We come to Sally Rooney for magic. We come to her books to laugh, to cry, to care. Because we need that, all of us, that indescribable feeling we get when we flip through the pages of a Rooney novel.

All jokes and Nicole Kidman monologues aside, what really keeps a Rooney reader coming back for more is her characters — honest, raw and authentic. In each of her books, Rooney delivers a portrait of what it means to be human, to exist with other humans, to love, to grieve, to lose, to judge, to struggle, to hope. At the core of her storytelling, she captures the essence of shared experiences, highlighting the beauty and the pain of the human condition.

Following the rapid rise of her career, Rooney’s voice has faced criticism for her thematic focus on the discomfort of the human experience. Some critics suggest that her pursuit of realistic characters creates individuals who are cryptic, contradictory and self-destructive while lazily labeling her stories as “boring.”

Critics who say Rooney’s books are devoid of plot often overlook their realistic depiction of life. And these so-called “unlikeable characters” are simply flawed in a genuine way. Essentially, Rooney’s books are not intended for those who turn to literature for an escape from reality. Rather, they encourage readers to do the exact opposite, engaging in self-reflection about their existence in the world.

By adopting a third-person omniscient perspective — where the narrator knows all thoughts, actions and feelings of all characters — she infuses them with distinct personalities through her writing style.

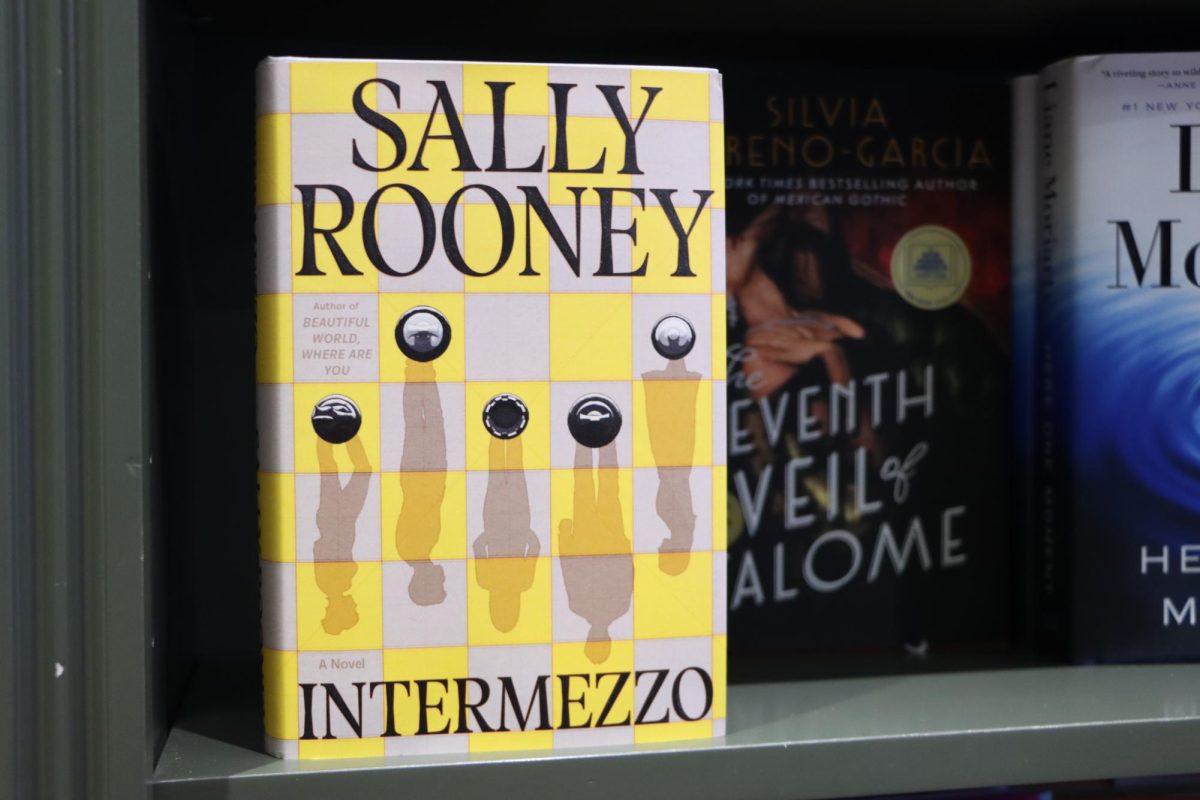

“Intermezzo,” Rooney’s latest novel, is no different in this sense. In fact, it offers a deeper character study of her two protagonists than in any of her books before. Above all, it serves as an exercise in empathy for its painfully frustrating but admirably vulnerable characters.

The story follows two brothers — Peter, 32, a lawyer, and Ivan, 22 — a competitive chess player, as they navigate life after losing their father. Even as they attempt to support each other during this time of grief, a lingering bitterness persists between them, fueled by their contrasting personalities and the age gap that accentuates their differences.

Rooney juxtaposes these two characters by their distinct traits, actions and by their ways of thinking. By adopting a third-person omniscient perspective — where the narrator knows all thoughts, actions and feelings of all characters — she infuses them with distinct personalities through her writing style. Peter’s chapters mirror his fractured psyche, as Rooney omits words and uses fragmented sentences, while the chapters centered on Ivan’s perspective are structured and methodical.

With “Intermezzo,” Rooney skillfully intertwines grief with the complexities of everyday life, illustrating how these emotions coexist rather than exist in isolation

