Courses on cursive writing are a contentious topic in the field of children’s education. Although these classes are not mandated across public school curricula, this style of penmanship — which dates back to the eighth century — should be taught nationwide because of its longstanding history as an artful form of writing and its continued relevance in American culture.

The United States Common Core State Standards, a framework developed for U.S. states to standardize general aspects of nationwide public school curricula, do not require instruction in cursive handwriting to be taught in schools. However, 23 out of the 50 states include cursive writing courses in their state curricula. Clearly, cursive is still valued as important enough to teach, though this sense of value in cursive is not unanimous.

Opponents of cursive writing courses argue that they are time-consuming and useless, while proponents appeal to its extensive history and benefit to writers. Both sides of the cursive writing argument ignore what’s really at stake in placing these courses in our curricula: an education where students engage with culture instead of only being robotically prepared for routine standardized testing.

Cursive should be taught to students for cultural reasons rather than practical reasons. The real question is, why shouldn’t we preserve the formal script that has been present in our country since its inception?

Cursive forces writers to think about writing in a more tangible way than pressing keys to make easily-deleted letters appear on a screen, and allows writers to conceptualize writing in a more artful way than simply writing in print would.

As a cultural form, cursive writing has developed alongside the English language and has been the valued mode for writing in English for centuries. The ability to write in cursive used to be a status symbol, but with its widespread instruction in public schools, it became a democratized skill that reflected engagement with the English language at the aesthetic level. If the emergence of the typewriter didn’t stop people from teaching cursive, why should the emergence of the computer be any different?

Due to the Common Core Standards, the way we as a country think about education is not in its inherent value, but rather in its utility. School curricula focus on fulfilling goalposts provided by the state in order to secure funding and eschew any other topic that might not be required by the state, but is still important. While cursive handwriting will not show up on state standardized tests, it is a regular occurrence in daily life — students will assuredly encounter cursive when studying history or experiencing art. Education should culturally prepare students.

Although I went to elementary school in Westchester County, New York, where the implementation of the Common Core Standards solidified the end of mandatory cursive in 2010, I learned the stylized script as a third grader in 2012 because I attended a private Catholic school that is not obliged to follow the standards. Cursive should not be a privilege of attending private schools that are relatively free from the claws of the Common Core — universalizing the instruction of cursive writing would ensure that it does not revert to becoming a status symbol again, and that it is taught by public and private schools alike.

There are several arguments often employed in favor of mandating cursive writing, but these arguments are dependent on the utility of cursive writing instead of its cultural history as a formal script.

A common argument among educators and education specialists who promote the use of cursive handwriting is that it’s faster to scribe than print handwriting, making it an optimal way to take notes. Not only has this argument been factually disproven, but it has also been taken at face value — efficiency is not a good enough reason to teach cursive.

Students can write just as quickly in print handwriting. If speed in handwriting is so important, why not just teach students shorthand — a specialized set of symbols created for maximally quick transcriptions of diction?

The real question is, why shouldn’t we preserve the formal script that has been present in our country since its inception?

A slightly more compelling utilitarian argument is that learning cursive is beneficial for brain development — children who learn cursive writing have been proven to have strengthened motor skills, improved memory and a greater understanding of spelling, especially in relation to phonetics. However, print handwriting also builds motor skills and memory when compared to typing, making the argument that handwriting is beneficial to brain development not specific enough to cursive writing to warrant its place in curricula nationwide.

A perspective from historians leads to another justification for learning cursive. The United States’ foundational documents are written in cursive: If cursive isn’t taught, how can students read important primary documents such as the Declaration of Independence?

Students shouldn’t have to depend on printed transcriptions of primary documents, especially as that process is vulnerable to falsification — American citizens should be able to read their own country’s Constitution without the help of an interpreter: Understanding cursive is vital for that.

The argument for reading founding documents only supports the utility of being able to read cursive, however, and not the necessity of knowing how to write in that style of penmanship. Seen from the perspective of most states’ current education systems, the connection is simply not good enough to warrant time dedicated to learning cursive, especially when handwriting is on its way out in favor of typing.

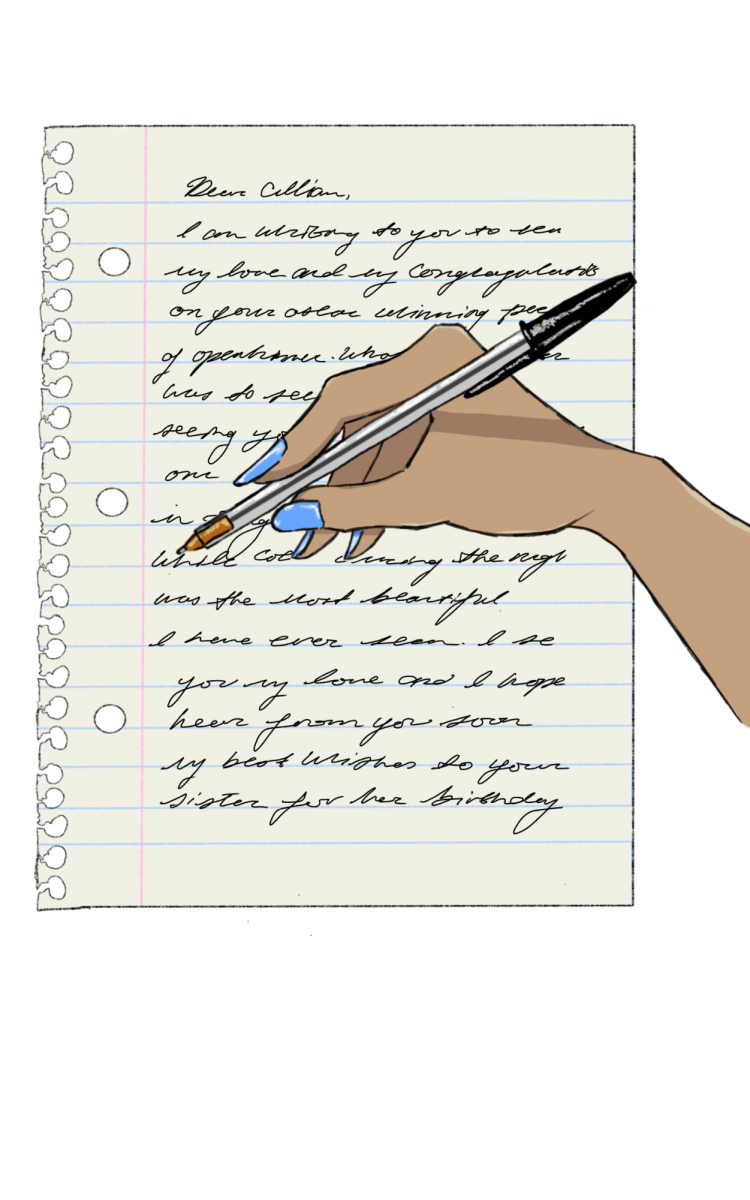

Cursive is culturally relevant because it embodies a personal history. Physical correspondences, captions to old photographs or important documentations from the past are all relics that one can find in their own families and are all likely written in cursive. Cursive plays an important role in connecting individuals and communities with their past — not only should students be able to read cursive, but also write in it as their ancestors did.

Cursive forces writers to think about writing in a more tangible way than pressing keys to make easily-deleted letters appear on a screen, and allows writers to conceptualize writing in a more artful way than simply writing in print would. The controversial form of handwriting should not be debated for its utility, but should instead be considered for its cultural importance. That alone should be reason enough for its implementation in the Common Core.