Home

April 18, 2012

Margaret Lamb/Writing to the Right-Hand Margin Prize Co-Winner (Nonfiction)

My home is small and rectangular. It comprises a kitchen, living room, dining room, three bedrooms, and two bathrooms above a basement and a garage, all wrapped in beige siding and maroon shutters, and a roof that keeps out the water. There is a green yard, and, in the middle of our side yard, there is a large rock on which I used to play when I was little. There is no white picket fence. Anyone is welcome here. I have led boyfriends, school friends, honor-society members, learning communities, Emmaus retreat parties, and one Peruvian family to this house without apprehension. When I left for college, my dad approached me the first time that I returned home and asked, “Do you like coming home? Do you feel comfortable coming home?” Home is quaint. Home is filled with Italian smells and often someone yelling. When I wake up at home in the middle of the night, I’m never scared shitless as I am when I wake up almost anyplace else. And, no matter how awake I am, I always know where the bathroom is. In that way, home is convenient.

But living away for four years changes things. When a stomachache emerged one week during my senior year of college, it didn’t matter that I wasn’t home. I did what any sensible adult would do, I dealt with it, eating accordingly and scurrying off to my personal bathroom, the location of which I am well aware. When lower-abdominal cramps began to worry me, I went downstairs onto the comfortable-enough couch of my friend Sam, so that I didn’t have to lay in bed alone. Sam will hug me and listen to me and, if he’s feeling particularly fond of me, give me chips. That’s the thing about home: you can find hugging arms and a stable bathroom other places, too. In some ways, home is transportable.

When I woke up the next morning to even more nausea and more pronounced abdominal cramps, I needed more than Sam. I went and found Caitie, an EMT in the building, who listened as I recited my symptoms and offered me a Snackwell cookie.

“You can either go to Barnabus or wait it out,” she offered.

I was terrified of St. Barnabus Hospital, having heard only horror stories, and I wasn’t especially keen on the idea of going alone. But isn’t that the essence of adulthood, going to the hospital on your own? Unsure of where to turn, I called my mother.

“Come home,” she implored me over the phone. “You might have appendicitis.”

In the Danbury Hospital Emergency Room, after my vitals were taken and a cursory exam was performed, I sat behind a curtain of green with flecks of gold and rectangles of gray-brown. The design looked as if an artist once had a vision that was marred by exhaustion and a few too many glasses of straight scotch, and the destroyed afterthought was then transferred onto a sheet. My makeshift gown was decorated with a snowflake pattern print even though October had just started.

As I’d imagined, the emergency room was bland and chilly and beeping, and it exhausted me. My IV dripped. Nurses rushed around. It was a pretty standard emergency-room experience.

“How’s the pain now?”

“I’m not in pain,” I tried to tell the nurse, her tight eyebrows wincing back at me. It’s not pain in my side, it’s discomfort, and it was making me nauseous –swaying, swaying—so that I wanted to eat but couldn’t and instead ended up doubled over, heaving, only coughing up clear strings of mucus.

As she stared back at me, I realized that there was no credibility on my end, because I didn’t have life-threatening symptoms. “But I’m really nauseous,” I told her again. “I know it’s not a stomach bug and I haven’t been able to eat since Tuesday.”

They gave me two super-sized, Tang-flavored drinks, while they injected antinausea medication into my IV. They laid me down, put on breast shields, and slid me through a CT scan machine, the robot voice from the gastrointestinal machine telling me when to hold my breath and when to exhale.

“Breathe now.” The smiley face above my head lit up green.

“Hold your breath.” A different smiley illuminated in orange.

“How’s the pain now?”

Danbury Hospital is enormous: it is contained by four walls, but it prides itself on having “more than a million square feet of healthcare” and 371 overnight beds. It delivers 2,500 babies every year, which is just a few hundred heads shy of the population of Danbury High school. I was tucked away into a corner of the emergency room for two hours, the green curtain substituting for two walls. My mother was sitting across from me, the abstract colors behind her like the backdrop from a bad portrait studio, and she was probably thinking about cleaning the house. She had picked me up from the train, driven me here, held my clothes. I felt bad that she was here. I was sorry for having ruined her plans for the day, but I was also grateful that I didn’t have to go through the hospital’s admission process alone. As I was considering suggesting that she leave, even just to get a meal or a coffee, she perked her head up and looked at me.

“You could do this on your own,” she said. “You’re twenty-one now; you don’t need me to go to the hospital with you.”

Tears came to her eyes as my hospital gown slid further down my shoulder.

I could have done this alone, but I didn’t. I wanted to come home.

