Fordham Should Do More To Support Black Students

Yarl’s shooting is yet another moment where Black people are forced to face the ignorance of their white counterparts

May 8, 2023

Ralph Yarl, a 16-year-old Black high school student, was shot by Andrew Lester, an 86-year-old white homeowner, in the Northland neighborhood of Kansas City, Missouri, while attempting to pick up his younger twin brothers on April 13. The unarmed teenager intended to meet his siblings at a home on 115th Terrace, but instead, he accidentally went to 115th Street. After the homeowner saw Yarl approach his home and ring the doorbell, he shot the 16-year-old once in the head, then again in the arm when Yarl was on the ground, according to Yarl’s aunt who discussed the details in an Instagram video.

Yarl spent three days in the hospital before leaving to recover in the comfort of his own home under the care of family members who are also trained medical professionals.

Lester was charged with first-degree assault and armed criminal action on April 17. He turned himself in to authorities on April 18 and pleaded not guilty to the charges. Civil rights attorney and lawyer for the Yarl family, Lee Merritt, said that the shooter was released in less than two hours after providing a statement to the police and posting his bail of $200,000.

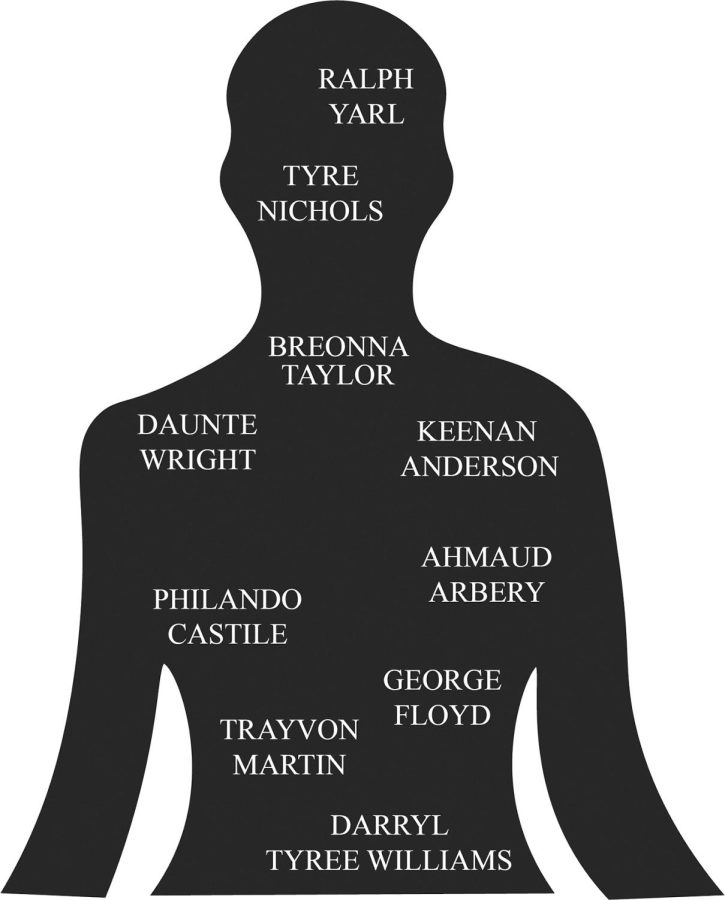

When I learned of the shooting, all I could think was “Here we go again.” Yarl’s story parallels that of countless Black men who have faced violence by their white counterparts, such as Ahmaud Arbery and Daunte Wright — both of whom were fatally shot and received justice only after the public called for it — just to name a few.

White perpetrators of crimes against Black men are often allowed to live peacefully until public attention takes over and calls for accountability dominate the cultural discourse. If Lester were Black, he would not have been able to peacefully turn himself into the police, let alone be released in less than two hours after providing a statement. Instead, he likely would have faced violence from authorities and been treated as a criminal. Justice isn’t always achieved, and the Black community is forced to continue to exist under a system that doesn’t work to protect it.

No matter what, non-Black people will never see the world in the same way that we do.

As a young Black woman, it is suffocating to repeatedly see people who look like me attacked and dehumanized while little is done about it. Since America’s founding, Black people have been criminalized and subjected to brutality at the hands of their white counterparts due to hatred and contempt. It feels as though every day I hear a new story about someone who could’ve been my father, sibling or cousin facing violence simply because of the color of their skin. It is terrifying to reflect on a canvassing job I turned down last summer, for which I would have had to go door-to-door and to know that I could have suffered a fate similar to Yarl.

Recently, while reading updates about the news in between class discussions, one of my white classmates glanced over my screen and inquired about the details of the shooting. As I started to recount the reports, he reacted as if I was sharing a story about something embarrassing that had happened to me.

