Who is really responsible for the objectification of trans women’s bodies? Do producers of pornography contribute to these narratives of ownership? Are they the only ones who do?

And what about the viewers — Is there violence in our voyeurism? Complicity in our consumption?

When we hear these questions, we tend to point the finger in other directions. We shift the blame up, toward the people in power, the proverbial men in the boardroom. Or perhaps we point down, at the lowest of the low, the nameless, faceless men lurking within the anonymity of a comment section.

If you were lucky enough to get a ticket to the Fordham Studio show “Thoughts on Girlcock,” which began its sold-out run on Feb. 26, you were asking these questions and fully immersed within them.

Kylie must stand up for herself as the roles she plays — from naughty schoolgirl to God-fearing girlfriend — chafe against her morals and begin to feel suffocating, like the red scarf she wears to hide her Adam’s apple at Evan’s suggestion.

In a fitting manner, the play, written and produced by Ryann Lynn Murphy, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’25, begins with the audience placed before a laptop keyboard, as if contributing to the porn site comment section scrolling across the screen. This is far from the only time the viewer is implicated in the story, which follows Kylie Johnson (Murphy), also known as Destiny Starr, a trans porn star whose meteoric rise to fame is threatened by a shady studio contract and her sunny boyfriend’s stormy Christian mother.

