Reflections on Alex Katz, Growing Up, and Learning to Look (Alone)

The figurative artist’s latest retrospective highlights 80 years of singular and unwaveringly forthright artwork

Katz’s work reminds us that we are all strangers in the eyes of others.

February 14, 2023

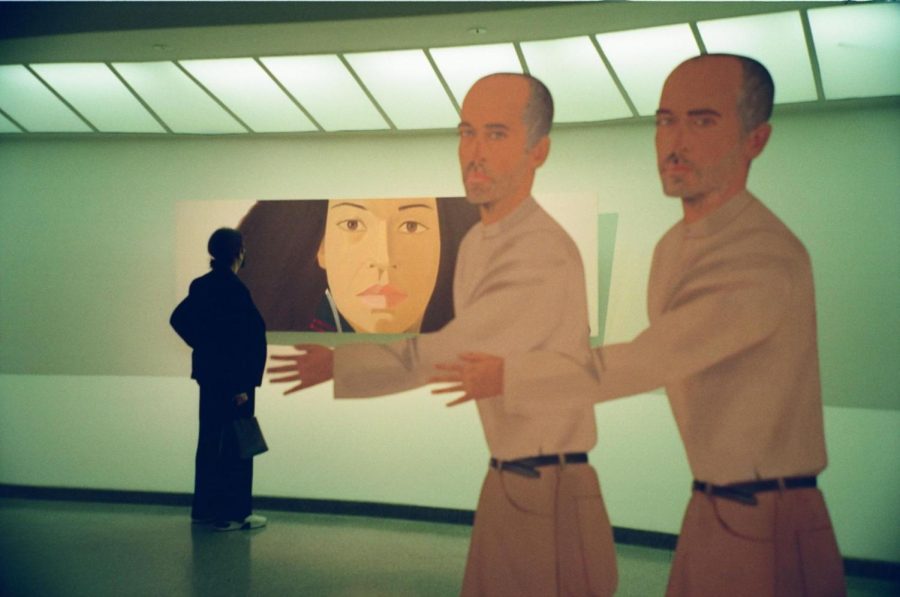

On a sunny weekday afternoon in November, I made a solo crosstown trip to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, a hallmark of the Upper East Side and the site of the newly opened, highly anticipated Alex Katz retrospective, “Gathering.” The crowd assembled between East 88th and 89th streets, packed onto a swath of sidewalk adjacent to the museum’s entrance, was substantial and notably diverse in age and dress. I was a small fish in a large pond of attendees; I observed bodies gathering by the bookstore entrance, shuffling mechanically through security, and finally dispersing into a dazzling, cavernous atrium. Once inside, I rode the elevator to the highest level and, armed with my Pentax camera, began my descent down, following the museum’s recommended route.

“Gathering” was on exhibition until Feb. 23 and commemorated American painter Alex Katz’s prolific, extensive career. Katz is a preeminent figure in the world of contemporary art, as well as a New Yorker committed to the faithful representation of his city’s inhabitants on the canvas. Born in Brooklyn and raised in Queens, he honed his “direct painting” technique at The Cooper Union in Manhattan as a young adult and graduated in 1949, after which he continued to paint New Yorkers and their environments.

His work is permeated by a distinct sense of immediacy and empiricism; Katz is interested in fleeting content, that which is momentary and observable. And while his subject matter ranges from flora to landscapes to portraiture, the undercurrent remains, in his words, “quick things passing.” Best known for his large scale portraits, including “Vivien in Black,” and “The Red Smile,” Katz has perfected flat planes, monochromatic backgrounds and cleanly articulated forms. It’s a singular technical style, idiosyncratic to the degree that the artist David Salle once wrote “a friend of mine … observed that you’d be able to recognize a Katz painting if it fell out of an airplane at 30,000 feet.”

In many ways, my circumstances reflected the most salient properties of a Katz painting, void of context but rich in visual cues, in strangers whose stories are, as I can only imagine, just as complex and vibrant as mine.

Exhibition highlights include “The Red Smile,” a minimalistic portrait of Katz’s wife that is at once seemingly effortless and visually engaging, and “The Cocktail Party,” a flashy, tightly composed rendering of its namesake. (Take the time to peruse the artist’s early sketches. They’re the demure underpinnings of his masterpieces.)

