During the 2016 presidential election, Natalie DeMartini’s family came up with a simple rule: bringing up politics was off the table.

DeMartini, Gabelli School of Business at Lincoln Center (GSBLC) ’28, said that political differences within her family had reached an all-time high. Since the rule, according to DeMartini, political tension within her family has lessened.

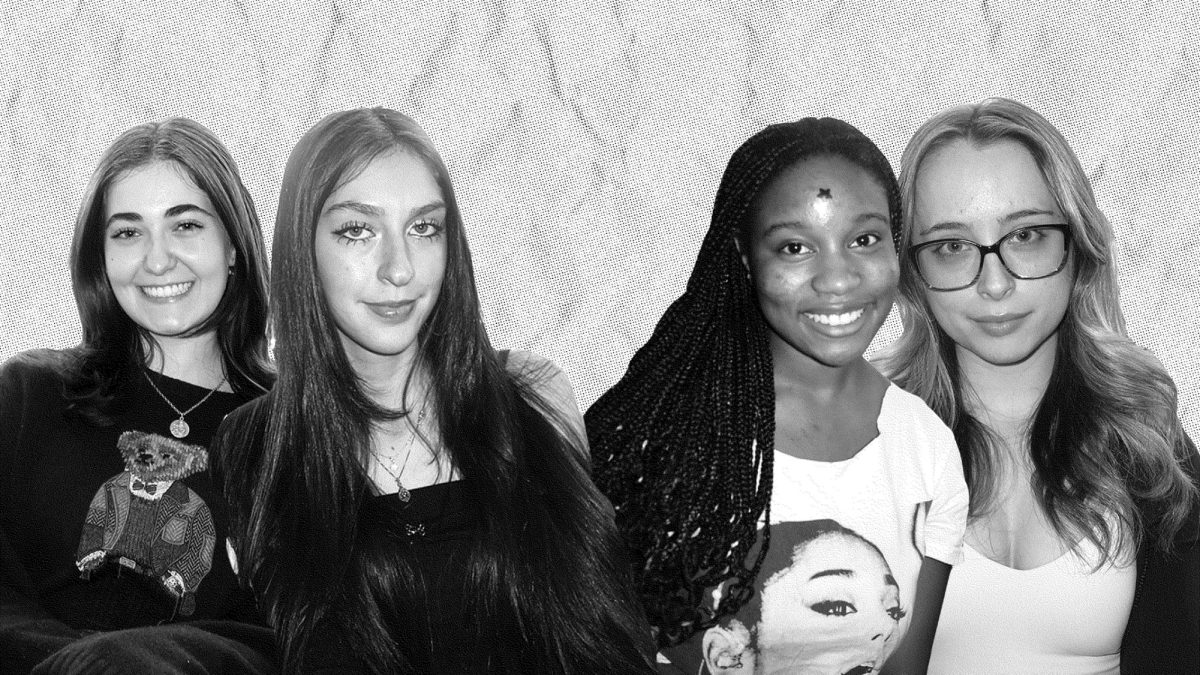

Almost a decade after DeMartini’s familial rule, politics is still impacting relationships. Fordham students meet new people and grapple with how best to navigate politics in friendships. Some say that blocking out any political differences is best, while others argue that politics should take a back seat in relationships. And one approach redefined politics as important and still somewhat unthreatening.

Widening the Chasm

Instead of purely adopting her family’s rule about political discussions, DeMartini took a singular approach to alleviating tension.

“All my friends have the same political view as me,” DeMartini said, “and I would like to keep it like that.”

This way of thinking — of making politics so integral that cohesion is the ideal — is one way to deal with differences in a new place. On the edge of the widening chasm of political differences, sometimes it feels easiest to stick to one side.

Kennedi Hutchins, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’25, said that she “tried to have that understanding” when it came to voting for President Donald Trump in 2016. Hutchins said that Trump’s first campaign was an unknown variable.

“We didn’t know who he was,” Hutchins said.

“All my friends have the same political view as me, and I would like to keep it like that.” Natalie DeMartini, GSBLC ’28

But now, she’s thinking about political affiliation differently. Hutchins said that, “whoever you support does represent your morals and how you move through the world.”

“You’re still choosing that person to represent you,” Hutchins added.

