COVID-19 isn’t the only pandemic the Fordham community has lived through. Over the past 100 years, the international community has faced different infectious diseases that disturbed our sense of normalcy. From the early 1900s to present day, each pandemic was unique in regard to the type of pathogen circulating and the subsequent public health response.

COVID-19 isn’t the only pandemic the Fordham community has lived through. Over the past 100 years, the international community has faced different infectious diseases that disturbed our sense of normalcy. From the early 1900s to present day, each pandemic was unique in regard to the type of pathogen circulating and the subsequent public health response.

While facing each virus head-on, researchers and government officials developed protocols and treatment plans that would later prepare them for future pandemics. This list of pandemics highlights how the Fordham community responded to each event in history.

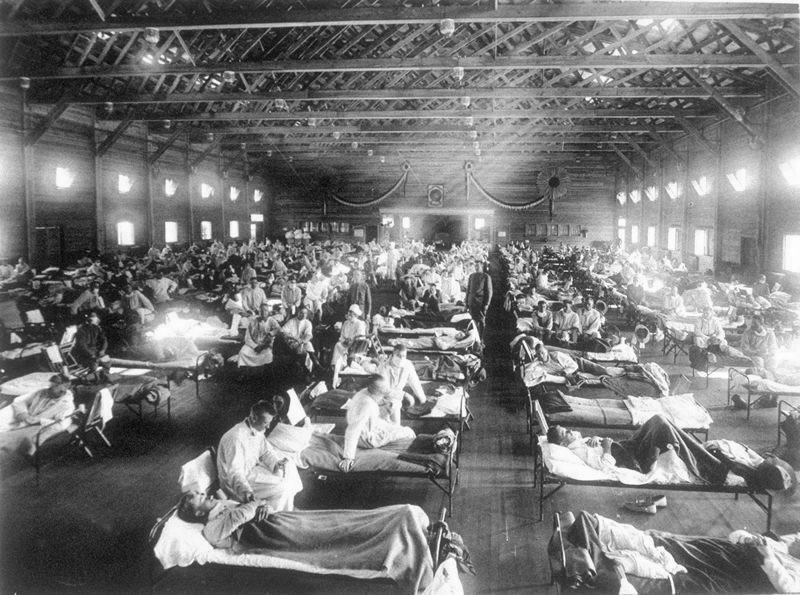

Spanish Flu Pandemic: 1918-1920

The dean of Fordham’s now-defunct medical school prescribed “rest, alcohol, simple diet, and the free use of mustard plasters and hot mustard footbaths” as a regimen to protect oneself against infection.

In the early 20th century, the 1918 H1N1 virus, also known as “the Spanish flu,” swept across the planet, infecting about one-third of the world’s population. The flu claimed the lives of over 50 million people globally and 675,000 in the United States, including 20,000 New Yorkers. This number is comparable to the 26,000 New Yorkers who lost their lives in the COVID-19 pandemic so far.

The 1918 H1N1 virus was incorrectly named the “Spanish flu” as it did not originate in Spain. During the first World War, Spain was a neutral entity. The free press in Spain consistently released information about the growing number of cases there. Other nations, however, did not provide accurate case counts among their populations. Because Spain was publishing the first recorded cases, many believed that the virus originated there and subsequently called it the Spanish flu.

The 1918 H1N1 had a high mortality rate among children under five, healthy adults between 20-40 years of age and the elderly. Initially, the flu made its way through soldier populations on battlefields across Europe because of malnutrition, lack of hygiene and cramped conditions. The virus affected both the upper and lower respiratory tract of those who were infected, making it highly contagious and often lethal.

The first wave of the pandemic was relatively innocuous. It was the second wave that claimed the majority of the lives lost. The efforts to contain the virus were through nonpharmaceutical interventions. Officials imposed limits on public gatherings, increased quarantine efforts and encouraged good personal hygiene and the use of disinfectants. Moreover, infected patients were forced into self-isolation.

Although many of these precautions were effective, the pandemic revealed that the public, and even some physicians, did not know much about infectious diseases. For example, in 1918, the dean of Fordham’s now-defunct Medical School prescribed “rest, alcohol, simple diet, and the free use of mustard plasters and hot mustard footbaths” as a regimen to protect oneself against infection.

During the summer of 1919, people began to build an immunity to the flu. Though the rate of infection decreased, the legacy of the pandemic remains today. Over the next few decades, many studies surrounding the 1918 H1N1 virus were conducted. The virus was sequenced and reconstructed in laboratory settings in order to help humans deal with future pandemics.

AIDS Pandemic: 1981-present

In West Africa during the 1920s, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) developed in a chimpanzee and was transferred to humans. HIV is the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Toward the end of the 20 century, the virus spread across the globe. Currently, around 40 million people are living with HIV.

In 1982, 335 people in the U.S. were infected with HIV, and 136 were killed by AIDS. Initially, the virus was called “gay-related immune deficiency” because public health officials believed gay men were the most susceptible to it. The virus was known as the “gay plague,” although people were affected regardless of their sexual orientation or gender. Because of the stigmatization and unfounded fear of only gay men spreading the virus, the FDA enacted regulations that banned them from donating blood.

In a 1988 piece in The Fordham Observer, Stephen Shafer vehemently critiqued the administration’s denial of responsibility to provide a sexual education for students.

In 1984, researchers figured out that the cause of AIDS was HIV. By 1985, there were over 20,000 cases globally. In 1987, AZT, the first antiretroviral medication for HIV, was developed. By the end of the ’80s, there were 100,000 cases of AIDS in the U.S. and over 400,000 cases worldwide.

