Fall’s Freewheelinest Flick

May 29, 2011

Published: November 8, 2007

Just because “I’m Not There” is a Bob Dylan movie, that doesn’t mean you should see it stoned. For one, it’s not a Bob Dylan movie in the traditional sense: not a biography, not a narration, not a live performance, not even a mention of the name “Bob Dylan.” But mostly, you’ll want to remember the film’s every detail, because come Nov. 21, it will undoubtedly be the coolest conversation piece on campus.

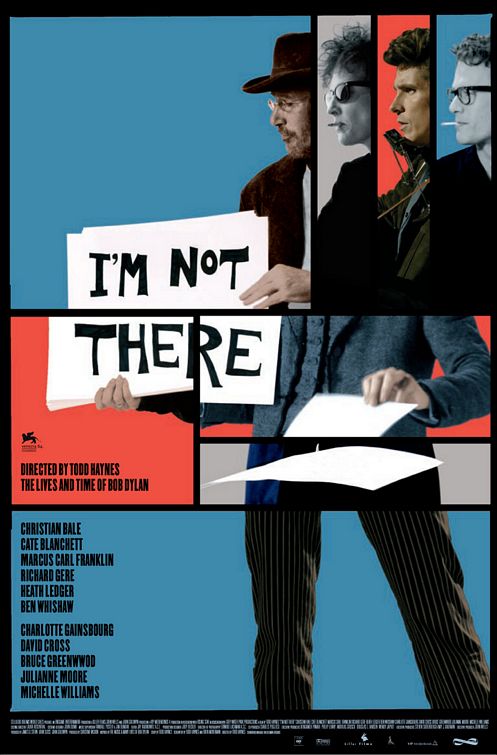

The film, directed and co-written by Todd Haynes, reincarnates the personalities of Bob Dylan in six diverse characters: a 13-year-old African-American boy, as “Guthry” (Marcus Carl Franklin); Robbie (Heath Ledger) the womanizer, who tours incessantly; the famed folk-star Jack (Christian Bale) who becomes an evangelist; the young rebellious poet, Arthur (Ben Whishaw); the Western outlaw, Billy (Richard Gere); and last but not least, Jude Quinn, the electric, troubled, mysterious, chain-smoking Dylan (played by Cate Blanchett, who steals the show by far).

“I had this whole sort of physical urge to respond to Bob Dylan’s life and work,” Haynes said of his film, after its second screening at the New York Film Festival in October. “This came in the same package as the desire to explode him into other people, but it was tricky—we had to ask, is this plausible?” Seven years in the making, the biopic is the first non-documentary film to have ever scored the rights to Dylan’s music and story, and takes its title from the obscure Dylan bootleg track of the same name.

Haynes began meeting with Dylan’s son, Jesse, in the summer of 2000 to discuss ideas for the film. Both Jesse and Bob were intrigued; the collection of American archetypes reminded Jesse of the work of Allen Ginsberg.

As so eloquently put by Robert Sullivan for The New York Times, for a Bob Dylan movie to make complete sense would make no sense (and Dylan would surely agree). Haynes’ film embraces this concept, serving as more of a collage or montage of six stories than a traditional biographical film.

The story does provide some interesting truths about Dylan, showing the chaos of his confrontations with journalists and fans, and illustrating the cold response he received from long-time fans after sharpening his rebellious edge and abandoning his folky protest songs. The film also hones in on the fine line that lies between his creative process and his personal life. Dylan lived through rough times and faced intense pressure—it’s amazing that his body kept up with the combination of the intensity of his work and his own destructive vices. Haynes wanted his audience to understand this. In one scene, Blanchett’s Dylan asks, “Who needs sleep? Sleep is for dreamers. I haven’t slept in 30 days.”

On the other hand, there’s a great deal of fiction in the film: we know that Dylan was neither a young black boy in his youth, nor was he a woman in his electric years. We’re in the on the jokes, making the experience of seeing the film even cooler.

The film’s tendency to jump around from character to character may confuse some viewers, but the mixed order of scenes is meant to resemble the spontaneity of a Dylan song. Some things do go unexplained, and may be hard to understand without prior knowledge of Dylan’s life. Most people, though, will pick up on the spontaneous drop-ins from legends of the 1960s like The Beatles and Allen Ginsberg. Haynes used the 1960s to constrain the film’s content; he also wanted the film to appear as though it was from the 1960s, and studied 1960s cinema and styles of directing for the film.

Of course, the great questions stand: has Dylan seen the movie, and how does he like it? The answers to these questions are, apparently, blowin’ in the wind: Haynes explained after the screening that a DVD had been sent to Dylan, but he had received no feedback. “To a certain degree, I think the ‘don’t look back’ theory really applies to him,” Haynes said, “but hopefully he’ll watch it.”

Simply put, this film is brilliant—be there when it hits select theatres this Nov. 21.