Some describe the retrospective as stark and unforgivingly cold. Others deem it stylish, simple yet effective. I’d call it honest.

It’s true that the artist’s pared-down sensibilities are polarizing, that the space his style occupies between abstraction and figural representation is inimitable and widely contested. But to me, it’s also startlingly provocative. In the halls of “Gathering,” I became the unsuspecting victim of an emotional ambush, caught off guard by a particularly resonant and personal viewing experience.

I’m no stranger to the Guggenheim, having visited several times as a child– it was a favorite museum of mine. I suspect this sentiment is due in large part to its nonconformist design, the focal point of which is a concentric ramp guiding viewers through descending exhibition spaces.

Yet as I made my way through the Guggenheim’s labyrinthine galleries this past month, I felt as though I were visiting for the very first time. It was as if I’d never experienced the sort of communal gathering in front of a painting that should have felt so familiar but instead seemed quite new. I rationalized the peculiar sensation as an acute spatial awareness, or otherwise an abnormally strong response to Katz’s works. (The latter checked out: I’m one to cry at artwork.) But in truth, I was reckoning with a novel and unforeseen challenge in my life away from home: looking at art alone.

Surrounded by a crowd of unfamiliar faces and confronted by Katz’s candid portraits, which offer a viewer very little context and thus create an air of anonymity around their subjects, I thought deeply about what it means to be anonymous – to be alone. I realized that in the eyes of my neighbor, I am as much a stranger as the individuals Katz renders on his canvases. It was not an unpleasant observation. I wasn’t upset by the notion that my story is not immediately evident to the people with whom I cross paths momentarily, in those fleeting instances on the subway or in the line for security to enter the museum or in front of Katz’s sketches in the Guggenheim. I was merely moved by the unassuming reminder that for the first time in my life, I was in a silent dialogue with the subjects of Katz’s portraits and my fellow museumgoers — instead of with my mom.

My mom took me to my first museum when I was just 11 days old. Together, we frequented the Addison Gallery, an academic museum on the campus of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, when I was young. A former art history student and visual artist, my mom had worked at the Addison for some time before I was born. It was a job that she described to me as deeply fulfilling and, on some memorable days, thrilling for an art lover like her. Our home was filled with art and books, which I pored over intently; by the age of 10, I could identify a Giacometti, a Sol Lewitt or a Louise Bourgeois. My mom encouraged my sister and I to look patiently, think deeply and create often. Some of my most evocative childhood memories are set in galleries: the Addison, the Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim.

For the greater part of my life, I always visited museums alongside my mother. I came to anticipate the familiar refrain of my mom’s inquiries when I stood before an artwork: “What do you see? How does it make you feel?” These are simplified versions of the guiding questions used in visual analysis, a tenet of the study of art history. I did not know it at the time, but she was training me to look thoughtfully, a skill I cherish. Maybe our dialogues matured as time passed, and perhaps my analyses became more nuanced with age, but the essence of our conversations remained: What do you see? How does it make you feel?

So as I wandered through “Gathering,” packed side by side with individuals conversing in their own distinct ways with the same collection of artworks as I, those familiar questions stirred: What do you see? How does it make you feel? I was alone in a sense, but never without a partner in conversation, be it my mom or the painting in view. And though my neighbors appeared to be perfect strangers, as I was to them, we shared a unique and intimate moment in passing, drawn together, if only briefly, by Katz’s work. He was, and stubbornly continues to be, an artist fervently interested in the “emotional resonances of his human subjects,” in the representation of the individuals in his direct orbit. In many ways, my circumstances reflected the most salient properties of a Katz painting, void of context but rich in visual cues, in strangers whose stories are, as I can only imagine, just as complex and vibrant as mine.

I stood before the Guggenheim’s hallowed walls and saw the paintings through a dual lens: firstly through my own eyes, and then through those of my mom, who taught me how to look. Now, as I look in a new stage of life, my perception is framed by solitude and pockets of intimacy amongst the anonymity. To view art is to engage in a dialogue — and though the conversation’s participants might change, we are always the constant variable. Whether you find Katz’s works resonant or dissonant, there’s beauty in the conversation.