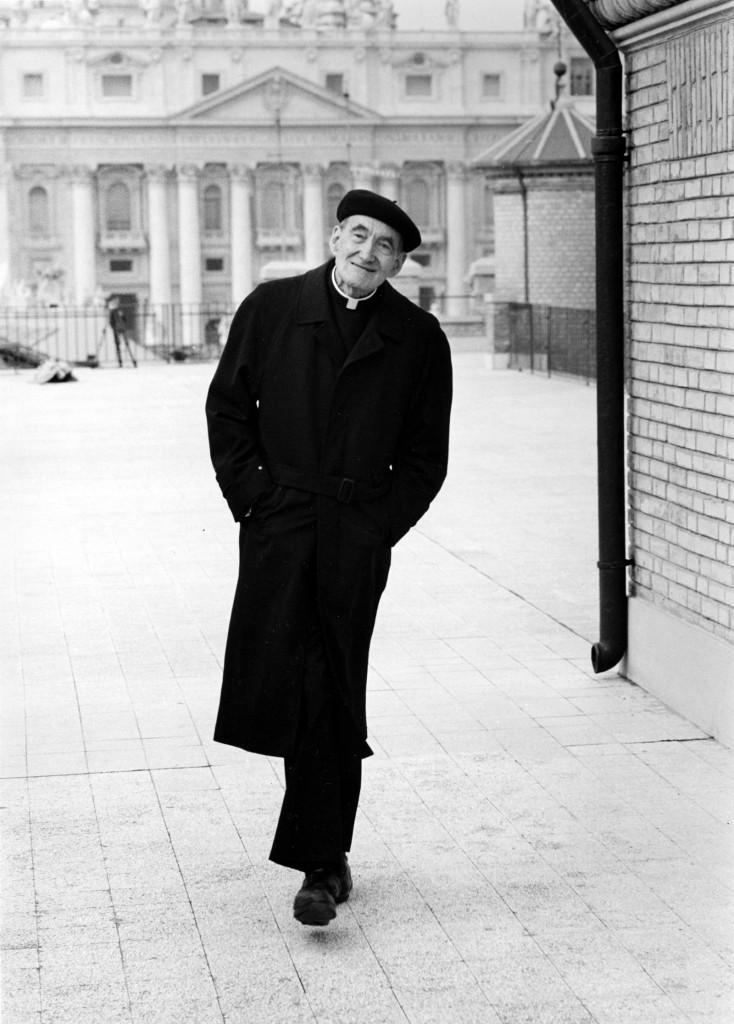

Avery Cardinal Dulles Leaves Behind a Legacy of Service

Faculty Applaud Dulles for Taking on Controversial Topics

June 6, 2011

Published: December 29, 2009

“Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., was a man, a priest and a theologian for whom superlatives are wholly inadequate,” Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, said in a statement. Dulles, the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society at Fordham, died at the age of 90 on Dec. 12, 2008. Before his death, Dulles enjoyed a long and fruitful career as a writer, scholar and theologian. He was the son of John Foster Dulles, former secretary of state under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The family was Presbyterian, but by the time Dulles entered Harvard College in 1936, he had lost faith in the Presbyterian church and considered himself agnostic, according to the New York Times.

“It’s a pretty remarkable story,” said Rev. Robert R. Grimes, S.J., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC). “A man from a very prominent Presbyterian family goes to Harvard and decides to become a Catholic.”

Dulles wrote in his 1946 book “A Testimonial to Grace” that it was the sight of a bud forming in a tree that inspired his thoughts of conversion. He wrote that the “little buds… followed a rule, a law of which I as yet knew nothing.”

Grimes said, “Avery was always very intellectual. You read about saints who had these grand emotional conversions… I can’t imagine that was Avery. The way he describes it… it’s the ideas that he’s reading at Harvard… he is reading the philosophers, the great theologians, and he’s saying, ‘What is truth and why am I alive and what is the point of all of this?’ And what he finds is the answer leads him directly into the Catholic Church.”

According to a brief biography published on Fordham’s Web site, Dulles became a priest of the Society of Jesus (Jesuit) in 1956. One of Dulles’s first teaching positions was in 1951 at Fordham University, where he taught philosophy for two years. He completed a doctorate in Sacred Theology in 1960 at the Gregorian University in Rome. He then returned to America and spent 14 years teaching at Woodstock College in Maryland before moving to the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. to teach systemic theology. He retired from teaching full-time in 1988, and returned to Fordham to accept the position of Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society.

“He was offered a number of chairs, and he came here for one year,” said Sister Anne-Marie Kirmse, O.P., Ph.D., Dulles’s assistant of 20 years. According to Kirmse, Dulles had planned one trial year at Fordham, but did not initially plan to permanently fill the position.

