Faculty, graduate students and many other members of the Fordham community gathered in the Flom Auditorium of Walsh Library on Sept. 18 to attend the first McGinley lecture of the 2025-26 academic year: “The Ethics of Meritocracy: A Theological Assessment.”

Jonathan Crystal, vice provost for academic affairs, moderated the event, which marked the most recent iteration of the McGinley lecture series, a longstanding Fordham tradition since the 1980s.

The series was created by the late Cardinal and Jesuit priest Avery Dulles when he became the first holder of the Lawrence J. McGinley chair in Religion and Society in 1988.

In accordance with the original purpose of the lectures — discussing the complex interplays between religion, politics and culture in pluralistic American society — the event evaluated the ethics of a meritocratic system in the context of contemporary American capitalism through a theological lens.

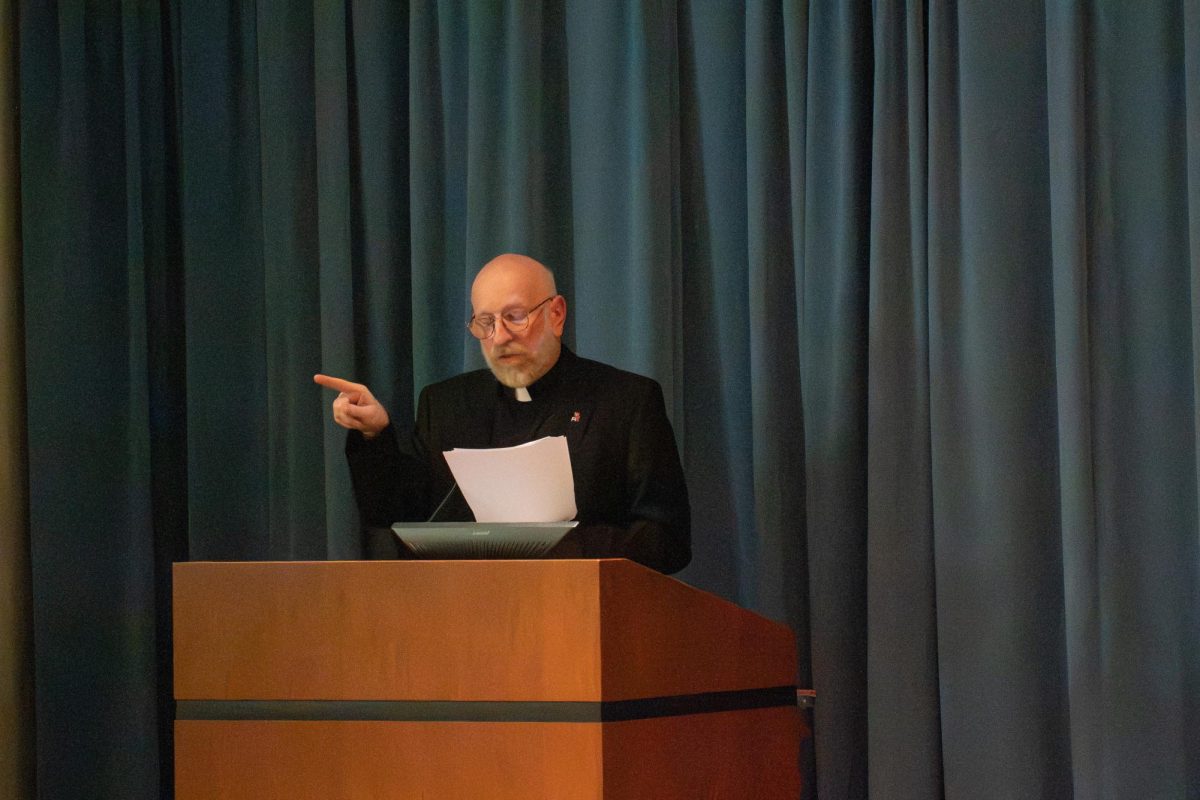

Thomas Massaro, Jesuit priest and professor of moral theology, is the current McGinley chair. He delivered the lecture exactly a year after his inauguration as chairholder alongside Megan Bogia, associate director for academic programs and strategic initiatives of the Center for Ethics Education.