While initially jarring, this choice of perspective — a risky path often avoided by many authors — proves highly effective in “Intermezzo.” It allows readers to delve deep into each character’s mind, particularly in relation to their grief, which is experienced so differently by every individual.

With “Intermezzo,” Rooney skillfully intertwines grief with the complexities of everyday life, illustrating how these emotions coexist rather than exist in isolation. In doing so, the novel engages with several other significant themes, chief among them the deep examination of what it means to be normal.

This central question is illustrated through contrasting extremes in each brother. There is Ivan, often portrayed as abnormal because of his geeky tendencies and lack of social success, but who accepts his uniqueness and rejects the idea of “normalcy.” As Rooney states in the novel, Ivan, “unlike his brother, doesn’t assign an idiotically high, practically moral degree of value to the concept of normality, which phrased in another way means conformity to the dominant culture.” Peter strives to fit into the mold of a so-called normal person, projecting this image to everyone he meets. This pursuit, however, slowly chips away at his sanity.

Rooney effortlessly illustrates her characters and their efforts, or lack thereof, to “fit in” through their interactions with others, especially in their respective romantic relationships. This focus reveals how the desire for conventionality and conformity can limit the acceptance of life’s offerings, particularly one’s capacity for connection.

The brothers are involved in mirroring, unconventional love stories: Ivan with 36-year-old Margaret and Peter with 22-year-old Naomi. At the same time, Peter also grapples with intense feelings for Sylvia, an ex-girlfriend who broke up with him after a serious accident left her with chronic pain.

Although sometimes looked upon as controversial or inappropriate, age-gap relationships, especially as used in “Intermezzo,” open up a conversation about what beliefs and values people hold at different stages of their lives, leading to a deeper understanding of what really constitutes a meaningful life. Ivan and Naomi, attach no significance to “meaningless social conventions.” While Peter and Margaret are consistently haunted by the fear of others’ opinions.

There’s a lot of value in reading both sides of this theme and of every theme present in the story — grief, normalcy, love, regret and masculinity. The age gaps in each relationship, whether siblings or partners, highlight a universality in the human condition, a central focus of all Rooney novels.

In every encounter, conversation and internal reflection that occurs in “Intermezzo,” its readers are ultimately forced to reflect on one of the novel’s stand-out lines: “What constitutes a life worth living?”

Rooney delivers exactly what she has always promised — a deep exploration of interpersonal relationships that challenges societal conventions and invites readers to engage with their own realities.