Jets and Sharks Rumble on the Plaza

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of West Side Story’s Broadway Debut

May 29, 2011

Published: October 25, 2007

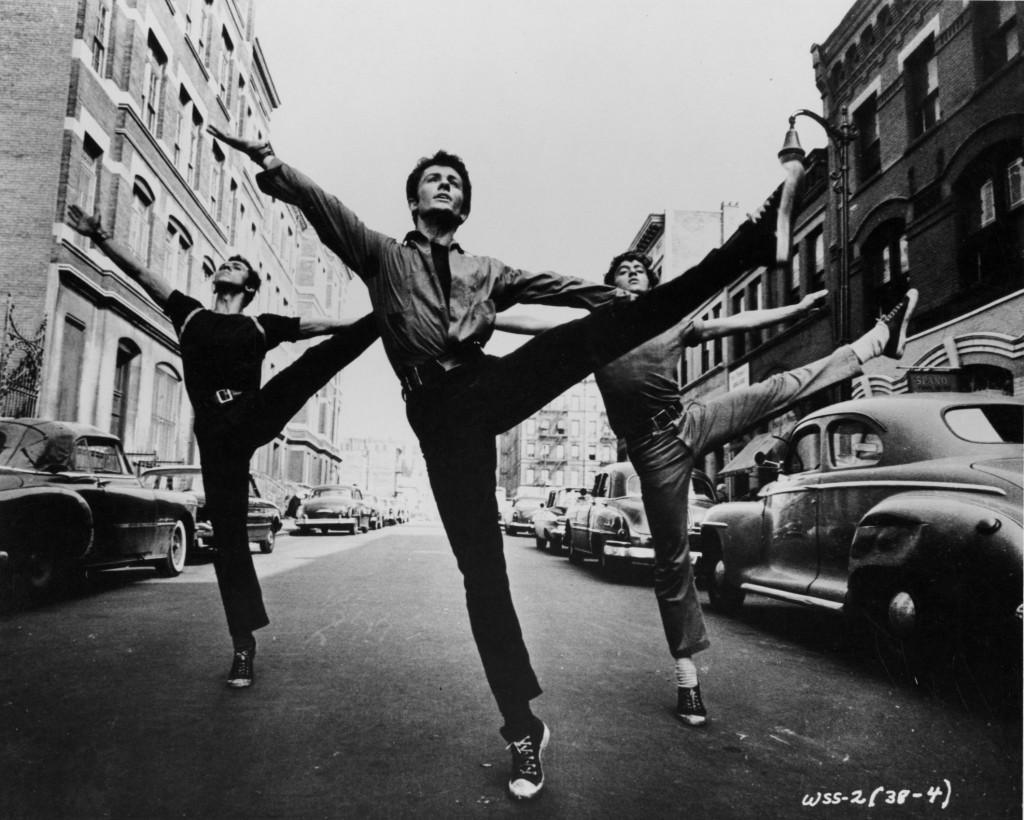

More than 50 years ago, on the Upper West Side, in the neighborhood that would later be home to Fordham College at Lincoln Center, gangs of Puerto Ricans and ethnic Americans rumbled over turf that would later include the Plaza, McMahon Hall and Lowenstein Lobby. Those violent gang wars were immortalized in the groundbreaking musical “West Side Story”, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, and in the 1961 film version, which was partially filmed on what would become the FCLC campus.

Arthur Laurents, Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins (a very young lyricist, named Stephen Sondheim, was later also brought on to join the team) originally wanted to adapt “Romeo and Juliet” into “East Side Story,” a musical about battling Jewish and Catholic gangs. But in the world of the late 1950s, that was a conflict of the past, and the creative team decided instead to rip their story from the headlines of the day; so the white ethnic Jets and Puerto Rican Sharks were born.

When “West Side Story” opened on Broadway on Sept. 26, 1957, it brought gritty, realistic violence to the musical stage for the first time. In The New York Times review, Brooks Atkinson described the musical as, “A profoundly moving show that is as ugly as the city jungles and as pathetic, tender and forgiving.”

Professor of communications and media studies Monique Fortune said, “Finally, on a Broadway stage—we really begin to confront the evil of racial tensions and how hate can literally damage and destroy minds, bodies and souls.”

In this work, Robbins introduced a new, powerful kind of movement to the stage. While choreographing the show, Jerome Robbins discovered a new way of putting movement on stage—he combined stylized versions of the real-life movements of the gang members, Latino rhythms, with the preexisting show dance vocabulary. As Fortune said, “Every possible human emotion…was extended by all the dancers in such a contemporary…and moving way…Jerome Robbins brought the audience such a gift through his choreography—the power of dancers as true storytellers.”

The legacy of “West Side Story” is still seen very strongly in today’s crop of Broadway hits. Fortune felt that “Rent” was strongly influenced by “West Side Story.” “Jonathan Larson [the composer/lyricist] was bold, fearless and unapologetic as he commented on the issues of this day just like Bernstein and Sondheim did 50 years earlier…. The same realities… love, racism, sexism, classism, economic strife…were also examined in ‘Rent’.”

“Every musical that asks an urgent social question owes a debt to ‘West Side Story’,” commented theater chair Matthew Maguire. He remarked that “Spring Awakening,” for instance, continues in this tradition, exploring “how a puritanical vision of sexuality acts as a destructive force in adolescence.”

“West Side Story” is being honored on many fronts during its big anniversary: The Library of Congress is putting together a commemorative exhibit called “West Side Story: Birth of a Classic”; Decca Records is releasing a new studio recording of “West Side Story”; and a collection of recording stars from the past 50 years will be singing the Bernstein/Sondheim classics on a series of discs called “A Place For Us: 50 Years of West Side Story”. Of course, no celebration of a musical is complete without a Broadway revival, so next year Arthur Laurents himself is directing a brand new production, with Tony winner Jerry Mitchell the rumored choreographer.

As FCLC prepares to expand and redefine its place in the community, it might be helpful to look back at the piece of our history immortalized in “West Side Story”. Most importantly, however, at this milestone anniversary, we should remember to look at “West Side Story” for its place in theatrical history—as a landmark work that expanded the horizons of the musical, allowing it to explore far darker territory than ever before.