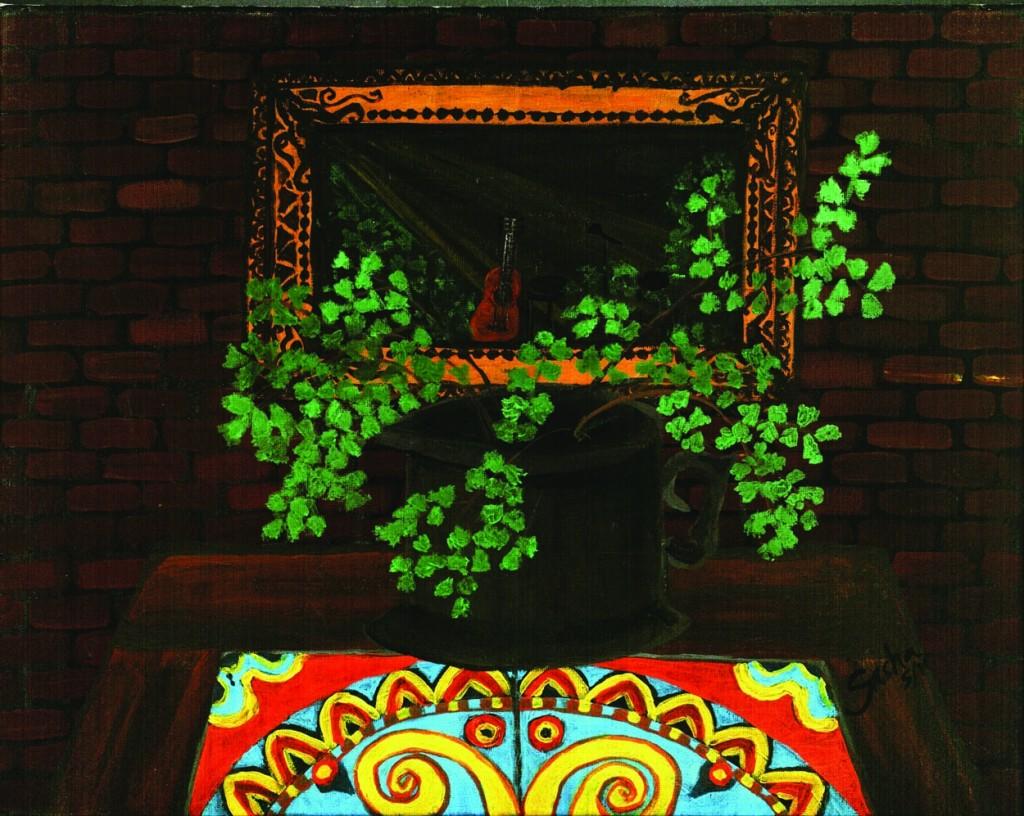

I am home, again. After last night at the E.R., I woke up this morning to the smell of eggplant frying and sauce simmering, the precursor to a house filled with Bronx Italian-English and laughter. As I lay in bed with my warm, neon linens enveloping me, my mind drifts to the sheet that hung in front of me in the emergency room. Maybe the artist who sketched the senseless pattern knew his work was doomed, only to hang limply and then be stared at by eyes that don’t really see anything, 371 people in 371 beds, all with their trains of thought lingering above them. Maybe the artist stared at his canvas and thought, this doesn’t matter, and flung wads of paint of green and gold onto a sheet of speckled oblivion. Maybe he felt the moments of his career collide into a vat of senselessness as he pushed the brush against the canvas in small strokes, redeeming his dignity with rectangles of gold.

In the realm of the emergency room, with half-dead and mangled bodies whizzing past me, I realized that I was not that important. I was the least urgent of the many bodies in the space where there is always blood to take, x-rays to read, body parts to re-assemble. Each day, the doctors with straight faces tell patients what is —or isn’t—wrong with them. The green-and-gold-flecked curtain hangs motionless even now, sheltering new bodies each hour, as the world spins on around it.

When I wake up at home, though, I matter. My mother asks how I feel and insists that I eat something to settle my stomach, otherwise I’ll never get better. She orders me to stay home for the night so that I can go to another doctor on Monday, as I reach for ceramic dishes, arranging them on the dark-wood table in septuplicate. I am welcome here, as is the family that will come later, and it feels as if everyone is concerned about one another’s well-being, concern of the genuine sort, rather than the billable-by-the-hour kind. This, I think to myself, is why I wanted to come home.

This is what home is. A place steeped in tradition and sameness: the same tickle-me-pink paint covering my bedroom walls since my dad took me to Home Depot, I was still an only child then, and told me to pick a hue to for my big-girl room. The motto of “keep doing what we’ve always done” that fails our country’s government ceaselessly is granted great success within these walls, where we can’t imagine life any other way. Home is not a place for revolution or lofty ideals. Home is not pulsing with boundless energy, as is the college campus that houses me temporarily. Home is not a friend’s couch or any cold bed, blockaded by a green, abstract sheet. But home, regardless of where it is located geographically, is filled with the same pink walls and concern and food and routine that still works, just as it always has. And when dusk returns, we will return tonight to our own beds, each tucked away in our respective three rooms (not 371 like Danbury Hospital, or 344 like my dorm) each sheltered by four plaster walls, with no hanging curtains of green and gold.