In November 2022, Generative AI became widely available to the public, with the release of OpenAI’s chatbot, ChatGPT. It has been used to create increasingly realistic images, videos and even music.

Spotify, the most popular streaming service globally, has received backlash from users and artists due to the platform’s shady and unethical use of artificial intelligence. Spotify users have been raising alarm bells on Reddit forums for years, calling out the platform for making their own AI “music” and releasing it under fake artist and band names in order to avoid paying real artists royalties for their work.

According to the British news magazine The Week, “reports as far back as 2016 indicate that the platform was allegedly making its own records using the names of people that did not exist. But the recent jumpstart of AI seems to have brought the problem to a heightened level.”

Now that Spotify is creating its own “artists,” the opportunities for smaller musicians are even scarcer.

Spotify has long faced backlash for its insufficient royalty payments, which make it impossible for independent artists to make a living from their work. Now that Spotify is creating its own “artists,” the opportunities for smaller musicians are even scarcer.

For those familiar with the issue, these fake bands and artists are generally easy to identify.

“The artists ‘performing’ the covers — the Highway Outlaws, Waterfront Wranglers, Saltwater Saddles — all fit a certain pattern, with monthly listeners in the hundreds of thousands, zero social media footprint, and some very ChatGPT-sounding bios,” according to Slate Magazine’s Andy Vasoyan.

But to the untrained ear, it can be nearly impossible to discern these recycled tracks from real music. They are generated by scraping actual copyrighted songs from the internet, stealing from independent and established artists alike, resulting in several lawsuits by major labels and taking away the already limited opportunities for exposure available to independent artists.

For independent artists like Viena Aiello, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’25, music is a way of life. The New Jersey-raised singer-songwriter and guitarist started writing songs in elementary school and has been releasing music on streaming services under the name ViVi since 2023. In 2025, she released her first EP “Perennial,” which she recorded and produced from her bedroom.

Exposure is vital for independent artists to find success in the incredibly cut-throat and saturated music industry. In 2015, alternative pop artist Billie Eilish began her rise to fame after she and her brother, Finneas O’Connell, uploaded her song “Ocean Eyes” to the streaming platform Soundcloud. The song quickly went viral, garnering over a million plays on Spotify, and eventually led to Eilish being signed by Darkroom Records.

Ten years later, the rise of generative artificial intelligence has made this kind of success story something independent artists can only dream of.

“AI steals from everyone all the time, and sometimes you can’t even really trace that it is one specific artist. It’s just a bunch of artists mushed together to make something that is not quite new, but at least did not exist before,” Aiello said. “If all of the Spotify recommended playlists are creating their own fake music to recommend to people, there’s no inkling of a chance of exposure for other artists who used to get discovered on Spotify.”

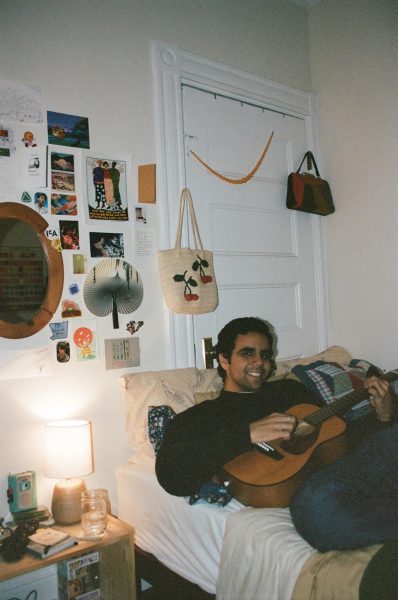

New York City-based artist Gabe Perez has been playing music for over a decade. They graduated from Berklee College of Music with a degree in songwriting and are a guitarist and drummer in addition to producing their own music, including two recently released singles.

“AI music crowding these streaming services only makes it harder for marginalized artists to get their work out there and to be heard.” Gabe Perez, New York City-based artist

Perez has heard the argument that generative AI makes music production more “accessible” to those without experience playing instruments, but thinks “that’s totally the wrong way to look at it.”

