembered as the mastermind behind Lady Gaga’s recognizable armadillo boots or anything in her “Bad Romance” music video. But, celebrities aside, McQueen was an iconic man who broke fashion and social constructs.

“There’s something very Edgar Allen Poe-y about this,” one woman said to another as she walked through an eerie tunnel of bones that led to the Romantic Primitivism room—one filled with dark animalistic inspired pieces. McQueen once said, “People find my things sometimes aggressive. But I don’t see it as aggressive. I see it as romantic, dealing with the dark side of my personality.”

Following its success at the Met in New York City, Savage Beauty has found a home in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum until August 2. The exhibit contains nine rooms that serve as the window into McQueen’s inspiration: London, A Romantic Mind, A Gothic Mind, Romantic Primitivism, Romantic Nationalism, Cabinet of Curiosities, Romantic Exoticism, Voss, Romantic Naturalism and his last full collection, Plato’s Atlantis.

McQueen didn’t think of his clothing as only decorative, but also performative. For example, “Voss,” or the asylum show, called for the fashion enthused audience to sit around a box with a two-way mirror. In the beginning they could only see themselves, yet as the show started, they saw the models trapped inside. Each model struts in and out through two entrances in the back and around a large rectangle in the center, but they couldn’t see the audience at all; when they looked in the mirror, they only saw themselves. McQueen portrayed a powerful sentiment about beauty ideals in this unconventional show that works the same way as a dance performance–there may not be one single answer to how thing are supposed to be perceived, but all can relate to the movement. In the finale, the box in the middle erupted to unveil a naked plus-sized woman covered in flowers and wearing a gas mask modeled after Joel-Peter Witkin’s “Sanitarium.” “It was about trying to trap something that wasn’t conventionally beautiful,” McQueen admitted, “to show that beauty comes from within.”

My favorite dress spun on a platform in the middle of the cabinet room. Resembling a straight jacket, two mechanical arms spray-painted this strapless number in his Spring/Summer collection of 1999. The dress was in no way the most extravagant or the most wearable, but in Shalom Harlow’s performance, she communicated a sense of sacrifice and release. It was a human experience. “I have to force people to look at things,” said Alexander McQueen, which he surely accomplished throughout his career.

“I get it!” shouts a little girl with pigtails as she pulls on her mother’s skirt after watching a hologram of Kate Moss ethereally twirling from McQueen’s collection, “The Widows of Culloden.” I had to agree with this excited little girl because watching the movement of the dress was much more interesting than seeing it draped lifelessly on a mannequin right outside the glass pyramid that held the projection.

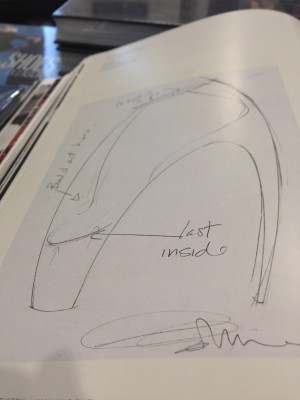

The more I thought about it, the more I realized his final result worked much like my own creative process. A dancer’s mind works in terms of spatial awareness and presence. Dancers and McQueen both use bodies as tools to create a relationship with the audience and convey an emotional message. Since Savage Beauty allows spectators to peer into McQueen’s mind to see the steps it took for him to bring his creations to life, I wish there were more chances to see his articles in motion because that must have been an integral part of the process. He thought of everything that needed to be thought of: the silhouette, music, shoes, patterns, message and movement. The final product wasn’t just the dress. It was used to express real human emotions.

“Fashion is so much about kissing ass and I don’t,” McQueen once said. By the look of his lavender jumpsuit with crocodiles on the lapels, I can attest for that statement. The exhibition not only revealed his creative brilliance, but exposed his refreshingly unconventional view on life. “I’m not big on women looking naïve” is written on the wall as bystanders pass a grand black-feathered dress complete with a full skirt and a hood. He celebrated women, culture and inner beauty; for which the fashion world isn’t typically known.

“I’d just hope this stays on,” a white haired woman said as she nudged her best friend who replied, “You have to be a certain type of person to wear this stuff.” This may be true but you definitely have to be another certain type of person to design it. Alexander McQueen was that person.