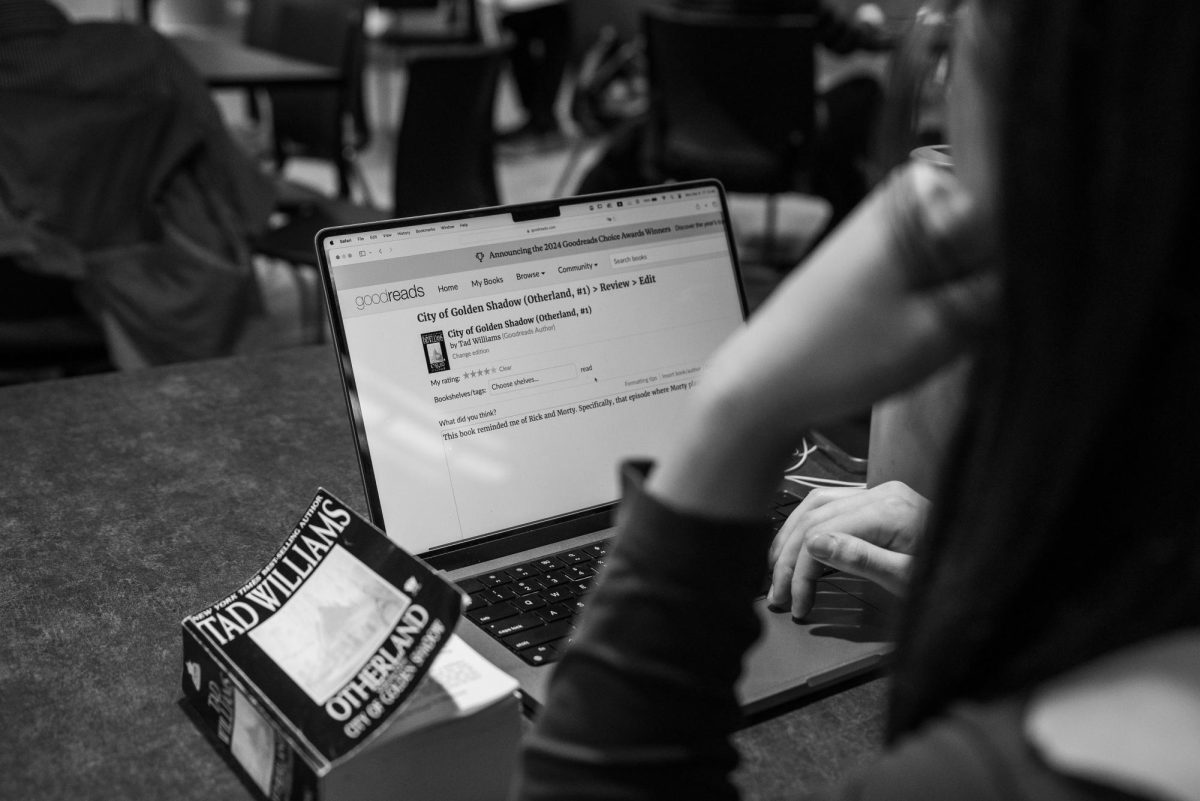

I barely skim the last page of a book before I rush to update it from “Currently Reading” to “Read” on Goodreads. It’s the same feeling I get when I’m watching a movie I’m not enjoying — pushing through just so I can log it on Letterboxd.

I browse the aisles of Barnes & Noble and pick up “A Tree Grows In Brooklyn.” 493 pages. I quickly put it down — it would take too long to read and throw me off track for my 2024 Reading Challenge. I want to rewatch “Napoleon Dynamite” for the 10th time, but it would be unproductive considering all the movies sitting in my watchlist.

I take a step back. I stop in the midst of writing a review to think: When did I start to enjoy logging media more than I enjoy consuming it?

These platforms took off by offering interactive reviews, tracking capabilities and a sense of community.

Letterboxd and Goodreads are online social platforms designed for cataloging movies and books, where users can publicly rate and review what they have watched or read, facilitating the exchange of recommendations and new finds. Letterboxd was founded in 2011, and Goodreads in 2007, but both platforms rose in popularity in 2020 at the height of the pandemic when people suddenly found themselves with more time to consume media. Letterboxd now houses over 13 million users, and Goodreads has amassed an impressive 150 million.

