Baseball’s PED Problem Runs Deeper than Greed

September 9, 2013

Pundits, bloggers, broadcasters and fans watched the annual All-Star festivities in mid-July at Citi Field ballpark in Queens, New York. But this was the calm before the storm: the week of celebrating baseball’s biggest and best in 2013 just before suspensions came crashing down on a number of players. Everyone waited for the news to break about Major League Baseball (MLB) and its newest performance-enhancing drugs (PED) scandal. And soon enough, the news came: by mid-August, 14 players were suspended for violating the sport’s drug policy.

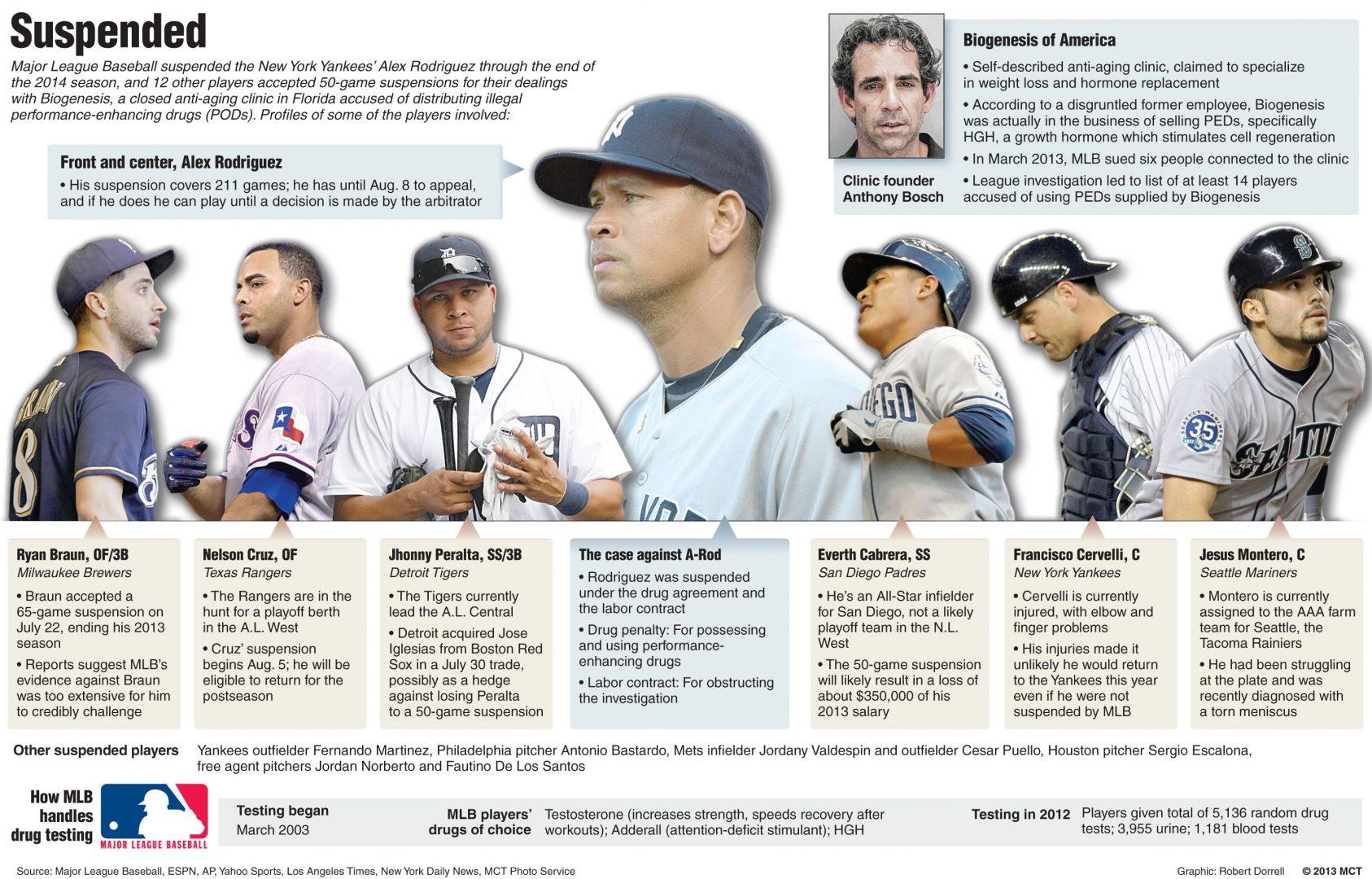

MLB Commissioner Bud Selig launched an investigation into Biogenesis of America, a now-closed South Florida anti-aging clinic, earlier this year. The investigation came after the Miami New Times reported that the clinic was providing baseball players with banned substances. The original article, written by Tim Elfrink, helped to expose Anthony Bosch, a fake doctor and owner of Biogenesis. Although Bosch claimed he was a doctor, he never received a medical degree yet somehow gained access to drugs such as Human Growth Hormone, which he supplied to players through intermediaries.

After months of gathering documentation reflecting the drug sales, Selig had enough information to suspend 14 players with a range between 50 to 211 games. It was the second largest outing of doping MLB players since The Mitchell Report scandal in 2007, which tied 89 current and former MLB players to PEDs.

The discussion around PED use in baseball is largely centered on characterizing the offenders as greedy, money-grubbing, dishonest; completely glazing over the larger issue for many of those embroiled in scandal. Out of the 14 players suspended, the overwhelming majority are from the Dominican Republic, such as Cesar Puello, Nelson Cruz and Antonio Bastardo. According to The World Bank, about 40% of the population in the Dominican Republic is in poverty. The country, now widely known amongst both its citizens and fans of MLB as being an influential source of major league talent, has a whole host of families desperate to escape these conditions.

To hear it told by WAMU reporter Patrick Madden, it’s less an issue of integrity and love for the sport, and more one of desperation. “[T]he incentives are so great down there,” Madden said, “it’s one of those things where you just have to follow the money. I mean, the average signing bonus for a Dominican prospect is $100,000—the average income for a Dominican family is $25,000. So to make it in baseball—it’s a way to really succeed, and that means that the incentives to cheat are high.”

