Essayist, novelist, journalist and playwright James Baldwin combined his poetic prowess and unique experience as a Black gay man in 20th-century America to produce some of the most influential works of the Civil Rights Movement.

Baldwin, who lived from 1924 to 1987, wrote many daring essays, short stories and poignant fiction — a collection of work that has labeled him as one of the most powerful voices of his time. He was a man of passion who embodied optimism even in the face of the harshest form of abasement.

The American writer and civil rights activist’s work continuously brought to light the origin of major issues concerning racism in the US by carefully examining surface-level perspectives, myths and misunderstandings to reveal hard-to-swallow truths about ourselves, our lives and our world.

Although Baldwin’s works were published over 40 years ago, many of their central themes still resonate with the racial climate in America today. His candid explorations of race, sexuality and gender challenged, and are still challenging, this nation to uphold the values it promised of equality and justice.

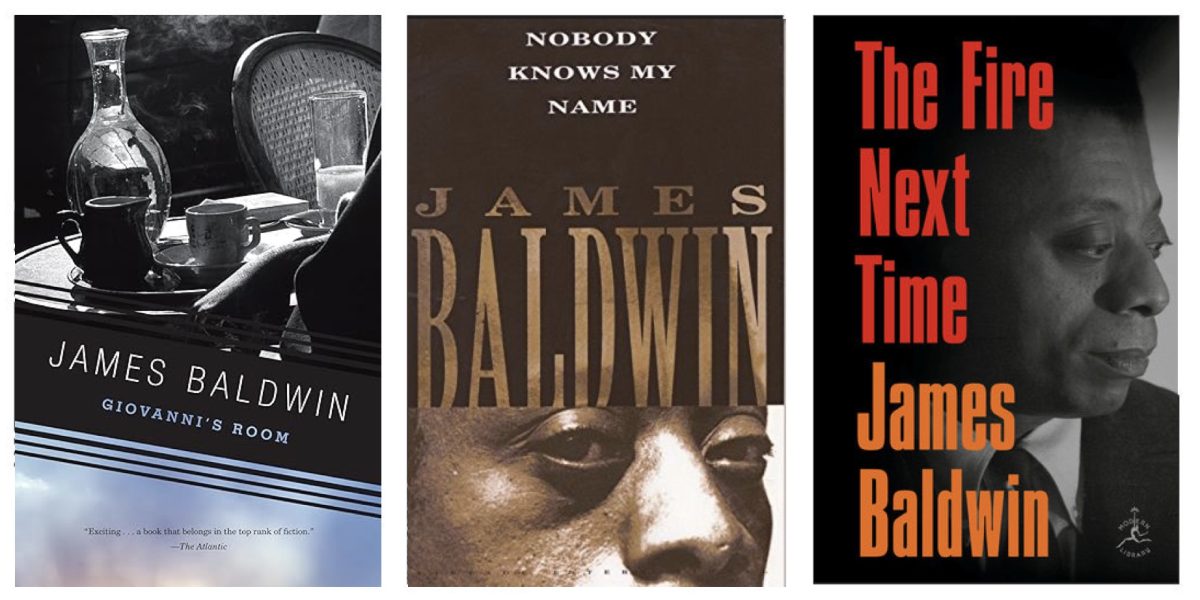

Any reader looking to begin a journey through Baldwin’s bibliography will have to navigate across genres, but his lyrical composition and intersecting themes are distinctive in any form. It is impossible to suggest an “easy-read” due to the nature of his work, but devoting some time to any of Baldwin’s writing helps one to understand his ongoing relevance to our troubled nation. Below are three suggestions that offer a point of entry to his body of work, shedding light on and intersecting race, homosexuality and religion throughout his works.

“Nobody Knows My Name” (1961)

Told with Baldwin’s characteristically unwavering honesty, this collection of insightful and profoundly emotional essays delves into topics ranging from race relations in the United States to a writer’s role in society. “Nobody Knows My Name” follows the years Baldwin faced the question of his identity, traveling from New York to Paris to the American South, and then back to his home in the Northeast.

