Scene I

Marjorie Eliot stood in her Harlem kitchen as she prepared a tray of styrofoam cups. It was a Sunday afternoon in early December of 2023, and that only meant one thing: Jazz.

Outside her door, on the third floor of 555 Edgecombe Avenue, a line of concert attendees had begun forming. Eliot’s intimate Sugar Hill apartment possesses both a literal and figurative warmth that makes out-of-towners feel at home. The Parlor was quiet. It wouldn’t last long.

Soon, a friend named Emory arrived and began pouring chilled cider and snapping on plastic lids as Eliot readied the rest of the apartment for the show, adamant that she didn’t need any help. A tray of fig bars was waiting on a stool behind Emory.

“I used to live a few blocks away,” he said. “I just came in and volunteered to help.”

Someone played a few notes on the piano that sat in the living room. The bassist arrived and began to warm up. Eventually, the whole place was alive with movement and sound. Emory was finishing the cups of cider as Rudel Drears, Eliot’s son, walked in. He began setting up a tripod for the concert’s livestream.

“The music never stopped.”Marjorie Eliot

As Emory put it, Drears is “a brilliant pianist in his own right.” Drears fiddled with the tripod, trying to get the best angle.

“Some people have been watching this, on livestream, that have never come here. Isn’t that something?” he mused. The livestream element of the afternoon was a fairly recent addition, coming as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Drears explained how the pandemic hadn’t just meant a new livestream, but had meant an absent crowd and distanced performers. At this point Eliot walked back into the kitchen and offered her own wisdom.

“We were here,” Eliot said.

“We were here,” Drears agreed.

“The music never stopped,” Eliot concluded.

Scene II

Eliot grew up in the 1930s and 40s, “in a house where everybody played. This is multigenerational,” she said. The same music teacher that educated her mother and aunt also taught her.

The piano tuner lived within eyesight, “and the sound — I loved the sound.” She would even follow him around and watch as he took apart the instrument. “I saw him take all the keys and do all those things,” she said.

Early in her music career, as a “prize” for completing a week of piano lessons, Eliot would have the opportunity to pick out sheet music from the music store. “I loved that, because that is so grown up,” she said.

When Eliot was 12, her first-grade teacher came and asked if she could play at church for the junior choir. It was her first job. The piano tuner taught her how to play the baseline on the organ with her foot: “Oh, did I feel grown up!” she exclaimed.

“The idea of an audience sitting, and you’re right there, is not new to me,” Eliot added. “Doing a concert in the house — I grew up with that. They wanted to show you off when company came and other relatives. You had to do that.”

“I started this here because of the passing of my son.”Marjorie Eliot<

The public Sunday afternoon concerts, though, were instituted to help grieve a family tragedy.

“I started this here because of the passing of my son,” she said.

Phil died on a Sunday.

“Because of grief, she actually found a way to express her grief by honoring Phil by doing these concerts,” Emory said.

“What this does for me emotionally, I can’t even express in words,” Eliot said. “They care about me. They care about each other. And we are more alike than not.”

Eliot has come to view the guests as not just consumers of her production, but family: “That’s how they see it, and that’s how I see it,” she said.

Scene III

The gaggle of audience members streamed through the door, past the kitchen and into the parlor. Rows of folded seats awaited them, each donned with a red cushion.

In these seats, hundreds of people on hundreds of Sundays have sat and listened to Marjorie’s Jazz troupe, Parlor Entertainment, play their hearts out. In these seats, countless conversations have been held about the joy of music and the pain of life. Some have come for healing, others have come for worship.

Eliot entered stage left. She spoke above the applause to introduce her bandmates.

“Sedric Choukroun!” she announced to the Parlor with an outstretched hand. Choukroun took a deep bow with a clarinet in hand.

Choukroun moved to New York City in 1999 and rediscovered the wonder he had first felt during a summer in the city a decade prior. “I found my 17-year-old self back here,” he recalled.

“I have someone that I can introduce you to,” a photojournalist friend told Choukroun weeks into his new life in New York. Eliot — always on the lookout for new talent — noticed Choukroun’s saxophone case on the floor. After asking if he played, she said, “The next solo is for you.”

“So I just took my horn out, wet my reed, and then she almost pushed me in,” Choukroun remembered.