Many Latin American players, especially in the Dominican Republic, quit school rather young in order to join baseball academies built by MLB teams. Hundreds of boys join these academies by the age of ten, and only a handful of them get picked to join MLB teams by the time they are 16 to 18 years old. Some steroids are simply available over the counter in the Dominican Republic, and young players may look to the steroids to give them an edge. They may be advised that there is nothing wrong with the substances they are taking or they may know full well that what they are doing is wrong. Either way, they look to the steroids to make themselves a better athlete which will, in turn, grab the attention of a MLB team who will hopefully sign them to a contract. For them, the contract means removing themselves and their family from poverty.

One of the suspended players, Fernando Martinez of the New York Yankees, was a top prospect for the New York Mets organization when they signed him in July 2005. When he was signed at the age of 16, Martinez was physically superior to his peers. He was a heavy duty, 6-foot-one-inch hitting machine. Every Mets fan knew who he was and expected great things from him. Martinez had received many awards and honors, including being named one of the AFL Rising Stars in 2006, and being the Caribbean Series MVP in 2010. Once he made it to the big leagues, however, injuries plagued Martinez, and he was eventually dropped by the Mets. A month later, Martinez was picked up and a year later dropped by the Houston Astros. He was eventually picked up by the Yankees, but as a career major leaguer in 99 games Martinez had a dismal .206 batting average.

Although it’s not known when Martinez took the PEDs, the timeline of his performance to date heavily suggests an early reliance on the drugs to produce more and gain back the attention of MLB teams. Martinez, having risen to celebrity back home in the Dominican Republic, could send paychecks to his family while younger kids see his success and idolize him. Even having failed to stick as a productive major-leaguer, Martinez’s story provides a sad template for kids in an even sadder situation.

The MLB will continue to test and investigate players in order to put an end to the use of PEDs. But the money and lifestyle associated with the MLB will indeed lure young, impoverished players to keep doping up to have that life. In the 2007 Mitchell Report, players were getting steroids from clubhouse employees; now they are seeking it from a motel-converted-clinic in South Florida. Clinics and dealers will always be around to supply substances to those players who are convinced they need it for an improved life, and so, as long as the true root of the problem remains, the cycle will continue to go around.