For college students, whose brains are typically still developing, the dangers of addiction are constantly present. Thanks to Fordham’s mandatory alcohol awareness training and constant warnings from worried parents, it’s a well-known fact that the use of alcohol and drugs can easily fall into addictive patterns. Addiction isn’t just limited to substance abuse — numerous reports have warned that activities such as playing video games, scrolling on your smartphone and compulsive internet shopping can also become addictive. However, there’s one more emerging technology that should head the list of dangerous addictions: artificial intelligence (AI). As AI becomes increasingly ubiquitous, all users should be cautious of the psychological danger presented by AI.

The obvious danger comes from large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Microsoft’s CoPilot. LLMs are generative AI systems that allow users to prompt and receive answers from chatbots. LLMs are trained on large databases of texts, which are processed through algorithms that mimic human language and all of its biases. These algorithms are what enable LLMs to answer user prompts — not through actual thought, but through predictive abilities based on the algorithmic study of human texts.

AI is not just a homework tool — it’s a new form of socialization.

According to a study by Elon University, more than half of American adults have used an LLM, with 34% of them reporting daily use of the tool. LLM usage by teenagers is more common; a study by Common Sense Media reported that 52% of teenagers regularly use an “AI companion.” For 33% of those teenagers, the LLMs provide a form of social interaction. AI is not just a homework tool — it’s a new form of socialization.

It’s easy to see why this phenomenon emerges. Chatbots are easily accessible: they’re usually available for free, and they’re found via websites rather than applications you have to separately download. When one is given a tool that claims to provide an answer to any question, it’s not surprising that users turn to it with questions about the human experience.

The dangers of using AI for companionship or therapeutic relief have been revealed in a few landmark cases. In late August, a family sued OpenAI and its founder, Sam Altman, in the wrongful death case of their teenage son. According to a New York Times report, the family’s suit against OpenAI claims that ChatGPT intentionally encourages psychological dependence and does not have enough safeguards in place to prevent the chatbot from providing life-threatening advice.

Recently, Futurism — the publication that previously investigated Sports Illustrated’s AI writers — released an article on the effects of ChatGPT on various divorced and separated couples. The common thread between all the examples was that, for one of the spouses in the bereaved partnerships, a chatbot served as an echo chamber that validated their emotions and provided no pushback on their perspectives. The use of chatbots was found to inhibit couples’ therapy sessions or even simple constructive conversations, causing complex and often sour litigation processes for legal separation.

This summer, The New York Times published the story of Eugene Torres, an accountant who began using ChatGPT for help with his job. He ended up asking questions about simulation theory, the idea that the world is an illusion run by a higher being. The series of dialogues with the chatbot encouraged Torres into a spiral of delusion, as he thought he was suddenly clued into the falsity of reality by ChatGPT. The program did nothing to curb his descent into conspiracy and paranoia.

All of these distressing examples reveal the key danger behind LLMs: Though they mimic human speech, they do not even remotely understand human thought. They are echo chambers of the worst kind, because they manage to convince the user — through superficially original speech — that they are legitimate interlocutors. This quality of AI is understandably addictive, as explored by a study published this year by the Asian Journal of Psychiatry.

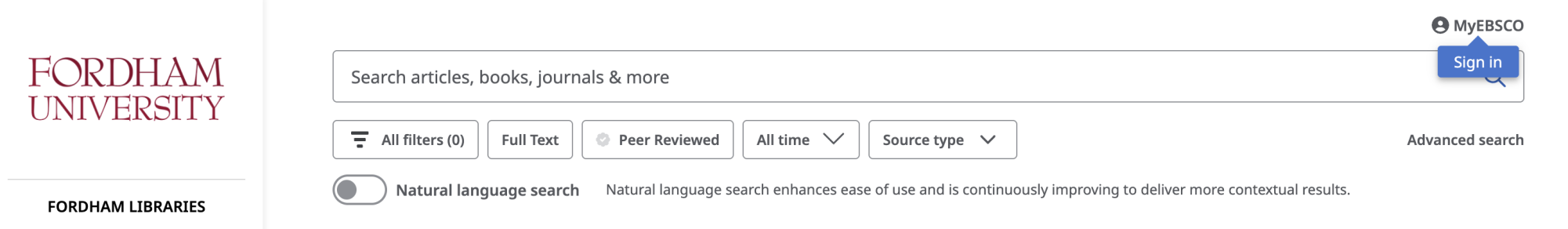

As someone who is firmly against AI and has proudly never used a chatbot for any reason, I read those stories with horror and fear. However, as much as I am against AI, I have unavoidably used it many times — without my consent. AI is now built into every platform, from Google’s Gemini to Microsoft’s CoPilot. Even Fordham Libraries’ third-party database management system, EBSCO, offers “natural language search,” a form of AI that parses a user’s query so that “more contextual clues and users’ intent can be honored,” according to EBSCO’s website.

In comparison to horror stories about chatbots, there are many innocuous forms of AI available for daily use. It might seem harmless to have Zoom’s AI summarize a meeting, or easier for Spotify’s AI DJ to pick your daily soundtrack. However, I argue that these kinds of AI are akin to a gateway drug, which leads us to complete dependence on the technology. Abstinence from AI should be encouraged whenever possible in order to evade the development of addictive behaviors.

I’m not trying to be sanctimonious or hysterical. AI does, in a lot of cases, make people’s lives easier. The question I’d like to raise is whether or not that ease is worth the possible risks. Even with small tasks, surrendering your competence to the work of AI is slowly destructive. If AI starts taking your meeting notes, why would you ever take notes yourself again? If AI autocorrects your essays every time, how will you ever change your composition style for the better? If AI suggests your music, why would you ever go looking for a new genre yourself?

AI makes life easier because it skips the creative processes we dread. You don’t need to think of an idea, you can just prompt ChatGPT. You don’t need to search a website yourself, you only have to ask the customer service chatbot to locate something for you. You can summarize a book without even opening the cover, and you can draw a picture without putting pencil to paper.

Even with small tasks, surrendering your competence to the work of AI is slowly destructive.

However, these creative practices have been part of human life for years. When you do them yourself, you are at risk of making a mistake — but that’s how you learn, and make things easier for yourself next time. You remember a meeting because you went through the process of taking notes and stimulated your brain. You find new research possibilities by going through texts you might not use, but might have something helpful in their footnotes.

Once you hand over your grunt work to AI, you’ll likely never want to do that work yourself again. That’s an appealing idea, but dangerous when scrutinized. After all, the aforementioned Torres started using AI for help with his office tasks, and ended up in a ChatGPT-induced spiral. While that’s not going to happen to everyone, I argue that the possible risks of AI should inform every single use of the technology, even its innocuous forms that are built into websites and applications.

There’s a litany of arguments against the excessive use of AI, which cite its frequent plagiarism, implicit racial and gender-based linguistic bias, and harmful impact on the environment. Its addictive nature, and the degenerative mental effects that can be caused by over-dependence, should be added to the list of diatribes against the technology. When you’re thinking about opening ChatGPT, maybe the lesson taught by your old D.A.R.E. program officials should apply — just say no, it’s more dangerous than it’s worth.