“The music industry is so male-dominated, and particularly white male-dominated. AI music crowding these streaming services only makes it harder for marginalized artists to get their work out there and to be heard,” Perez said.

Maco Dacanay, FCLC ’26, is a jazz guitarist originally from Seattle, Washington, who studies under Dr. Matthew Buttermann, director of jazz studies at Fordham University. Dacanay grew up playing guitar and performs jazz around New York City.

“The time when it will be impossible for a layperson to discern between AI music and real-life musicians is coming very quick, and it’s a threat to artists,” Dacanay said. “I would feel more comfortable if Spotify didn’t have AI music on the platform. It would be helpful to know what was made by a real musician and what was made by a robot.”

Currently, there is no mandatory labeling requirement for AI-generated music on streaming platforms.

In 2025, over 200 massively popular artists, including Billie Eilish, Chappell Roan, Doechii, Zayn Malik and even the estates of Frank Sinatra and Bob Marley, signed an open letter organized by the Artists’ Rights Alliance calling to stop the “predatory use” of AI in the music industry. They called on “all AI developers, technology companies, platforms, and digital music services” to “pledge that they will not develop or deploy AI music-generation technology, content or tools that undermine or replace the human artistry of songwriters and artists, or deny us fair compensation for our work.”

“The consequences of major artists endorsing the use of AI fall upon not themselves, but upon those that are advocating against the use.” Maco Dacanay, FCLC ’26

However, not all major artists share this view, such as electronic artist Grimes, who has given anyone permission to use her voice for AI-generated songs, according to the BBC. In a post shared to X, the singer said she would split “50% royalties on any successful AI-generated song that uses (her) voice” and gave permission to use her voice “without penalty.”

“If (people are) using Grimes’ voice (for) AI, and she’s getting the royalties for it … then I would almost say fine for her, except all of the other instrumentation happening in the background is also just being ripped from other musicians, and they’re not getting their royalties. So that feels like a very selfish way to try to co-opt the AI situation … and completely ignore what’s actually going on,” Aiello said.

“The consequences of major artists endorsing the use of AI fall upon not themselves, but upon those that are advocating against the use,” Dacanay said. “None of us can walk away from this battle unharmed.”

Perez also weighed in on Grimes’ statement: “She might have a legal team to fight something like that, but smaller artists do not, and I think it’s very dangerous.”

Despite her concerns for the future of the industry, Aiello remains hopeful that the majority of consumers will continue to seek out real music over AI-generated songs. She believes Spotify must be held accountable for its lack of transparency and treatment of musicians, and that it is not artists’ job to “fight the robots.”

“I think there is something so human in real music that AI is entirely incapable of replicating as close as it may try,” Aiello said. “I think consumers know that. I think most people would rather listen to a real person sing about their real feelings than a robot mimic a bunch of other people singing about their feelings.”

“We’re all at risk of AI in different forms, so we can’t really leave each other (behind).” Maco Dacanay, FCLC ’26

So what can be done to fight against the creative theft perpetrated by AI and to support real, independent music?

“We’re all artists together, not just musicians, but actors, photographers, dancers, performers — all means of creativity. We’re all at risk of AI in different forms, so we can’t really leave each other (behind). We have to stick together in this, (because) AI is only going to get better,” Dacanay said.

For Perez, resistance comes in two ways.

“There’s directly resisting these big tech companies by boycotting or switching off of Spotify or the major streaming platforms,” Perez said. “Live music is kind of the lifeblood of the music scene. I think supporting your local scene and going out to shows is a really good way to support these independent artists. And, you know, AI can’t play live — at least not yet!”

You can support local, independent live music on Friday, Sept. 12 and Friday, Sept. 19 at Kayle Rivington, a Filipino restaurant on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Maco Dacanay will be playing two jazz sets from 7 to 10 p.m. on both nights.