If you wandered into Ildiko Butler Gallery on the evening of Jan. 15 with only a cursory knowledge of the photographs on display, you might have been surprised to hear a distinctively bright voice call out, “What’s your favorite picture?”

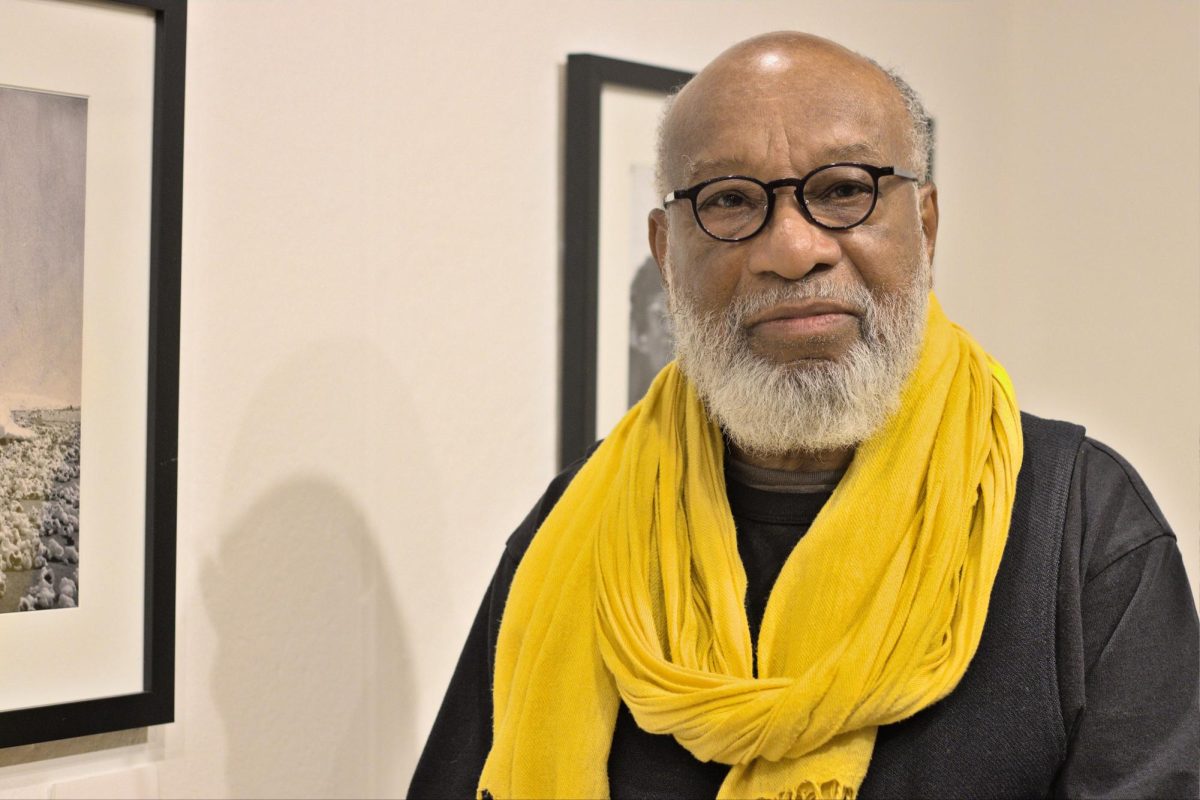

That voice belonged to Chester Higgins — a former staff photographer at the New York Times recently inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame, and the artist behind astonishing images of Black spiritual life featured in a collection called “The Intimacy of Prayer.”

The black-and-white photographs display subjects of various faiths — including Christian, Jewish, Spiritual Baptist and Candomblé — engaged in what Higgins calls “the universal act of supplication.”

In one image titled “Trinity Ethiopian Orthodox Church,” taken in 1990, the camera peers down at a man bent over his upturned hands. The shot centers on the crown of his head, while a slight blur conveys his momentum. In another, “Boy At Window During Service Break” from 1968, a young boy’s resolute face is aglow with light from a window; he seems in silent communion with an outsider just beyond the frame. Higgins’ singular focus and natural compositions suffused the collection with a sense of meditation.

