This year marks the 50th anniversary of the fall of Sài Gòn during the Vietnam War. While it is more often discussed in the United States as it relates to American politics, this war was pivotal in Vietnamese history. The nonprofit organization Vietnamese Boat People (VBP) is working to immortalize the journeys of Vietnamese immigrants who gave up their lives to seek refuge in other countries.

The term “Vietnamese boat people” is used to describe the almost two million Vietnamese immigrants who fled Vietnam between 1975 and 1992, enduring harrowing journeys by boat, plane and foot to escape Northern Vietnamese forces and communist rule. VBP aims to highlight their “hope and resilience” in the face of danger.

Starting as a podcast in 2018, the nonprofit organization Vietnamese Boat People has evolved into a multimedia platform dedicated to empowering individuals across the Vietnamese diaspora. As “Our Journeys” exhibition curator Sophia Ma explained, VBP works to capture individual narratives of “Vietnamese immigrants who left their homes in search of a better future,” which “embod(ies) a universal part of the American experience.”

“(‘Our Journeys’) is developed around the core concept that a story passed down is a gift — something given to another with intention and without obligation.” VBD’s Official Website

Ma and Tracey Nguyễn Mang, founder of VBP, compiled artifacts and stories submitted by Vietnamese immigrants, descendants of immigrants and soldiers to create the traveling exhibition entitled “Our Journeys: 50 Years After the Fall.”

“(‘Our Journeys’) is developed around the core concept that a story passed down is a gift — something given to another with intention and without obligation,” VBP’s official website states about the goal of their exhibition. “For a community whose stories have often been told by others, this traveling exhibit seeks to forefront the Vietnamese diaspora as narrators of our own story and as it travels, to educate broader audiences on the Vietnamese diaspora experience.”

By giving them a space to document their individual histories, VBP reinforces the complexity and individuality of Vietnamese people, a truth often neglected in the retelling of Vietnamese history.

“Hearing how our grandparents overcame war, migration, or discrimination can help us face challenges with greater perspective and hope,” Ma said. “(We) can transform (cultural) practices from mere rituals into meaningful parts of our identities … During this fraught moment of chaos, being able to close cultural gaps brings the potential for us to recenter our shared humanity.”

Mang detailed her own family’s immigration in the preface of the “Our Journeys” anthology book, which accompanies and expounds upon the content of the exhibition. Mang describes leaving her home in 1981 with her mother and sisters, just before her fourth birthday. Their goal was to reunite with Mang’s father and brothers, but Mang “had no memories of them.” At the forefront of her mind was “only the life (they) were leaving behind.”

“The shadows of war, escape, and displacement shaped our family in profound, lasting ways,” Mang wrote. “On the days we saw our mother, she shared beautiful moments of her upbringing in Vietnam. But the remembrances of war and a fallen country quickly overshadowed those memories. She recounted … a past filled with hardship and loss. I didn’t want to listen; the stories made me incredibly sad, and I found it easier to run away from them.”

“What to me is forced departure is perhaps to my parents and family a narrative of choice. Even when the country became unrecognizable for my parents, they would still say they ‘chose’ to leave.” Yen Vu, VBP Podcast Guest

When Mang became a mother herself, she found new interest and appreciation in the layers of her family’s story of resilience. Taking the time to engage with her personal history, she “began to reconcile with the sacrifices and trauma” that marked her family’s journey. This self-realization was her exigence for founding VBP and creating the exhibition: The collection’s main purpose was ultimately to “illuminate the strength, complexity, and humanity of the Vietnamese diaspora.”

The individual complexity of Vietnamese immigration experiences is highlighted throughout the exhibition. A banner in the exhibition displayed a quote from VBP podcast guest Yen Vu, which called attention to how perspectives on traumatic migration often contrast between generations in immigrant families.

“What to me is forced departure is perhaps to my parents and family a narrative of choice. Even when the country became unrecognizable for my parents, they would still say they ‘chose’ to leave,” Vu said. “I wonder if they have mythicized this narrative of choice as a way to remember things differently.”