“Oof … unlucky,” he uttered.

Unlucky: the word used to describe a traumatized, unarmed Black child who had been shot twice for ringing the wrong doorbell.

Was Breonna Taylor unlucky when she was shot while sleeping in her home by police officers executing a “no-knock” search warrant in Louisville, Kentucky? Was Trayvon Martin unlucky when shot by George Zimmerman as he was walking to his father’s house from a nearby gas station in Sanford, Florida? Was Philando Castile unlucky when he was shot by Jeronimo Yanez in front of his girlfriend and 4-year-old daughter in St. Paul, Minnesota?

When I learned of the shooting, all I could think was “Here we go again.”

Throughout the majority of my academic career, I’ve attended predominantly white institutions and have become accustomed to being the only Black person in most of my classes. My classmate’s trivializing comment transported me from my American studies class to my former high school in Washington and has acted as a reminder that, no matter what, non-Black people will never see the world in the same way that we do.

My mind swirled with the microaggressions and blatant ignorance I have had to frequently experience throughout my life. My high school can be described as “liberal to a fault.” The white students loved to boast about their activist mindsets and knowledge of social justice issues, yet they failed to acknowledge their positions of privilege. They neglected to learn how to be true allies to underrepresented communities and, in doing so, directly harmed the few Black students they encountered by alienating them.

The district enjoyed showcasing the influx of new students, especially those who weren’t white, in an attempt to come across as a welcoming and diverse institution. However, it failed to actually offer resources and approach nonwhite students with care. Rather than creating a safe space for students of color, it created a place of security for white students to exist in their privilege and remain oblivious to the reality of the struggles that Black Americans face.

The class of 2026 is Fordham’s most diverse, yet there is still a substantial amount of progress to be made.

Here I am, still one of the few Black students in my classes, in a space where there are few Black professors and limited faculty who would holistically understand my frustration, should I express it to them. As a sophomore, I still feel socially isolated in a space where I expected to thrive due to Fordham’s location at the heart of New York — one of the most diverse cities in the world.

While the university has advanced its diversity, equity and inclusion efforts since announcing an action plan to address racism in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Fordham is not doing everything it can to foster inclusivity across its campuses. The university highlighted its efforts to improve diversity, but few examples can be seen in action. The class of 2026 is Fordham’s most diverse, yet there is still a substantial amount of progress to be made.

The Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) exists at both the Lincoln Center and Rose Hill campuses to provide resources to students of color and promote inclusivity. Aside from first-year orientation, however, I’ve only encountered OMA a limited number of times when members of their office presented at club meetings I happened to attend. Even then, it was the same recycled presentation about implicit bias that I’ve heard too many times to count. If my clubs hadn’t invited OMA to speak, truthfully, I wouldn’t remember that the resource existed.

In terms of education at Fordham, coursework promoting anti-racist ideology has not been easily accessible for Lincoln Center (LC) students. The majority of classes related to race and social justice are offered at Rose Hill, requiring LC students to accommodate their schedule around a cross-borough commute to the other campus. If you asked me to tell you about classes I could take at LC that would help me learn more about the Black experience, I wouldn’t be able to. It would be even harder to think of courses with multiple sections at LC that are taught by Black professors.

Fordham needs to do better if it wants to grow the enrollment of Black students who choose to attend the institution. Using images of Black students on the website at every opportunity to promote the university’s diversity is not the way to acknowledge our existence. The administration must be willing to listen to students who know best what can be done to make them feel comfortable on campus.

For me, a start would be addressing violence against Black people and other nonwhite communities immediately as it happens and offering support to affected students. The last university-wide communication regarding a racially motivated incident was shared on May 15, 2022, after the Buffalo supermarket shooting. While an email from former Senior Vice President for Student Affairs Jeffrey Gray addressed the murder of Tyre Nichols, the school has neglected multiple attacks against Black people this year. Keenan Anderson and Darryl Tyree Williams were also Black victims of police brutality this year, yet the school has not publicly recognized their deaths.

Fordham selectively chooses which initiatives to promote and garner support for, failing to address ongoing issues that directly affect the lives of its students. The school fails to fully use its platform to advocate for its Black students by speaking out against racially motivated attacks. The university needs to wake up and understand that its silence is an act of compliance with the system that fails to protect Black people, including its own students.

While nominally increasing diversity among the student population is important, it is equally important to put underrepresented students at the forefront and support their well-being. Fordham must do better to foster an environment where Black students feel seen and aren’t alienated by other students’ ignorance.

In order to best serve its students and create a comfortable space for them, Fordham needs to actively, vocally condemn violence against Black people as it happens and commit to encouraging its community to embody anti-racism.