Do not take your jeans for granted; what is now an everyday staple for women was once a serious scandal. The story of women’s pants is also the story of free press and its ability to challenge the status quo, with one activist at its center. With today’s media landscape facing threats to journalistic independence, it is worth revisiting the history that proves why we need it.

In the mid-19th century, American newspaper editor Amelia Bloomer pushed for trousers as a practical alternative to restrictive dresses. As editor of The Lily, the first newspaper in the United States edited by and for women, she wrote about health, education and temperance — but it was her decision to promote the “Bloomer costume” that captured national attention and sparked fierce public debate.

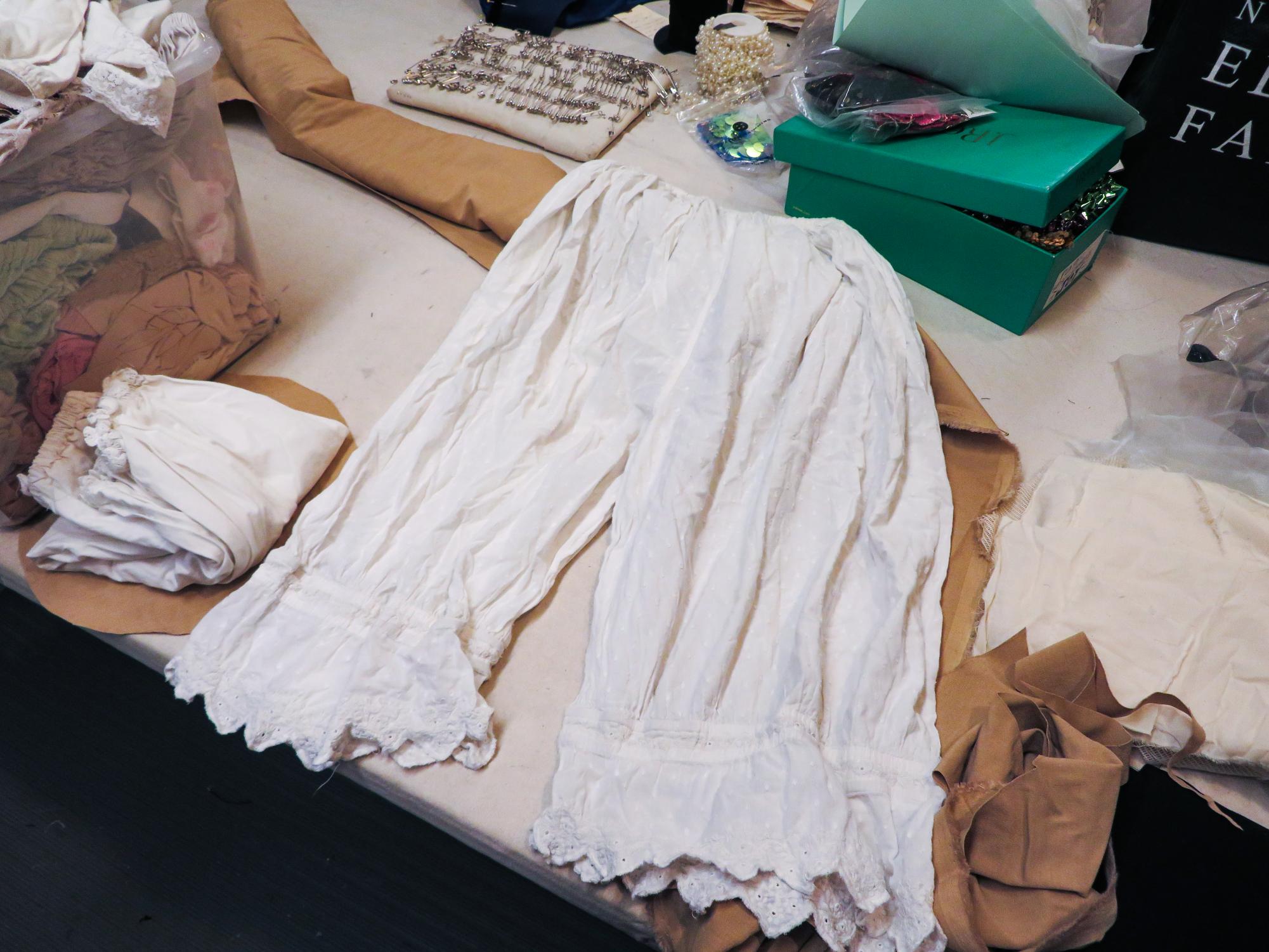

In Bloomer’s time, women were bound not just by corsets and layers of fabric, but by a domestic sphere that left little room for independence. Clothes reinforced the boundaries. Wide skirts knocked against furniture and hemmed women in at home. Long trains dragged through dirt and made walking through the street nearly impossible without assistance. A garment was not only a garment, but a daily reminder of the limitations placed on women’s bodies, and by extension, their lives.