“He never left,” Drears said. “It’s kind of funny. It really is that simple. He came with a friend. He sat in. And never left.”

Chourkroun met his wife at a “Singer’s Workshop” that Eliot hosted on a Saturday afternoon more than a decade ago. Now, audience members watch him play in front of a wall plastered with pictures of his son; the “Parlor Baby,” as they call him. “There’s even pictures of him when he was two weeks old and then all through the years,” Chourkroun said.

“Nicholas Mauro!” Eliot announced next. Mauro nodded with a smile.

Fresh out of school with a masters in education, Mauro had contacted The Jazz Foundation of America to see if they would send musicians to expose his new students to the tradition.

Mauro, raised in New Haven, Connecticut, comes from a family of artists. Before the age of 10 he had picked out the trumpet while on a trip to a music store with his father; he’s “been doing that since,” and now even teaches music himself.

The Jazz Foundation, a group dedicated to supporting struggling musicians and sponsoring concerts in low income schools, granted Mauro and his class at The Children’s Storefront four concerts. Parlor Entertainment showed up first — it wasn’t long before Eliot learned that Mauro played the trumpet.

After the concert, he was the one being asked, now by Eliot, to come and play in her apartment.

Admittedly, Mauro was confused as to why the concert was in Eliot’s apartment, but after hearing her story, he was in. “Then she wanted me to come after that once a month. Then it was every other week. Then it was every week,” he said. “The rest is kind of history. We just clicked.”

That was September 2012, and since then Mauro has been a consistent brass player with Parlor Entertainment.

“He’s a fabulous teacher,” Eliot said. “Very patient and loving with the children, all age groups.” When Mauro would bring students to her apartment concerts for field trips, they would ask her if they were allowed to call him Nick (since they weren’t at school). “Yeah!” she would say. It made her giggle.

“I haven’t gotten tired of it,” he explained. “I’m not even thinking about notes when I’m there — or chords or anything. I’m thinking about how we’re going to blend together and make something that’s going to sound good to the audience.”

Mauro still teaches during the week — now at a school in Kips Bay — playing in the Parlor on the weekends. “We’re all a big family but there’s definitely nothing else like it that I’ve experienced,” he said.

Ms. Eliot turned to the bassist, then to the crowd. “Yuma Takagi!” she declared. He took a big bow. He was the band’s current bassist. When the previous one passed away, Mauro brought him aboard; he said “I know a guy.”

“We fell in love with Yuma the minute he started playing,” Eliot said.

Takagi grew up in the countryside surrounded by mountains and lakes of Shiga, Japan. He was introduced to music by his father’s records and instruments, and was inspired to play by his brothers’ influence.

That Sunday was incidentally Takagi’s birthday, which meant a hearty birthday song near the end of the night.