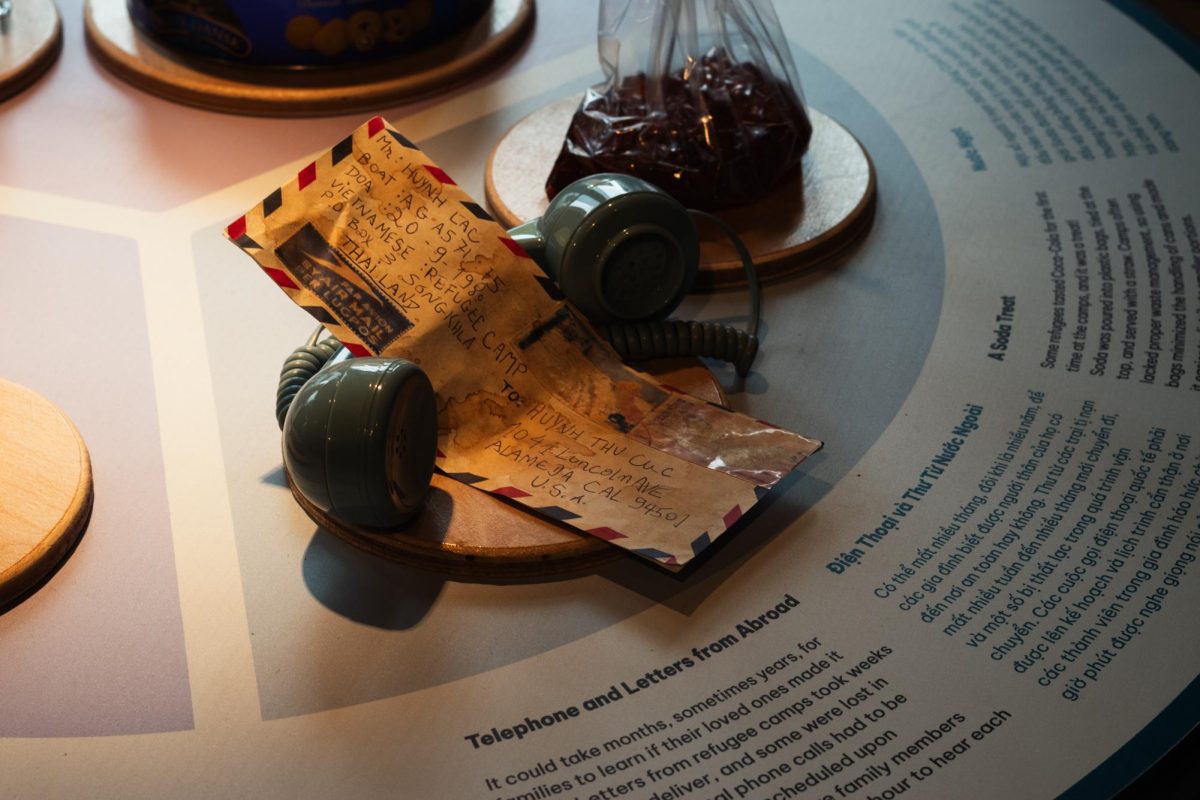

The practice of shaping one’s memory is a point of interest in “Our Journeys.” Further exploring this, the exhibit displayed images of personal artifacts along a wall, corresponding to blurbs that explained the significance of each to their beholders.

For example, Peter Nên Hoàng chose to submit a photograph of his martial arts training record. This record was among the few documents Hoàng prioritized bringing from home. According to the accompanying text, the training record “symbolized his identity, discipline, and pride in personal achievement.”

The exhibit showcased a few other personally significant artifacts with individual stories — the novels that hid Phước Tấn Nguyên’s escape plan, a comb “carved from the metal of a fallen plane” by Phuong Lien Palafox’s father for his wife, Cindy Nguyen’s “baby identity card” and Naoko Tsunada’s birth certificate which revealed her given Vietnamese name, Mỹ Thị Bùi.

The submissions of Hoàng and others reveal that, for Vietnamese boat people, preserving one’s personal identifiers was equally as significant as survival. Hoàng’s martial arts training record was not vital to his survival of the journey, but to the continuation of his life.

“The fight for migration justice asks us to recognize the dignity of all persons and to stand with immigrants, in solidarity, as we work to achieve a more just, democratic society.” Dr. Carey Kasten, Director of Fordham’s Initiative on Migrants, Migration and Human Dignity

The exhibition addressed not just Vietnamese immigrants, but all individuals across their audience. The collection emphasizes feeling connected to oneself and one’s homeland, revealing “how individuals reconnect with the past, reclaim their narratives, and find belonging in the present.” Rather than only referring to Vietnamese boat people, the didactics urge awareness of the diverse histories of all.

Dr. Carey Kasten, director of Fordham’s Initiative on Migrants, Migration and Human Dignity, also believes in the importance of history. Kasten pointed out that most non-indigenous Americans are descended from immigrants, urging that “we need to remember what it was like for them, the opportunities that were afforded to them and the ways they struggled.”

“I believe that working toward migration justice is key to our identity at Fordham,” Kasten said. “The fight for migration justice asks us to recognize the dignity of all persons and to stand with immigrants, in solidarity, as we work to achieve a more just, democratic society.”

Kasten stated the significance of community where there might be a divide, advising that “staying silo-ed and silenced is not the answer.” She also explained the role of art in bringing people together to celebrate diversity by helping us “process collective social trauma.”

The exhibition also addressed the specific experience of immigrant children, who were “caught between cultures and searching for a place to belong.”

Eva Lee, Fordham College at Lincoln Center ’27, is the daughter of Chinese immigrants and serves as president of the Immigration Advocacy Coalition on campus. Lee described her experience growing up with distinct Chinese and American cultures as “very disorienting.” Lee found her Fordham education in political science and Asian American studies to be very eye-opening on Asian American identity. She stressed the importance of learning “to create a more fair and complete picture of one’s own history.”