The author invites his readers into an intimate world of discovery and pointedly states the discomfort his writing might bring to its audience. If nothing else, this is what Baldwin seeks to do as a writer: to force his reader to look grim facts in the face because if we as a society choose to look away, we can never hope to change. This book serves as an ideal entry into Baldwin’s bibliography as it journeys his self-discovery, helping readers to understand everything that shaped him into who he was — a talented writer, a man of fine intelligence and a true ally in the pursuit of making life human.

To take a cue from his title, this is the book from which we can learn his name.

If nothing else, this is what Baldwin seeks to do as a writer: to force his reader to look grim facts in the face

“Giovanni’s Room” (1956)

Baldwin’s second novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” is set in 1950s Paris — vibrant, liberating and hopeful, or so the main character, David, wishes it to be as he flies across the Atlantic Ocean with dreams of starting a new life. David finds himself unable to quell his instinctive desires despite his determination to live the conventional life he envisions for himself. After meeting and proposing to a young woman, he falls for an Italian man, Giovanni, and begins a lengthy affair. A short but powerful novel, “Giovanni’s Room” examines gender and sexual identity, the mystery of love and passion and the qualms of social isolation.

“Giovanni’s Room” is an excellent place to start in Baldwin’s body of work for anyone who prefers fiction to nonfiction. The story itself is a heart-wrenching exploration of doomed love, but the meaning behind this publication goes far beyond its brilliant narrative. With this book, Baldwin became one of the first Black authors to include queer themes in fiction, marking another characteristically bold act by the author.

This short novel transcended the boundaries of the cultural landscape of its time, and Baldwin transcended the boundaries of the identity the world gave him. In interviews, Baldwin noted that race had no place in this novel; he felt that he couldn’t tackle the dual agonies of racism and homophobia at one time. Accordingly, he did not confide in the standard that he must write Black characters. Although fiction, this novel spoke of Baldwin’s character and motives in ways his personal essays never had.

Baldwin became one of the first Black authors to include queer themes in fiction.

“The Fire Next Time” (1963)

Composed of two letters, “The Fire Next Time” is an intimate and powerful examination of the intersectionality of race and religion in the United States and confronts themes of identity, power and the complexities of human relationships.

The first, “My Dungeon Shook,” is framed as a letter to his niece, which details the social struggles faced in the United States by Black Americans in the most vulnerable and honest prose.

Following it, “Down at the Cross” addresses the damage of Christianity on the Black community and recounts Baldwin’s religious journey from teen pastor to atheist. Among many other grievances, he leaves the church due to its inability to love a Black gay man like himself. The title alludes to the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, and as retold in a folk song, God’s next punishment for man will come in the form of fire as it once did as a flood.

Baldwin took the risk of publishing these essays in 1960s America, a world hunting for targets of hatred during a time of heightened political unrest. An era marked by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and antiwar protests, countercultural movements, political assassinations and the emerging “generation gap.” He wrote with fervent passion and urgency for his life, the life of his nephew and the lives of so many generations to come. Tragically, however, the world looked away.

This book might be one of the author’s most difficult reads in style and content, but it is on this list because of its undeniable timeliness. To read “The Fire Next Time” in 2024 is to realize that the “progress” our country prides itself on is not enough. The fact that Baldwin’s words still resonate with the racial climate in our country today should be testament that we must do more. These essays are a plea for change, a plea for country-wide self-reflection and a plea that we should not look away from now on.

Tony Collins Jr • Feb 24, 2024 at 6:10 pm

In ‘The Fire Next Time’ Baldwin is writing to his nephew James and not to his niece.

Ed Higgins • Feb 23, 2024 at 10:38 pm

Baldwin attended DeWitt Clinton high school where he contributed to the school literary magazine along with a young aspiring photographer named Richard Avedon. How’s that for a masthead?