I have never been very religious. Although I’ve received Christian sacraments and attended private Catholic schools all my life, faith has played a minuscule part in it. I do not attend mass or any other religious service of any kind. In high school, I mainly used the fifty-minute period as time for a fifty-minute nap. The wooden pews are deceptively comfortable.

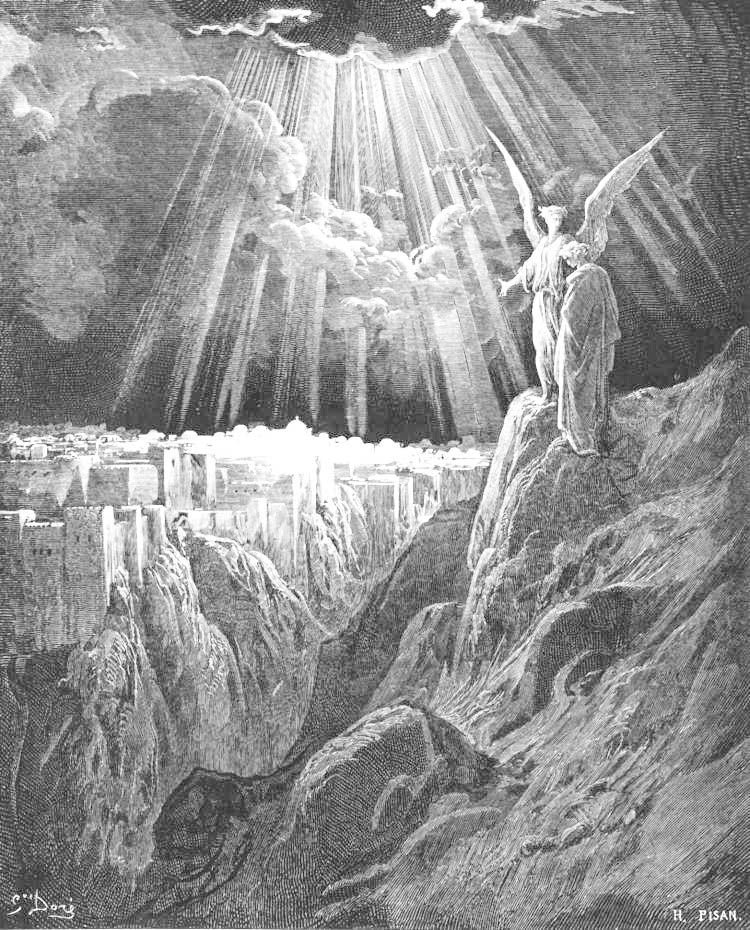

Despite my apostasy, it is not as though I feel my life does not contain any meaning at all. On the contrary, I find that art has consistently given weight to my existence. I may have shed the burden of belief in the Judeo-Christian God, but I do not live my life lightly. I believe art is the vehicle through which we weave meaning into our lives. In other words, the divine comes to us through art.

A reading from a theology class I am currently taking can provide an illustration of this. In Chapter 6 of the Book of Isaiah, the titular prophet receives a message from God to relay to the people of Judah, urging them to give up their wicked ways and to turn back to God. Verses nine and 10 read, “and he (God) said, Go, and tell this people, hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed, but perceive not. Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and convert, and be healed.”

Is turning toward the divine a matter of experiencing without attempting to understand?

Although these verses are open to some degree of interpretation, this passage becomes incredibly thought-provoking if one interprets the closing of eyes and ears as directly leading to healing. This then raises the following question: Is turning toward the divine a matter of experiencing without attempting to understand?

I recently read philosopher Simon Critchley’s newest book, “Mysticism,” which opened my eyes to the beautiful variety of belief systems one can take on. He wrote in his book’s introduction that mysticism “is a form of elevation or healing that does not have to culminate in union with the divine, but which is intensely focused on the presence of God as experienced by the consciousness of the mystic.” The intimacy of this description was already a marked difference from my past religious experiences. In contrast to the hierarchy I had grown used to in ecclesial settings, Critchley’s words on mysticism show an approach of personal dialogue between the participant and the greater world around them. It is the active decision to accept and submit to a longing for the world we are born into to be more than we initially perceive. Emphasized above all else is a focus on experiential — as distinct from strictly contemplative — faith.

It is not as though the type of experience Critchley describes is completely separate from any conceptualization. He writes that “theology can be productive of experience that might — for us — be unlived, but we might be moved by it, and seek to understand it, or strive to imitate it in the mode of an exemplar.” In this sense, writings and accounts of or by mystics are not historical accounts. One reads of mysticism not simply to hear of others’ journeys, but to embark on a spiritual odyssey of their own.