“He came and he saw and the rest, as they say, is history. He started at Fordham and ended at Fordham,” she said.

As the McGinley Chair, Dulles was a university professor, meaning he had the opportunity to write, teach and lecture without being tied to any department, according to Grimes. Dulles taught one class per academic year and gave a series of lectures, which have since been published in a book called “Church and Society: The Laurence J. McGinley Lectures, 1988-2007,” Kirmse said.

“It was a service he offered to the university and to New York,” Kirmse said. “He took on some topics that were very controversial, such as the death penalty and the ordination of women.”

Throughout his lifetime, Dulles authored 24 books and over 800 articles, including “Models of the Church,” a book that identified and described five “models” or formulations of the Christian church.

“He is laying out different ways that human beings can understand what revelation is,” Grimes said. “What he’s setting out [are] the different valid understandings of the way in which God reveals God’s self to us.”

“‘Models of the Church’… revolutionized the Catholic theology of the Church,” said Mark Massa, S.J., the Karl Rahner Distinguished Professor of Theology at Fordham.

Kirmse said, “[‘Models of the Church’] was published in 1974, within 10 years of the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican (Vatican II). Before that, the Church was only seen as an institution. [The book] got to the people in the pew, so to speak. [Dulles] brought the teaching of Vatican II to the country.”

Dulles was a proponent of an open dialogue on religion. Since the late 1960s, many Catholics have called for the Church to revise its positions on issues such as contraception, women in the clergy and sexuality, and Church leaders continue to be criticized for resistance to revisions. While Dulles considered these positions, he resisted the efforts to change the Church, according to Grimes.

“I think he’d say something like, ‘The problem is not seeing what the Church really is, it is seeing the faults…of a human organization, rather than understanding that this is not a human organization at all,’” Grimes said. “There is something profoundly spiritual about it.”

In 2001, Pope John Paul II elevated Dulles to the position of cardinal within the Church. At age 82, Dulles was two years older than the age limit for cardinals to participate in the conclave that selects the pope, and was excluded from the process. According to Grimes, the title was largely a tribute to Dulles’s extensive career.

“In every consistory when the pope names cardinals, there are usually one or two who are over 80,” Grimes said. “They are usually theologians the Pope wants to honor.”

The title also helped bestow Fordham with a unique position. Fordham became the only university in America to ever have a Catholic cardinal on staff.

“As a cardinal, he brought a sense of the universal church right here to our own place,” said Kirmse. “He was a link to the Church in Rome, so it kind of brought Rome home to us.”

Later in his life, the Church was confronted with a series of scandals, in which many members of the American Catholic clergy were accused of sexually abusing children. In 2002, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) met in Dallas, Tx., and assembled the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, also known as the Dallas Charter. The charter established a “no tolerance” policy for priests accused of abuse. Under the charter, priests could be barred from the altar if credible accusations of abuse were made against them, whether or not the charges were proven true. Dulles argued, both in Dallas and in an article published in America magazine, that the policy would deny priests any right to due process.

“I… admire him for standing up to the bishops when they gathered in Dallas to deal with the crisis of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church in America,” said Michael Tueth, S.J., associate professor of communication and media studies at FCLC and an associate chair of the department. “He didn’t hesitate to speak the truth when he thought that the Church was going in the wrong direction.”

Massa spoke of watching coverage of the Dallas Charter conference on television. He said as Dulles began to speak, all eyes in the room turned to him.

“At the Dallas Charter his was the voice that everyone in that room wanted to understand,” Massa said. “When he spoke, Rome listened and his fellow bishops listened.”

Dulles’s friends and colleagues remember him as an influential theologian who was open to discussing various interpretations of Church doctrine and theological issues.

“He brought to the university a theologian of world importance, profound learning, especially in the area of ecclesiology [the study of the Church], and tremendous wisdom and good sense,” said Joseph Koterski, S.J., associate professor of philosophy at Fordham.

“Avery and I were not on the same side on a lot of theological issues,” Massa said. “But I remember that he could listen and remember what you said and he respected it.”

“[Dulles] always wanted to work within the pale of orthodoxy, but was always willing to listen to other ways of understanding the tradition,” said Terrence Tilley, professor of theology and chair of the department at Fordham. “One of the things he taught me by the way he worked was that your intellectual opponents are not your enemies but your friends. They help you to understand the truth you are trying to articulate better, because they are seeking the truth with you, even as an opponent.”

“He tried to influence through his writings,” Kirsme said. “He wrote over 800 articles in his lifetime, and close to half of them were written in the last 20 years. He tried [through] his writings to bring out different aspects [of issues] that perhaps people were not seeing, or not seeing clearly enough.”

Grimes said, “He was a wonderful, wonderful man… and I feel incredibly grateful to God to have known him.”