“Asian American stories … they’re so rich, and they’re also so homogenized,” Lee said. “If you live in a vacuum, very quickly you can fall victim to divisive politics and to stereotyping other people, and even stereotyping yourself.”

VBP’s exhibition details stories from a variety of Vietnamese immigrants, emphasizing their individuality. This effort combats stereotyping and dilution of Vietnamese history.

“Taking the initiative to learn about Vietnamese American history has taught me that … young people today are still deeply, deeply impacted,” Lee said. “People’s lives are still getting uprooted … because of certain political decisions. So it is so important to take a step back (and) look at these exhibitions and museums.”

To reconcile being overwhelmed by societal and emotional pressures or feeling lonely, Ma urges marginalized students to “allow (themselves) to feel these emotions.”

While Lee stressed the importance of immersing oneself in diverse histories, she also pointed out that there is a “fine line and difference between … advocating for yourself … and also feeling the burden of having to educate everyone around you.”

“There is a sort of unspoken responsibility … placed among marginalized people in America of having to explain themselves, having to explain why they belong,” Lee said.

To reconcile being overwhelmed by societal and emotional pressures or feeling lonely, Ma urges marginalized students to “allow (themselves) to feel these emotions.”

“Remind yourself why you made this journey,” Ma said. “Your experience, struggles, and successes are part of a powerful story that no one else can tell.”

This exhibition debuts in unprecedented times, as topics of American discourse are being actively censored and immigrants across the states are being jailed before they can explain why they are in the country.

At the beginning of Trump’s second term, The New York Times published an article listing the hundreds of terms that were ordered to be limited or avoided by the federal government as the Trump administration seeks to purge “woke” legislation. Among these terms were “multicultural,” “immigrants” and “community diversity.”

The current administration is working to depict a singular, homogenized picture of America in which immigration directly corresponds with an increase in crime, among other social problems.

More recently, The Washington Post reported that an unidentified national park was ordered to remove signs and exhibits related to slavery.

“The removals were in line with President Donald Trump’s March executive order directing the Interior Department to eliminate information that reflects a ‘corrosive ideology’ that disparages historic Americans,” The Washington Post reported on Sept. 15.

But how do we define a “historic American”? Evidently, the current administration is working to depict a singular, homogenized picture of America in which immigration directly corresponds with an increase in crime, among other social problems.

The White House official website quoted President Trump in a “Fact Sheet” on his executive order to increase law enforcement in Washington, D.C. to “crack down on crime” in the capital: “Just like I took care of the Border, where you had ZERO Illegals coming across last month … I will take care of our cherished Capital, and we will make it, truly, GREAT AGAIN!”

Between unconstitutional deportation policies and terminating Diversity, Equity and Inclusion-related offices, the Trump administration could not have a clearer goal: to sanitize the country’s history of multiculturalism and immigration, two key building blocks of the American foundation.

The current political hailstorm makes VBP’s exhibition even more significant, as they urge their audience to “honor (immigrant) journeys … and reflect on the enduring strength of the human spirit.” Unless one is indigenous — another term now avoided by the federal government — Americans are all descendants of immigrants, a fact that should unify the country.

“Our journeys of migration, spanning continents and generations, are woven into the shared human experience,” the exhibition concluded. “Stories are our heirlooms, gaining deeper meaning with each retelling.”

VBP’s exhibition significantly reflects how learning about personal histories greatly contributes to cultivating diverse communities. Even through the “isolation and the quiet struggle” of Vietnamese boat people, they persevere through hardship and are able to connect through their resilience “to rebuild … Vietnamese communities.”

Many have expressed the importance of community building, whether that be in a new classroom or a new country. When asked for her advice for immigrant and international students going through hardships, Kasten replied: “Seek out community.”

“It can be hard to open up,” Kasten said. “(But) there are many people on and off campus who want to support immigrants in our communities.”

Lee, as president of the Immigration Advocacy Coalition, made sure to “say specifically that undocumented students have a place at Fordham.”

“I personally don’t think that citizenship matters all that much in regards to one’s humanity, and their human rights, and what they deserve,” Lee said. “I just care that you have shelter and food and the right to happiness … and a right to an education.”

Founder Tracey Nguyễn Mang also wants immigrant and international students to “know that (they) are not alone, even if it feels isolating at times.”

“Many before you have walked similar paths,” Mang said. “Lean into community (and) don’t be afraid to share your story … Hardship can feel overwhelming in the moment, but it shapes strength, empathy, and perspective that will serve you for the rest of your life — even if you can’t see it just yet.”

“Our Journeys,” by Vietnamese Boat People, will be exhibited in Chinatown until Sept. 28. The nonprofit will continue to empower the voices of Vietnamese immigrants, underlining that education on our migrant history is essential to strengthen the shared American voice.