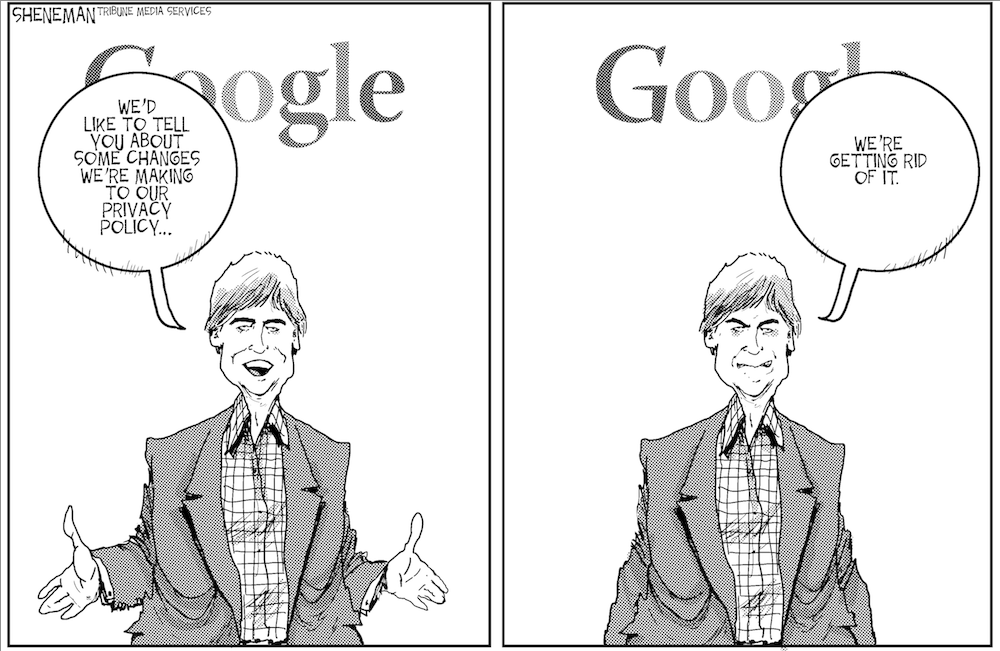

Do They Know too Much? A Look into Google’s New Policies

February 22, 2012

In the world of tech giants, information is power. It doesn’t take much for the public to label a company as ‘evil.’ Fox News consistently receives that branding for their conservative perspective on news reports. Groupon has been described as evil for destroying value and bottle-necking cash flow to smaller businessses.

Massive companies like Verizon, AT&T and Apple are always on the fence between being classified as good or evil. But multi-billion dollar company, Google, has managed to stay on consumers’ good side regardless of the occasional negative headline. But what many consumers seem to regularly overlook is that Google knows everything about them: their habits, their preferences, their friends and their darkest secrets.

Web users have come to embrace Google’s plethora of services such as YouTube, Gmail, devices running the Android operating system, Google Documents, and of course, Google Search. But even Google has to make money, and many users don’t stop to consider just how it turns a profit.

Google makes money primarily through advertising. But buying ads on Google is markedly different from other outlets. On Google, advertisers know exactly who they’re targeting. When a consumer uses a Google product, the person’s searches, documents, Google Voice conversations, pictures, emails, history and information from Google’s over 50 other services are stored and read. Google then utilizes the user’s information, targeting them with tailored advertising.

But a little advertising never hurt anyone. Logan Weir, Fordham College of Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’12 doesn’t mind the invasion of privacy. “Ads are fine because I’m getting free services in exchange. It’s the natural evolution of marketing. It has moved from targeting a group, to targeting the individual,” Weir said.

But consider the situation where lower income females are innundated with write-ups on the latest reality TV shows rather than valuable current news. Are they less likely to remain up-to-date and involved on the issues that actually affect their lives?

Gabriella Solano, FCLC ’12, was a bit more concerned with Google’s informational power. “I understand that it makes sense from a business’s point of view, but I find the whole thing to be a little on the creepy side. It just proves that whatever you do on the Internet is never really private.”

If a user’s information is being used, many feel they should be notified and allowed a degree of control. Often the person using a Google product has no idea what they’ve signed up for. Even Google’s user-friendly revised privacy policy and terms of use are very lengthy and drowned in vague jargon. For example, the policy “…includes a right for Google to make such content available to other companies, organizations or individuals with whom Google has relationships for the provision of syndicated services, and to use such content in connection with the provision of those services.”

Although Google can still seem to do no evil, having one’s information gathered can be dangerous. In addition to advertising, a user’s data profile can be used as criminal evidence and for sterotyping. As a result of search terms, web history, conversation topics and more, a person might be grouped into stereotypes that affect their credit score, insurance rates, employment and more.

Google has made its relative innocence evident through its revised privacy policy, but it is frightening to consider what is possible. Popular retailer, Target, recently revealed that it can tell whether a customer is pregnant and even predict their due date using only the person’s purchase history. In the future, users of Google’s free services and all Internet users in general should become more careful and more critical of their Web surfing habits. At present, Google is facing a potential lawsuit in response to the discovery that users’ privacy settings were being circumvented on the Safari Web browser. And the recent iPhone scandal, in which Apple was secretly tracking the location of its users, has proved that smart phones are also extremely viable sources for gathering unauthorized personal data.

Marko Konte, FCLC ’12, commented, “I have no problem with ads for the time being. What bothers me is that this is just another step toward some uncertain future.” And though the future may be uncertain, consumers can expect more violations of privacy and more ethical dilemas to come. Because for giant and seemingly all-knowing companies, information will continue to reign supreme.