Strong and Stimulating Photos Make Opie’s Exhibit a Must-See

Community and Identity Are Key Issues Presented in Guggenheim Retrospective

June 6, 2011

Published: December 11, 2008

First off, I know absolutely nothing about art. I’ve never really gone to any art shows or galleries. I went to the Guggenheim Museum exhibit, “Catherine Opie: American Photographer,” with an open mind and no previous knowledge of her work. The result: I was blown away. Opie’s work is uncompromising, shocking and thought-provoking. Every piece I saw offered something new and gave me a greater appreciation for the art of photography and for the issues of community culture that are addressed.

Moving between stark black and white photographs and vibrant, stimulating color photos, Catherine Opie examines the ideas of sexual and cultural identity. The exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum collects works from all aspects of her career. Spread over Opie’s entire career with a focus on her studio portraiture and landscape photography, the collection at the Guggenheim is the most comprehensive presentation of her work to date.

The first part of the exhibit emphasizes Opie’s black and white landscape photography with four different series of pictures. When entering the gallery, four photos of Wall Street are lined up side by side. However, there is a noticeable lack of people in any of the photos. One focuses on an empty plaza with a “No Standing” sign towards the left of the frame. The other three all show empty alleys strewn with garbage. While at first I didn’t realize what the point of the photos were, I saw a pattern of the juxtaposition of poverty in an area of wealth. Many of Opie’s landscape photos invoke a similar reaction. Patterns and meanings are difficult to discern at first, but your attention is rewarded when the answers reveal themselves.

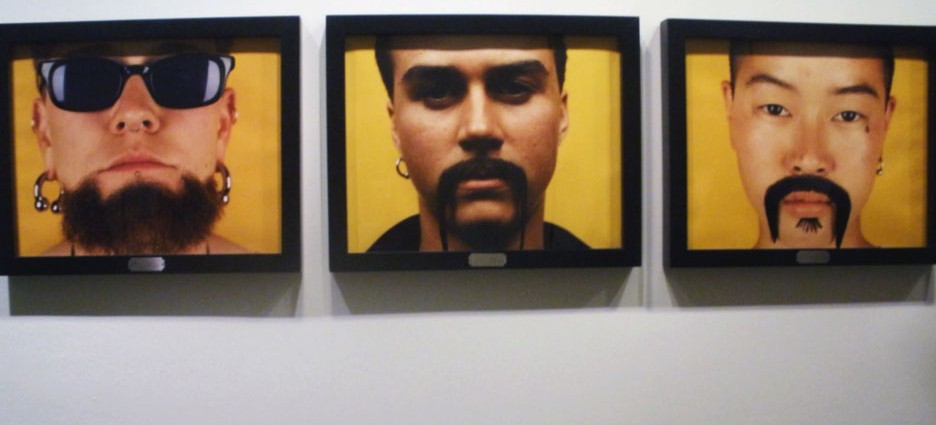

The photos switch from Opie’s relatively laid-back landscape work to a much more in-your-face exhibit. Switching to color, Opie’s Portraits, the work that first gained the artist distinction in the early to mid-1990s, celebrates the homosexual, cross-dressing and transgender subcultures of Los Angeles and San Francisco. As the subjects stared intensely out of the photographs, I felt that the members of this subculture were forcing me to confront any biases I might have and were challenging me to show acceptance. However, even though their eyes seem to be digging into all who look at them, the photos show a warm portrayal of this subculture that is all but invisible to the dominant culture of America. Opie personally knew all of the people used in Portraits and calls them part of her royal family.

Opie doesn’t just stand behind the camera for this series—she also includes a couple of self-portraits in this exhibit. The first photo is the most powerful image of the exhibit. It is of Opie with multiple needles inserted up the length of both her arms and the word “pervert” freshly carved into her chest. When I first saw this portrait, I was very surprised and somewhat disturbed by it, which appeared to be Opie’s intention. The next self-portrait of Opie shows her breast-feeding a child that strangely seems to be a year or two old. The faded scar of the word “pervert” can still be seen, but it appears more like beautiful calligraphy than it did in the first piece. Both these photos moved me between shock and fascination, an emotional tug-of-war that Opie excels at creating.

The next exhibit, Domestic, is a depiction of lesbian couples in a family setting from all walks of life. The gallery does an incredible job at displaying a complex but contemporary family setting. It seems that Opie is making a point about how families are more about relationships and community than having any specific makeup or guidelines. This series segues into another set of photos called Houses. Looking into Opie’s interest in domestic architecture, these pictures all display entrances to mansions in Beverly Hills and Bel Air. The closed gates, doors and high-tech surveillance effectively show the barrier the rich put up to separate themselves from everyone else.

In and Around Home finds Opie working within her own domestic life and that of her neighbors. Working with juxtaposition once again, many pictures address similar topics in home life and the international world. Within the same series, Opie also displays comparable actions but recontextualizes their meaning by grouping them together. In one case, three photos of people gathering are placed side by side. However, they all have different meanings as one is a protest against a sex offender, the second is a homecoming party and the third is a parade in honor of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This exhibit certainly showed me the similarities that seem to exist between most communities. I felt that even though the photos were taken in Southern California, they could just as easily have been taken within my own neighborhood.

“Catherine Opie: American Photographer” will be on display at the Guggenheim Museum until Jan. 7. There’s also a free audio tour that comes with the price of admission. I would definitely recommend this exhibit to anyone who is a fan of art or photography. Even if you don’t really have an interest in art, you should still check out the exhibit. Opie’s work is very strong and challenging, but that’s the source of the enjoyment. This isn’t coffee table book artwork. These photographs are stunning and will stimulate you both emotionally and intellectually.