The idea of loose trousers worn under a shortened skirt had already been circulating among women’s rights activists, but it was Bloomer who gave it momentum, and more importantly, words.

As Bloomer wrote in the September 1851 issue of The Lily, “The new costume appeals, however, to our common sense — that back-bone of the mind.” She argued that trousers offered women practical freedom by “redeeming woman from bondage of dress,” which quickly linked clothing reform to a larger emancipation movement, for both the physical and intellectual lives of women.

Bloomer did not invent the outfit that would come to bear her name. The idea of loose trousers worn under a shortened skirt had already been circulating among women’s rights activists, but it was Bloomer who gave it momentum, and more importantly, words. When a male editor suggested that women could solve fashion woes with “Turkish pantaloons,” he thought he had solved the problem — and that they would thank him for it. But rather than being placated, the righteous anger in Bloomer was only fueled; she made it clear in her paper that clothing alone would not cut it.

Reform meant little if women had few rights to call their own. Without those words, the outfit might have remained an obscure experiment. In the press, it became impossible to ignore.

“The Lily was revolutionary because it gave women a space to speak in their own voices at a time when the overwhelming majority of newspapers and journals were edited by and for men.” Amy Aronson, Journalism Professor

Like The Lily, independent outlets today continue to challenge dominant narratives.

“The Lily was revolutionary because it gave women a space to speak in their own voices at a time when the overwhelming majority of newspapers and journals were edited by and for men,” Fordham journalism professor Amy Aronson, who has extensively studied the history of women’s magazines, said.

“That same spirit lives on today in smaller, independent, and digital outlets — especially those led by women and marginalized communities — which publish stories and perspectives mainstream media often overlook,” Aronson said.

Once published, the “Bloomer costume” became a cultural flashpoint. Satirical cartoons appeared in newspapers, lampooning women with swollen pantaloons and cropped skirts. Preachers railed against the “unnaturalness” of women stepping into trousers. It clearly became a threat to the male sphere.

To many, the outfit was laughable, even dangerous. But the ridicule only confirmed what Bloomer herself must have known: Words in print could transform a piece of clothing into a political statement. By attaching language to the movement, she turned fashion into an argument about freedom — to move, to work and to live outside the rigid confines of the domestic sphere.

Just like in Bloomer’s story, using visibility as resistance is still a vital tool in modern journalism.

“Today, women journalists and creators use their platforms in similar ways — to confront the policing of women’s appearance, voice, and behavior,” Aronson said. “Think of sports reporters calling out sexist coverage, or foreign correspondents documenting gendered violence, or commentators challenging online harassment and double standards. Like Bloomer, they use visibility itself as a form of resistance — turning what society tries to regulate into a statement of agency.”

Bloomer’s story is a reminder of how the press has been a long-standing catalyst for change.

“That dynamic continues today: journalists such as Maria Ressa, Christiane Amanpour, Jane Ferguson, and Nikole Hannah-Jones show that media platforms can still shape how societies understand justice, equality, and gender,” Aronson said.

The “Bloomer costume” is undoubtedly a landmark piece in fashion history, but it was the role of a woman journalist who brought it to life. Bloomer’s independence is a leading example for a media landscape strained by financial pressures and corporate priority, much like the current industry.

“They may not have the biggest budgets, but they often have the clearest sense of purpose,” Aronson said. “Bloomer published The Lily from her home, often funding it herself and relying on a network of reform-minded contributors. That independence gave her freedom to cover ideas that mainstream editors dismissed as trivial or dangerous.”

Today, when large organizations face layoffs and shrinking budgets, smaller publications and newsrooms are capable of carrying forward Bloomer’s mission.

“Her legacy endures in every journalist who treats independence as a form of integrity,” Aronson said.

To thank Bloomer is not only to thank her for trousers, but to thank her for proving that a woman’s words are truly and exceedingly powerful. This is something worth remembering as the future of journalism faces its own constraints.