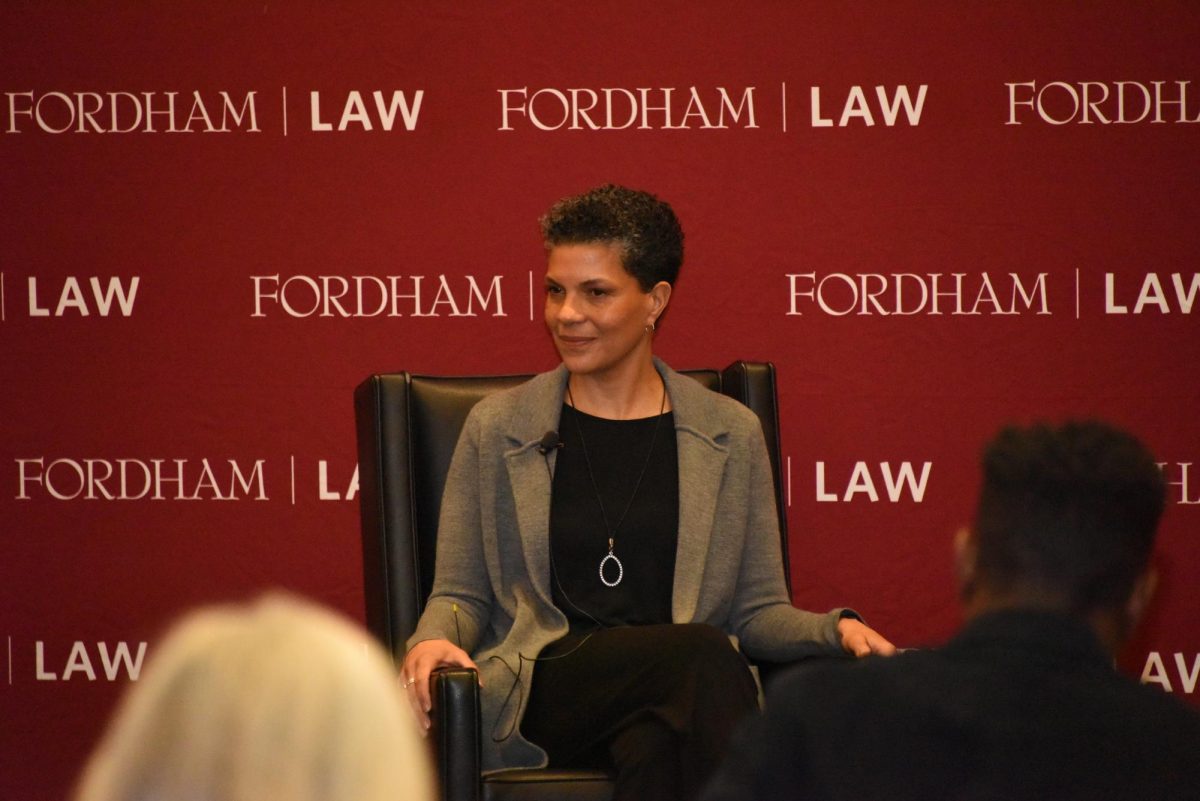

Fordham Law School (LAW) hosted its third annual Eunice Carter Lecture Series on Feb. 22. This year’s event consisted of a moderated conversation with Michelle Alexander, American writer and civil rights attorney who is recognized for her book “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

Alexis Hoag-Fordjour, assistant professor of law at Brooklyn Law School, and Afrika Owes, LAW ’24, co-moderated the conversation. The event was co-sponsored by the Black Law Students Association; the Center on Race, Law and Justice; the Office of the Chief Diversity Officer; and the Office of the Provost.

Alexander has emerged as a prominent figure in the field of civil rights advocacy. As a renowned legal scholar, she has dedicated her career to addressing systemic racial injustices within the criminal legal system which can be seen in the discoveries she made in “The New Jim Crow.” In her book, she argues that the mass incarceration system in the U.S. functions as a contemporary caste system, systematically relegating Black and brown men to a subordinate status.