Critchley’s writing struck me so deeply because of the many potential implications of Christian mystical approaches to religion. He writes, “the closest we get to feeling and communicating with an animated universe is in aesthetic experience, and perhaps above all when we listen to music that we love.” Reading this position on aesthetic objects gave me plenty of pause. Many artworks that hold importance for me came to mind. I find myself hoping, needing for my favorite pieces — the works that make me feel as though there is nothing more magnanimous, magnetic or impossible to fully dissect than themselves — to be as divine as they make me feel. I feel as though I have finally begun to understand what many are able to receive from religious ritual.

As I read and reflect on “Mysticism,” I think of the music of American band Swans. In particular, their later records like “The Seer,” “The Glowing Man” and “Leaving Meaning” are sonically ecstatic. Each evoke images of primordial events shaping the world unto eternity. I’ve long enjoyed much of their discography for that feeling — the feeling that I am conversing with something unknowable, something beyond my plane of being. I’ve good reason to believe the traces of this mystical, pantheistic impression was attempted with intention: “The Glowing Man” opens with a pair of songs titled “Cloud of Forgetting” and “Cloud of Unknowing.” While I did not know it upon my first listen, these clouds refer to the medieval Christian mystical text “The Cloud of Unknowing,” a work referenced often by Critchley in his work.

I feel as though I have finally begun to understand what many are able to receive from religious ritual.

I am also drawn to think of my favorite poems by the English Renaissance poet John Donne. The manner in which he writes of love always feels to me as though he were drawing from a much more ancient — and potent — well. His poem “Negative Love” does this rather directly. Donne writes of a meaning or substance found in love that cannot be articulated. He declares to his audience, “if that be simply perfectest / which can by no way be expreset / but Negatives, my love is so.” The love of Donne’s poetry is not only of the people in his life; he writes of the cosmic, the inexpressible grandness with which we experience our banal lives. He writes of that which may only be expressed in negations. He writes of that which can only be described by all that it is not.

Buffalo-based rapper Westside Gunn comes to mind, who, through his music, can become something beyond mortal. His empire is not built of albums; I accept his declaration as he exclaims, “I’m not a … rapper / I’m an artist / I’m a specialist / I’m a culture curator” on the track “Davey Smith Boy.” Gunn’s distinct vocal style, along with his love of fashion and World Wrestling Entertainment, makes it feel as though he belongs to many eras other than the current moment. Nevertheless, he remains on the cutting edge, putting out music at a relentless pace. Consistent references to professional wrestling, cocaine and jewelry craft Gunn into something much larger than life and its mundanity. I dare not equivocate Westside Gunn’s music with a church service, but I am unable to see his work as anything if not extraordinary.

I picture Wolfgang Tillmans’ harrowing photograph of a bridge under construction. “Macau Bridge” deadens its subject, rendering the pillars that would go on to support the completed structure isolated from time, unmoving and unbecoming. Tillmans captures the construction and reshapes its history by placing it into a still image. In my view, these beams become incomprehensible by reason and logic alone. But they become so much more evocative. When I first came across the image, I addressed the pillars in my journal, writing “are you not shaken by the coming corrosion … you stubborn mementos.”

A line of Critchley’s that has stuck with me as I write this article is as follows: “For the mystic, for the devotee, and perhaps for a lot of ordinary people at least some of the time, things take on a transitional, magical quality, alive with powers grander than our own and possessed of a salvific, healing function.” I wholeheartedly affirm. I have turned toward art and been healed time after time. It has made all the difference.

I present this pantheist view of aesthetics while recognizing that verifying the truthfulness of such assertions is not fully possible. I will not attempt to create a universal truth. I choose to say only what I believe. Above all, I wish to show what can be gained after choosing to hear and not understand, to see and not perceive, to let art wash over oneself while offering no resistance.

Georgia Bernhard • May 14, 2025 at 11:49 am

What a terrific essay. I think your whole point is very compelling, and I feel the same way about this sort of thing. Anything in our lives can (and I think often should, when possible) be seen through a mystical lens; we can infuse anything with the magic of a spiritual feeling. And that’s clearly especially true for art. Also… Swans mentioned???

And this was one of my favorite lines: “I wish to show what can be gained after choosing to hear and not understand, to see and not perceive, to let art wash over oneself while offering no resistance.” I really like the idea of committing to giving yourself to art, and letting down your defenses to allow yourself to potentially have a kind of rapturous experience.