In accordance with the original purpose of the lectures — discussing the complex interplays between religion, politics and culture in pluralistic American society — the event evaluated the ethics of a meritocratic system in the context of contemporary American capitalism through a theological lens.

Massaro began his lecture with his definition of meritocracy.

“Today’s topic concerns one of the central organizing principles of our society — namely, how we distribute to one another the wide range of social goods that define our lives, including material wealth and income, but also less tangible goods, such as social status, personal recognition and opportunities for advancement,” Massaro said.

Massaro further described meritocracy as a system that perpetuates a divide between the “winners” and the “losers.” He cited the arguments of philosophers and sociologists like Michael Young and Michael Sandel, both authors of books on the notion of meritocracy.

“‘By justifying a narrow measure of merit and bestowing outsized rewards on people possessing only certain skills, a meritocratic system tends to foster great hubris in the winners and extreme humiliation among the losers,’” Massaro said, quoting Michael Sandel’s book “The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?”

Massaro expanded on this idea, explaining how winners’ egos inflate as they bathe in the benefits of the “diploma divide” and losers feel the “brunt of harsh, moral judgmentalism.”

His respondent, Bogia, countered that it can be fair for winners to feel hubris if meritocracy lived up to its promises of equal opportunity.

“We all have a solemn obligation to resist the mechanisms that exclude and stigmatize our brothers and sisters, and which are inconsistent with the values of human compassion, fairness, inclusivity and neighbor regard,” Thomas Massaro, Jesuit priest, Professor of Moral Theology and Current McGinley Chair

“The ideal of meritocracy survives this reality if it limits its promise to input. That is, to equal opportunity, not equal outcomes,” Bogia said.

Bogia concurred that meritocracy can — and will — continue to exist within American society.

“Liberal advocacy for a view such as this one underscores that meritocracy need not be our primary organizing principle, economically or culturally, without having to abandon the premise entirely,” Bogia said.

Massaro emphasized individual moral responsibility to reform systems that violate human dignity.

“We all have a solemn obligation to resist the mechanisms that exclude and stigmatize our brothers and sisters, and which are inconsistent with the values of human compassion, fairness, inclusivity and neighbor regard,” Massaro said.

When asked about the relevance of understanding meritocracy in the modern day, Massaro noted that it is extremely important as income inequality becomes more severe and pervasive.

“The rich are getting richer (and) the poor are getting poorer,” Massaro said. “So this topic, for me, captures the moral imperative.”

Massaro also believes it is crucial for younger generations, especially college students facing the hurdles of the job market, to critically reflect on the practical reality of meritocracy in America will affect their futures.

“Opportunities are more closely attached to credentials. In my time, you could make up for the lack of a master’s degree by doing something else or having some skill that you could demonstrate,” Massaro said. “I think that’s less likely now, so college admissions become more prioritized, or heightened. So you’re going to have to fight.”

The proceedings ended in a 15-minute question-and-answer session, where Massaro and Bogia answered questions from the audience about topics like meritocracy in college admissions, AI and religious life.

To close the lecture, Massaro highlighted the question he believes his audience should be asking themselves after they leave the auditorium doors.

“In whom are we willing to invest public resources, private resources (and) opportunities? Yeah, we can’t guarantee outcomes; we can’t even guarantee the quality of opportunity. It’s a complex world; there’s a lot of injustice out there, and the starting points are staggered,” Massaro said. “But if we’re willing to invest in people, both monetarily and (with) advice, or even a good kindly counselor (that) can steer you in the right direction. That counts.”

The information for the next McGinley lecture of the 2025-26 academic year has yet to be announced.