Brooklyn Zinefest Welcomes All Things Weird

April 18, 2012

The weirdos must be heard. The New Yorker wouldn’t publish them. Rolling Stone wouldn’t publish them. I certainly wouldn’t publish them. And so they publish themselves, and bare it all for all the world at the Brooklyn Zinefest.

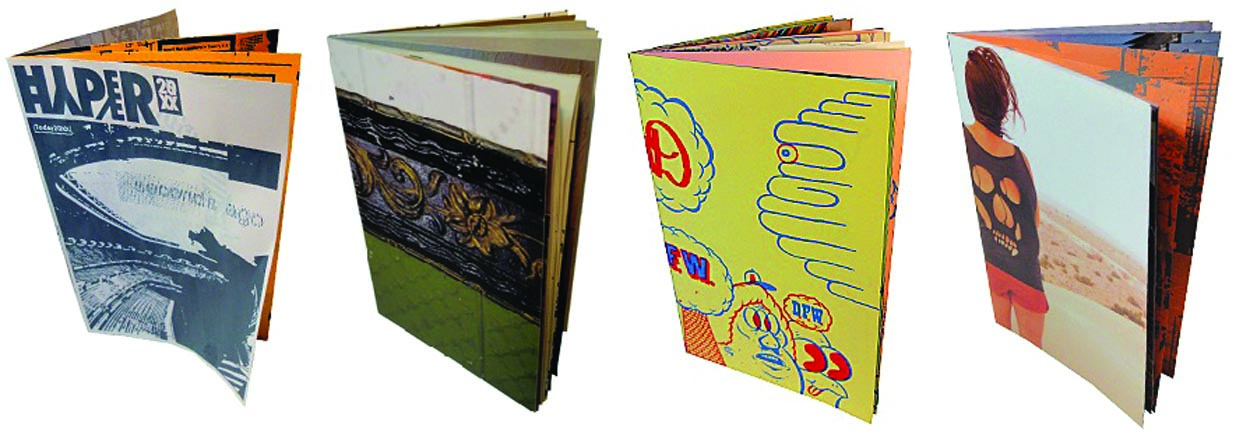

For those unfamiliar, a “zine” is, according the Urban Dictionary entry, “a cheaply-made, cheaply-priced publication, often in black and white, which is mass-produced via photocopier and bound with staples.” Yet the zine’s stripped-down production method is simply a by-product of its essential nature, namely, that it is weird.

In fact, some of the more popular zines have graduated from the photocopy format and, with support from fans, collaborators and advertisers, produce glossy magazines, publish books and run slick websites. One such example is FOUND, an operation that posts found items (letters, homework, ticket stubs, doodles, etc.) on their website, publishes them in a yearly zine and occasionally produces a book.

FOUND’s success is partly due to the fact that its content can be placed in an established artistic tradition; the Dadaists took “ready-made” artifacts (like a urinal) and artistically recontextualized them. FOUND’s context of anonymity makes us look at love letters and parking tickets as a story rather than our story, and in doing so we react differently, and because we think of these objects as real, we value them differently as well.

Most of the publications at the Brooklyn Zinefest—and this is true of zines in general—are artistically oriented. With no editor but the self, self-publication is the playground of poetry, short fiction, photography and drawing. This can result in uninhibited, experimental, fascinating work. It can also result in the kind of work that no one else would publish: bad work.

The boatload of available crap, however, cannot be a criticism of the zine format. One subscribes to the New Yorker because one trusts its editors to provide a certain kind of content. One subscribes to the National Enquirer for the same reason. The only difference between a crappy zine and a crappy magazine is that fewer people read the former.

Included among the 60 plus zines at the Brooklyn Zinefest were such titles as “Discomfort” (“abrasive counter-culture materials… memoirs, poetry, harsh imagery, vegan recipes …”), “I Love Bad Movies” (“essays and illustrations about great-bad films”), and “Deafula” (“a humorous, straightforward and informative resource for hearing folks on how to be a better ally for deaf people.”)

Many magazines would publish an article on these kinds of subjects, but it is the zine’s perpetual commitment to the weird that makes it a special and invaluable resource. Perhaps one can find a humorous essay about interaction with deaf people in Harper’s Bazaar. Perhaps one can look up a vegan recipe online. But zines offer a sustained passion for esoterica, and one cannot find that anywhere else.

Matt Carman (I Love Bad Movies, Brooklyn Zine Fest 2012) • May 2, 2012 at 11:49 am

To clarify, Brooklyn Zine Fest 2012 exhibitor Pendulous Breasts Quarterly features writers for national publications including The New Yorker, and exhibitor Chris Piascik’s work on Mayer Hawthorne’s album cover was included in Rolling Stone’s review. Those publications would, and do, publish BZF tablers’ work.

Additionally, Ayun Halliday is a regular columnist for Bust, writers of The Daily Show contribute to I Love Bad Movies, and Good Day New York devoted a six minute segment to Slice Harvester, among many other collaborations between zine creators and traditional media.

Writers and artists publish their own work because of the creative freedom, control, and dedication involved. Many of them also work in traditional media. Some have non-creative jobs and create zines as their own personal outlet. Whatever the case, the large majority of zine makers found at this year’s Brooklyn Zine Fest would be right at home in the pages of The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, or Brother Mouzone’s beloved Harper’s.