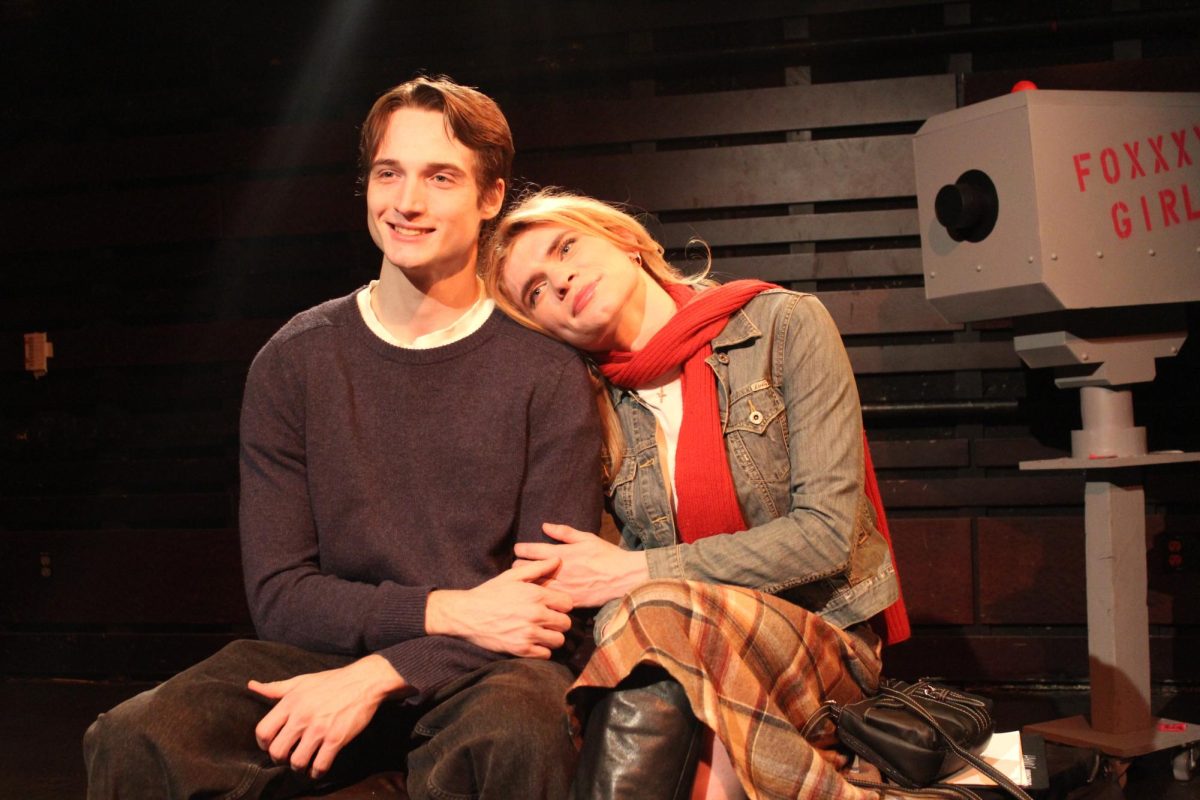

We first meet Destiny in the hammy set up to a staple of the genre, a pizza delivery guy scene (“XXXtra Sausage Edition”) — and when the director calls “cut,” we meet Kylie, the girl behind the star. Besides some reservations about the objectifying jokes her director Carlos (Elian Rivera) insists on including in the script, things are going well for her. Kylie is desired by her endearingly simple boyfriend Evan (Dylan Stern), and admired, if pigeonholed, in her field.

But soon, Carlos presents the prospect of an exclusive contract to Kylie, and Evan introduces her to his “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” mother (portrayed by an instantly funny Fiona Nealis, FCLC ’27). Kylie must stand up for herself as the roles she plays — from naughty schoolgirl to God-fearing girlfriend — chafe against her morals and begin to feel suffocating, like the red scarf she wears to hide her Adam’s apple at Evan’s suggestion.

If you were not lucky enough to snag a seat, you are not alone.

“We sold out in five minutes,” Murphy said.

Due to this demand, the play opened its doors for three invited dress rehearsals prior to opening night.

“Usually dress (rehearsal) is not invited unless you feel really good about it, but luckily we felt really good about it,” director JuJu Jaworski, FCLC ’24, said.

Adding three additional shows to the regular four-show run is neither typical nor easy — Jaworksi said it’s “like a marathon” — but the director attributes the collaborative spirit of the creative team to a tech week that “felt very seamless.”

The synergy of the designers was evident in the immersive experience of the play; the audience’s journey through the probing lens of a porn studio’s camera was directed and distorted by the sound (by Stanley Gagner, FCLC ’26) and lighting (by Soraya Rastegar, FCLC ’28). Set designer Raquel Sklar, FCLC ’25, and props designer Natalie Foo, FCLC ’25, transformed the Veronica Lally Kehoe Studio Theatre into a sleazy Los Angeles porn studio. The set was complete with cameras, lines of cocaine on the house railing, and posters plastering the walls with taglines like “PUMP ME UP,” “DRIVE ME WILD” and the inevitable “HELP ME STEP BRO!”

Even before the lens turns to face the audience, our immersion in Kylie’s world where viewership is currency asks us to weigh the cost incurred by how, and to whom, we pay our attention.

The creative vision, brought to life by a cast of animated actors, finds its foundation in Jaworski and Murphy, who previously collaborated on last semester’s similarly unapologetic Fordham Studio show “Scouts” in the Whitebox Theatre.

“A lot of the time it feels like we’re wearing the same brain,” Murphy said. “Everything is a conversation. Everything is a question … Everything is just throwing spaghetti against the wall and seeing what sticks.”

The gem of their open-minded playwright-director dynamic arrives in the final moment of the show, when the camera is literally turned on the audience. This conclusion was devised in a moment of experimentation during tech week.

“That was like the coolest director moment ever of like, ‘This is a collaborator who hears me, and who I hear, and we just really care about making the most impactful show,’” Jaworski said.

To start the show, the antagonists at the beginning of Kylie’s journey verge on the cartoonish, which mainly serves to contrast the way the lines of oppression tangle and complicate as the story progresses. It is easy, at first, to condemn the threesome of suit-and-tie porn studio executives arguing about the marketability of “transgendereds,” like a sleazier version of the “Barbie” Mattel boardroom. But things get more complicated as the line between porn and reality — and in turn, the line between observing violence and being complicit in it as the audience — begins to blur.

Even before the lens turns to face the audience, our immersion in Kylie’s world where viewership is currency asks us to weigh the cost incurred by how, and to whom, we pay our attention.

“Thoughts on Girlcock” ended its run in the Kehoe Studio Theatre on Feb. 28.