“We think of God as being something far away,” Higgins said. “But in prayer, you don’t yell. You whisper.”

Growing up in the 1950s in New Brockton, Alabama, Higgins had a revelatory experience that forever changed his understanding of the world. In the middle of the night, he awoke to the vision of an African man dressed in traditional robes emerging from a circle of light. He was transfixed, then terrified, when the man called out to him.

The black-and-white photographs display subjects of various faiths — including Christian, Jewish, Spiritual Baptist and Candomblé.

Higgins’ family was bewildered by the event, but his grandfather understood it to be a spiritual apparition. Thus began a period of fervent religious education and church leadership in Higgins’ youth that remains the spiritual well of his identity and artistry nearly 70 years later.

“As a young kid, I had a very intense relationship with the church,” Higgins said. “When I went to college at Tuskegee (University), I took a rural religion class, and I found it amazing that God is accessible to so many people but under different names.”

Higgins came to believe that within each of us is the fundamental basis for a relationship with a higher power and the capacity for transcendental experiences like his own. He opposed the idea that spiritual connection requires an intermediary such as a priest.

“You don’t give the power to anybody that you have inside yourself,” Higgins said. “Every one of us is here because there’s holiness in us. But we somehow allow people to legislate the access to that, and make us feel insecure that we can’t access it ourselves without having it authenticated.”

“The Intimacy of Prayer” was presented by the Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs and the Visual Arts Program at Fordham and first opened in December 2024. It previously appeared at Rose Hill in the Refuge Gallery, which highlights artistic work on humanitarian and social justice issues.

Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock, head of the Visual Arts Program, said in a phone call that Higgins’ photos provided a meaningful opportunity for his photography students to respond to the themes from a personal angle.

“Due to the nature of our institution, students found that topic of interest. That’s something that they had opinions on,” Apicella-Hitchcock said. “People were quite open about their relationships to particular images and why they chose them. That’s so unusual.”

He also noted that the exhibit’s tone did not discourage students who were not religious from engaging in the conversation.

“For those that are not of faith, it could feel a bit intimidating or perhaps dogmatic at its worst when you start to bring up this topic,” Apicella-Higgins said. “But the moments were very delicate and very quiet. It was just showing people with their relationships (to God).”

One photo in the exhibit features Higgins’ great aunt, staged to replicate a scene he often witnessed as a young boy when walking to her house. In it, she kneels by a bed with her hands in front of her and her eyes gazing downward. The camera captures her through a window, enclosing her in a private reverie the viewer does not dare disturb.

Higgins came to believe that within each of us is the fundamental basis for a relationship with a higher power and the capacity for transcendental experiences like his own.

Reflecting on the photo, Higgins referred to it as his “earliest story.”

“I knew that the first thing she did in the morning when she got up was she prayed, and that was also the last thing she did before she went to bed,” Higgins said. “So I knew this image. When I started making pictures, I went to her and I said, ‘you should let me do this.’”

Representing the Black community authentically is the major impetus for Higgins’ work. When he first took an interest in photography as a young man, he recognized the power the medium had to augment the disparaging visual narrative of Black people at the time. Higgins was inspired by his mentor, photographer P.H. Polk, whose portrait series of local Black farmers and country folk during the Great Depression moved him deeply.

Higgins brought nuanced depictions of Black people and their communities to mainstream publications over many decades. He photographed people he lived among, people who embraced him on numerous trips to Africa and famous people like Muhammad Ali and Aretha Franklin. Higgins’ lens afforded neighbors and legends alike the grace, respect and complexity they were due.

Despite how he helped transform our perceptions of each other in the world, Higgins remains driven by the spiritual mysteries beyond our sight.

At the reception for “The Intimacy of Prayer,” he engaged with students and passersby in thoughtful conversation about his work and the life it reflected. Surrounding him were the photos he had taken across the globe, in varying religious and ritual contexts, depicting people who all quietly searched for the same thing.

In discussing how the act of prayer served belief, Higgins spoke decidedly.

“The only way to reach your spiritual center is to go into yourself.”

Higgins is represented by Bruce Silverstein Gallery in New York City. His work is part of the permanent collections at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others. One of his photographs is on display in the Met’s current exhibition “Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt,” which runs through Feb. 17.