These platforms took off by offering interactive reviews, tracking capabilities and a sense of community. I began using Letterboxd and Goodreads consistently in 2023 because I enjoyed how they pushed me to explore more varied media. I felt motivated to expand my taste across genres and works I would not typically consume.

However, this pressure quickly grew more intense, and I began feeling like I was falling behind. These platforms create a sense of “responsibility” for users to stay up to date on all the latest trending content, and this pressure drives the urge to watch and read more, all to maintain a certain social standing.

Letterboxd and Goodreads are online social platforms designed for cataloging movies and books, where users can publicly rate and review what they have watched or read, facilitating the exchange of recommendations and new finds.

Goodreads and Letterboxd foster environments where you are constantly aware of what everyone else is reading or watching. Like Instagram, you see glimpses of exciting things that others are doing and start to feel the fear of missing out (FOMO) because you are not consuming the movies or books that everyone else is logging and raving about.

This FOMO can make the experience feel more like a race to consume as much content as possible rather than a place to savor and explore what genuinely interests you. It can also lead to the exhausting need to compare yourself to others — who has read more, who has watched the more obscure films, who has the most impressive shelf or profile.

The pressure evolves further, shifting from a general need to consume more media to a need to consume specific kinds of media. Both platforms encourage a kind of “taste performance” where users feel the need to engage with only the “right” books or films, especially those deemed culturally significant or critical darlings.

Such pressure often leads to people avoiding or feeling ashamed of the things they enjoy — like watching cheesy rom-coms or reading genres that are outside of the “high-brow” distinction. Instead of engaging authentically with media, users feel compelled to present themselves as lovers of “serious” or “important” works, even if their tastes are vastly different.

At their core, Goodreads and Letterboxd have transformed what otherwise would be private, personal experiences of books and movies into something that needs to be packaged and presented for an audience. The joy of reading a book or watching a movie is sacrificed for the sake of social validation.

When every piece of media consumed becomes content to be reviewed, rated or compared, the lines blur between personal enjoyment and performative engagement. Instead of feeling free to enjoy media for your own sake, you can start to feel like every moment of consumption needs to be justified or made public.

Instead of engaging authentically with media, users feel compelled to present themselves as lovers of “serious” or “important” works, even if their tastes are vastly different.

Over time, we are conditioned to evaluate media based on what others say is “valuable,” often forgetting to trust our own preferences. I recently watched a popular movie that I did not enjoy at all, but when it came time to rate it on Letterboxd, I hesitated. I felt this underlying guilt, almost as if I were betraying some unspoken standard of sophistication or cultural awareness. I had this nagging fear that others would view me as unintelligent, as though I had not fully grasped the film’s deeper meaning. It’s fascinating how easily we doubt our judgments to fit in with others’ ideas of the “right” way to view media.

It’s ironic, too, that in today’s landscape, humor seems to be the key to validation, often overshadowing thoughtful critique. This is especially noticeable on platforms like Letterboxd, where the top liked or rave reviews tend to be clever one-liners or sarcastic observations. It’s as though being able to make a joke about a film or drop a meme-worthy line has become the most valued form of engagement, adding an extra layer of performativity. Reviews become less about genuine reflection and more about how shareable your take can be.

Given the pressure to consume the “right” amount of media, choose the “right” titles, and review them in the “right” way, how are we actually supposed to use these platforms? First and foremost, users need to consider why they engage with certain content and how much they’re influenced by external pressures. However, if reflection alone is not enough for those who might feel they are caught in a cycle of performative consumption, there are other options to consider.

For Letterboxd, some users have abandoned the traditional star-rating system and embraced a more straightforward approach: heart or no heart. Without the need for a detailed rating, there’s less concern about whether a certain rating might be seen as too high or too low. This encourages a more personal, stress-free interaction with media, where the focus shifts from conforming to social expectations to simply expressing whether you liked something or not.

On Goodreads, I believe it is time to move away from the yearly reading challenges, which track your progress with a precise number showing how many books you are “ahead” or “behind” your goal at any given time; it is exhausting. The constant tracking not only adds unnecessary pressure but also creates a competitive atmosphere. It’s important to remember that even reading one book a year is an accomplishment!

Even though Goodreads and Letterboxd were founded as social platforms, we can still use them in ways that avoid the usual pressures associated with social media. Rather than focusing on likes and followers or comparing our taste to others, we can approach these platforms as tools for personal explorations and genuine engagement with the media we love. By shifting our mindset, we can make these spaces more about individual discovery and reflection rather than feeling the need to perform and conform.