Nine years after Trump’s initial victory, she said she lacked that understanding for those voting for him.

Chelsy Veras, FCLC ’26, shared a slightly different view. She agreed that the way someone votes, especially with this election, “says a lot about their morals.” As a result, she said she distances herself from those who cross her moral boundaries. People spouting racist or homophobic ideas are unwelcome in her sphere.

“I do not develop relationships with people like that,” Veras said.

But as long as their opinions don’t cross her moral line, Veras said that “those are my only boundaries.”

Other students at Fordham said that they are taking a different stance — one that argues that some relationships are too important to get lost in the growing divide.

Ignoring the Chasm

Elizabeth Ward, FCLC ’28, said she has repositioned politics to the back burner when establishing friendships.

She said that political debates are something she does not “typically talk about with people — because it can be very triggering.”

Ward was raised religiously in Miami, but did not like that “pastors often brought politics up in their sermons.”

“Regardless of our differences we should find a way to be able to talk about them.” Dr. José Alemán, Fordham professor of political science.

As a result, Ward has separated her religious beliefs from politics.

“Being raised in that environment has trained me to cope with having a friendship or getting to know someone outside of their political beliefs,” Ward said.

Similarly, Mia Donnelly, GSBLC ’28, has strong convictions for her own voting practices and those of peers. However, she said that even though her parents voted differently than her, “I would never, obviously, stop loving my parents.”

Donnelly said her parents, whom she loves before ever considering politics, are more than their vote. She said that you can pick your friends, but your parents are predetermined. After all, when it interfered with her parental relationships, Donnelly was able to deemphasize politics.

Bridging the Chasm

Dr. José Alemán, a professor of political science at Fordham, articulated an additional approach.

“Regardless of our differences, we should be able to find a way to be able to talk about them,” Alemán said.

Although the tolerance of differences is “case specific,” we still ought to “approach one another with love,” Alemán said.

“Let’s be open to perhaps a change in mind,” the professor added.

But even in those earnest attempts to bridge across the political chasm, things can get lost in the fog.

Those kinds of conversations can be hard. Lillian Kleiderlein, FCLC ’28, found that out first-hand. Initially, she was not too preoccupied with politics.

“Surrounding myself with people different from me is also important — because you learn about all walks of life,” Kleiderlein said. But the results of this past election led to a feeling of separation. They brought Kleiderlein to the realization that “my friends are probably voting against me.”

In order to address this feeling, she decided to have “lots of long phone call conversations — maybe some arguments.”

Kleiderlein found it difficult to connect with her friends during such discussions.

“We try to keep it as mature as possible,” Kleiderlein said.

But even in those earnest attempts to bridge across the political chasm, things can get lost in the fog.

“It can be frustrating and heartbreaking when they don’t see where you’re coming from,” Kleiderlein added.

Chara Blagrove, FCLC ’28, talked about a similar situation — one that acknowledges the importance of both politics and relationships.

Blagrove had a close friend — so close in fact, she said, that if she “got married tomorrow, (she) would’ve been my maid of honor.”

But when she learned that the friend voted differently, she chose to instead embark on a series of political conversations directly confronting her disagreements.

In these conversations, a tennis-like rally sparked off between Blagrove and this friend. Both would articulate their opinions on the political landscape and provide the rationale behind them. In these exchanges, Blagrove was able to identify possible misunderstandings in the opposing argument.

In understanding the perspective of the opposing side, Blagrove was able to more effectively listen to her friend. She described these talks as deconstructive conversations — where, in order to salvage a friendship, both parties looked for resolution. They analyzed their own views, noticed faults and listened to responses. This led to a healthier debate and an even stronger respect for each other.

Blagrove said that her friend’s voice is inside those disagreements in opinion. When dealing with her relationships, she is more concerned with how her peers relate to Trump than with Trump himself.

“I think it similarly shows immaturity to say that if you voted for Donald Trump, I don’t like you,” Blagrove said.

To Blagrove, truly acting with maturity means seeing the political differences, “and then also being able to dissect that with another person.”

For Alemán, the central question for much of these conversations is “if we agree that there’s a problem, based on the facts and the evidence — then how do we go about fixing, or solving it, or possibly ameliorating it?”

And at least for a few Fordham students feeling that burden, deconstructive dialogues with close friends might be worth the effort.