Scene IV

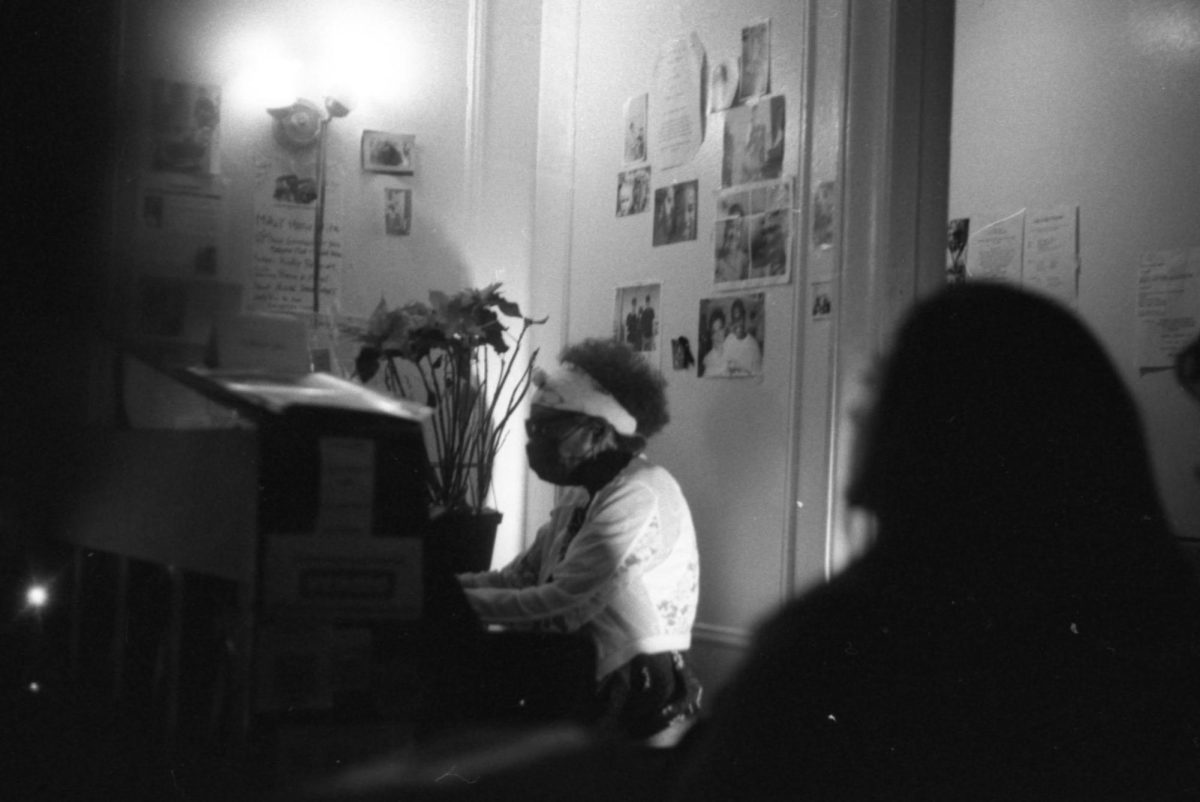

Eliot and Drears took turns playing a few songs each on the piano. The rest of the band cycled in and out from song to song. There were mellow solos, rambunctious trios and copious applause.

Drears nodded along to the music from behind the piano. Jazz had been so essential to his childhood that he wasn’t able to say how long he’d been playing.

After his mother, his next teacher was Mary Kirk – wife of Andy Kirk, “one of the great band leaders of Harlem.”

He remembered when these Sunday afternoon concerts actually began to be a thing. “We had a few prototype concerts in ’94. But every single Sunday? June 1995. I’ll let you do the math,” he said.

For a few years, he was the primary pianist of the group as Eliot focused on producing the show.

“One moment it’s four years,” he said. “Then it’s fourteen years.”

Scene V

At the end of the show — before the final song — Eliot got up from the piano bench, took center stage and delivered a monologue.

“This is where I applaud you,” she said. “You are the critical piece of this story.”

Eliot talked to a packed house populated with people whom she knew by name and also some who were strangers. Even so, her words didn’t reflect this potential disconnect.

“You’ve taken a story — incredibly sad — and you brought joy to it and given great purpose to the story. You’re my family, you took me in, you took us on and made me better. I look at the world in another way,” she said.

Eliot’s message then turned from herself to “our children who are being slaughtered and abused all over the world.” It feels as though there is no way for us to do anything about it, she said. “But we can. We have each other. And we must promise that we will care for them on this side,” — at this moment she paused as her hand reached up toward the ceiling — “and on the other side. Their stories must be told. It’s up to us to do that. You can do it, because I know what you’ve done for me.”

Slowly, the audience trickled out of the room as the band continued to pluck and chat. The livestream replayed on a tablet laying on the piano. Messages from friends popped up on the screen.

Drears strolled around the room, pointing out pictures of former band members and Parlor friends, honoring them by name.

“Every single Sunday? June 1995. I’ll let you do the math.”Rudel Drears

Bob Cunningham: “He helped build this place; passed away 10 years ago at the age of 88.”

Gaku Takanashi: “Sedric brought us Gaku.”

He pointed to one wallet-sized school picture of a child. “That’s Sedric’s son,” he said. “He’s taller now, Sedric, right? Taller than this picture, right?”

“He’s fourteen now.” Choukroun responded with a smile.

“It’s been that long?” Drears wondered aloud.

Eliot sat in the third row and gazed upon the Parlor. “It started and it grew, because they knew I would be here. I wasn’t going to close because we don’t have enough people. That’s how it started,” she said. “The door has never been closed. I love the people that come here. They give purpose to my life.”