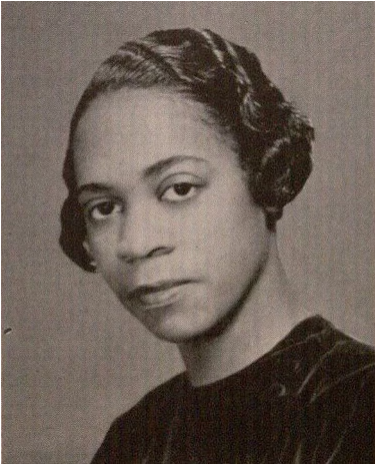

Remembering the Legacy of Marie Clark Taylor, Ph.D., a Trailblazing Female Botanist of Color

The first woman to earn a science Ph.D. at Fordham in 1941 was also the first ever Black woman to earn a degree in botany

COURTESY OF FORDHAM LIBRARIES

Dr. Marie Clark Taylor, pictured in the 1941 Fordham yearbook, paved to way for Black women in science.

December 8, 2021

Among the countless alumni who have earned a degree at Fordham University in its long history, Marie Clark Taylor stands out for a variety of reasons. Taylor became the first Black woman to ever earn a science degree at Fordham, receiving her Ph.D. in botany at the university’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) in 1941. She became the first woman of color to ever hold such a degree in the field of botany.

Life Before the Ph.D.

Marie Clark Taylor was born Marie B. Clark on Feb. 16, 1911 in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. After graduating from Dunbar High School in 1929, Taylor enrolled at Howard University, a historically Black college in Washington, D.C. Taylor’s passion and curiosity for botany earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the subject in 1933 and 1935, respectively.

Taylor remained in D.C. for a few years after graduating from Howard. She became a high school science teacher at Cardozo High School, where she incorporated her knowledge of botany into her biology classes. Desiring to expand her knowledge while continuing to teach at Cardozo, she enrolled at Fordham to earn her Ph.D. in 1938.

Light and Flowers

Fascinated by photosynthesis cycles and their effects on budding flowers, Taylor wrote her dissertation for her Ph.D. on the topic. Her doctoral dissertation, titled “The Influence of Definitive Photoperiods Upon the Growth and Development of Initiated Floral Primordia,” involved the study of varying periods of light and its effects on the primordium, the buds from which flowers grow from the stem.

Taylor designed a series of experiments using three different flower species in order to “discover the influence of definite photoperiods of six, ten, and sixteen hours upon the inflorescences that develop from floral primordia exposed to these photoperiods.”

Taylor exposed different flowering plants to varying durations of light to test light’s influence on the plants’ flower growth rate. Taylor used the species Salvia splendens (scarlet sage), Cosmos bipinnatus (garden cosmos) and Cosmos sulphureus (orange cosmos) for her experiment.

Curious about the different effects that artificial light may have on plants as opposed to natural sunlight, Taylor subjected each of the plants to three different “photoperiods” where the plants received natural sunlight, supplemented in the last six hours of the 16-hour experiment with artificial light.

Marie Clark, Ph.D. became the first woman to ever receive a science doctorate from GSAS.

Taylor found that the scarlet sage bore flowers ideally under 10 hours, while 16 hours stunted its rate of growth at a similar rate to that of the six-hour trial. The two cosmos plants were found to have a linear relation between their growth rates and length of their photoperiod; the longer the cosmos plant was exposed to sunlight, the more it would grow and flower.

Taylor noted how “Anomalous heads appeared in those inflorescences developed during the sixteen-hour photoperiod,” suggesting that cosmos plants are most adapted to around 10 hours of sunlight.

Life After Fordham

With her dissertation accepted in 1941, the newly titled Marie Clark, Ph.D. became the first woman to ever receive a science doctorate from GSAS, graduating cum laude.

Taylor wasted no time basking in her accomplishments, joining the Army Red Cross during the height of World War II. While stationed in New Guinea, she met Richard Taylor, an infantryman for the all-Black 93rd Airborne division. They married in 1948.

After the war, she returned to Howard as an assistant botany professor. Taylor remained a notable professor there and she founded its first botanical greenhouse laboratory. When she gave birth to her son in the summer of 1950, her students joked that she had planned the birth in advance to not coincide with final exams. She remained chair of Howard’s botany department until her retirement in 1976.

Besides her work at Howard, Taylor continued to teach biology to young students. She developed and implemented hands-on experiments for her students, sharing them with her fellow professors across the nation. Throughout the 1950s, Taylor expanded her role via summer science institutes which she proctored for high schoolers. President Lyndon B. Johnson even acknowledged Taylor’s accomplishments and personally encouraged her to share them abroad in the 1960s.

Taylor passed on Dec. 28, 1990, at the age of 79. Howard University named a scholarship program after her, as well as an auditorium in Howard’s biology department hall. Taylor’s legacy extends beyond her scholastic achievements, and she is widely cited as the woman who brought interactive tools like light microscopes to biology and botany students worldwide. The Fordham community remembers Taylor as a groundbreaking graduate student who overcame the obstacles associated with her race and gender, ultimately triumphing.