Matthew Diller, dean of LAW, initiated the event by introducing Alexander and the co-moderators. Hoag-Fordjou led the first part of the conversation. Her first question prompted Alexander to reflect on her time at Stanford and as a civil rights attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

“This idea that as a civil rights lawyer, you can change the world is really intoxicating,” Alexander said. “It’s a very romantic idea, and it kind of casts civil rights lawyers in a heroic role.”

She also discussed how her time representing victims of police brutality made her skeptical about the role of the law in achieving social change.

“I’ve had a series of experiences that prompted my awakening that the system is so much more entrenched,” Alexander said. “We can’t change these systems without accounting for the millions of folks whose voices aren’t heard while civil rights lawyers like me imagine that some isolated victory that revolves around representing the innocent just might have some hope of freeing us all.”

“This idea that as a civil rights lawyer, you can change the world is really intoxicating. It’s a very romantic idea, and it kind of casts civil rights lawyers in a heroic role.”Michelle Alexander, American writer and civil rights attorney

Hoag-Fordjour follows this discussion by asking Alexander about her opinion on “reform and retrenchment” in critical race theory. The phrase refers to the tension between efforts to improve the system through reforms and the simultaneous resistance to those reforms, often resulting in the preservation or exacerbation of existing inequities.

Reform and retrenchment is an element Alexander acknowledges, but she also explains how activists are beginning to identify these cycles and how they take place outside of the U.S.

“Our racial justice movements are inevitably inextricably linked to liberation movements around the world. There are parallels and connections to be made between the liberation struggle posed here in the United States and those in Palestine as well as in other parts of the world, and I see it as a very hopeful moment that we’re getting to learn each other’s history,” she noted.

Ayanna Alexander, Fordham College Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’26 and an attendee of the Eunice Carter lecture, commented on how Alexander argued that Americans need to adopt a less U.S.-centric idea on racism and look at patterns happening elsewhere around the world. She explained how she would have liked to hear Alexander elaborate on this point.

“You have both the literal shackles and the invisible shackles that come with oppression or incarceration or post-incarceration.” Afrika Owes, LAW ’24

“In my experience, there are so many people outside of the United States who have trouble conceptualizing the fact that the United States experiences racism today, that something as potent as what she coined as a racial caste system still exists,” she said.

Owes led the second part of the discussion, which included the Q&A section. The co-moderator began by explaining that she was incarcerated at the age of 17 and discussing how community involvement and investment made her case different from most others.

“You have both the literal shackles and the invisible shackles that come with oppression or incarceration or post-incarceration,” she said.

Building off her experience, Owes asked Alexander how one could bring this community model of lawyering into law school curriculums. The Shriver Center in Chicago defines “community lawyering” as “using legal advocacy to help achieve solutions to community-identified issues in ways that develop local leadership and institutions that can continue to exert power to effect systemic change.”

“Law schools, particularly when it comes to our criminal punishment system, need to stop accepting the system as sort of a given and put the system itself on trial in the classroom,” Alexander said.

“Everything is impermanent. Nothing lasts forever. The American empire will not last forever. So what seeds are we planting?”Michelle Alexander, American writer and civil rights attorney

The final question of the event asked Alexander what keeps her hopeful for future change. Alexander shared that while she had a long period in her career where she felt hopeless, the perseverance and courage of formerly incarcerated individuals kept her going.

“Everything is impermanent. Nothing lasts forever. The American empire will not last forever. So what seeds are we planting?” she said.

Sonya Speizer, FCLC ’24, said that the positive note that the event ended on — specifically Alexander speaking about how an individual can have an impact — was particularly inspiring.

“I think we often think of these big structural issues as too large to solve or kind of permanent, so I think that her emphasis on the individual’s ability to make change stood out to me,” she said.

Liam Hofmeister, LAW ’26, expressed a similar sentiment to Speizer and shared that Alexander’s emphasis on being hopeful for the future despite potential setbacks stuck with him because he has felt similarly discouraged in his work as Alexander did.

“I did direct client services, and it can just be extremely discouraging because you’re, as she mentioned, going up against a system, especially when you’re working with low-income clients,” he said. “Maybe you can get a client a win, but then it’s the next day, you have 10 other people who maybe you can’t help because there’s just a lack of resources.”

Alexander concluded the event by imparting some words of wisdom to future activists.

“The short little time that I’m living and breathing here matters, and what we do collectively matters even more, and that gives me hope,” Alexander said.