According to a 1987 issue of The Fordham Ram, Margaret McQuillian, the director of the University Health Center, said, “We, as a private institution in the Jesuit tradition, here more or less follow along with the Catholic Church’s finding on no pre-marital sex, and no extra-marital sex.”

McQuillian further explained that every person has the right to act in whatever way they are inclined. “If you are sexually active it is very important that you be aware of the dangers that come with that and that you take the proper precautions to protect yourself,” she continued.

Students on both campuses had contradictory views on the Fordham administration’s response to the crisis. In a 1988 piece in The Fordham Observer, Stephen Shafer vehemently critiqued the administration’s denial of responsibility to provide a sexual education for students. He cited the Fordham Residential Life Handbook which stated that the Catholic Church “mandates that sexual intercourse be reserved for marriage.”

In the past few decades, researchers developed more treatment options and medications for the disease. Compliance with this therapy can reduce the rate of transmission from mother to child and partner to partner. In the ’90s, cases began to decline globally after widespread medical intervention. Currently, 64% of people with the virus live in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2005, Cynthia Poindexter, associate professor at Fordham University’s Graduate School of Social Service, emphasized that in the U.S., the number of women infected rose significantly. This was primarily among Black and Latinx women, who, combined, constitute 80% of all women with AIDS in the U.S. even though they comprise only a quarter of the female population. It is crucial to increase research for treatment options and address these disparities.

H1N1 Swine Flu Pandemic: 2009-2010

Lincoln Center saw 12 cases of H1N1, whereas the majority, totaling 165, were at Rose Hill.

In late spring of 2009, a novel influenza virus emerged in the United States. This virus, which scientists called (H1N1) pdm09, infected 60.8 million people, sent 274,304 individuals to the hospital and claimed 12,469 deaths in America alone. Nevertheless, by Aug. 10, 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the pandemic had finally come to an end.

Since the virus had genes similar to influenza viruses known to infect pigs, scientists started referring to it as “swine flu” early on in the pandemic. Like the current coronavirus, humans came into contact with the H1N1 virus through exposure to animals, and in the case of H1N1, pigs were to blame.

Though the NYC Department of Health (NYCDOH) noted cases of H1N1 as early as April 23, 2009, the case count amounted to 1,666 during the first wave, which took place from April to June of 2009. Two waves followed, one in the summer of 2009 and another from Oct. 2009 to March 2010.

H1N1 made its way to Fordham in the fall of 2009. Lincoln Center saw 12 cases of H1N1, whereas the majority, totaling 165, were at Rose Hill.

In Oct. 2009, Marc Girard, Fordham College at Lincoln Center ’10, possibly contracted H1N1 and had to quarantine in an empty three-bedroom suite on the 19th floor of McMahon Hall. With a 104-degree Fahrenheit fever at the beginning of the quarantine, Girard stayed in isolation until he was fever-free for 24 hours.

Students at Fordham exhibited a fair amount of vaccine hesitancy toward the H1N1 vaccine. By the end of the fall semester in 2009, University Health Services had a surplus of 300 H1N1 vaccines.

Keith Eldredge, the dean of students at Fordham College Lincoln Center at the time, sought first to isolate infected students from the rest of the student body. Eldredge expressed reservations about closing campus even if a large outbreak were to take place. In that event, the dean planned to relocate sick students to Pope Auditorium.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the H1N1 vaccine on Sept. 15, 2009, and Fordham received 1,000 doses to allocate to its students in November. University Health Services made these vaccines available to students on a first-come, first-serve basis with a $15 co-pay.

Students at Fordham exhibited a fair amount of vaccine hesitancy toward the H1N1 vaccine. By the end of the fall semester in 2009, University Health Services had a surplus of 300 H1N1 vaccines. Young people were the target demographic for the vaccine due to their high susceptibility to getting sick, yet several Fordham students cited “common sense” practices like handwashing and staying home while sick as sufficient ways to stop the spread of H1N1.

Coronavirus Pandemic: 2020-Present

On Jan. 9, 2020, the WHO announced the spread of a pneumonia-like illness among residents of Wuhan, China. At that time, there were only 59 reported cases. The disease later became known as COVID-19, and the extent of its spread reached pandemic status by March 11.

New York became the epicenter of the pandemic by March, and on March 9, University President Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., announced that classes would cease meeting in person until March 30. Classes would meet virtually starting the following Wednesday, and McShane encouraged students living in residence halls to return home early for spring break.

The plan to return to face-to-face instruction on the 30th was short-lived as McShane issued an email on Friday, March 13, stating that classes would remain online for the remainder of the semester. McShane ordered resident students to leave campus “as quickly as they can.” On March 19, the first cases of the virus were confirmed on campus.

On March 20, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order that closed nonessential businesses and nonprofit institutions, which would go into effect at 8 p.m. that Sunday, March 22. This policy restricted students from returning to campus to retrieve their belongings from the dorms.

By April, COVID-19 cases peaked in New York City, and the case count slowly dropped as the summer months rolled around.

The administration postponed spring 2021 classes until Feb. 1 in anticipation of the winter spike in cases. The vaccine remains largely unavailable to members of the Fordham community.

As New York state started to open in response to the decreasing number of cases, Fordham offered its students three modalities to learn in the coming semester: McShane announced on July 20 that students could choose to “learn fully online, in person, or a hybrid combination of the two.”

Students returning to campus must complete a daily questionnaire on VitalCheck and get tested four times throughout the semester. The administration also ordered students entering residence halls to quarantine prior to returning to campus.

Over the course of the fall semester, phase three clinical trials successfully produced two viable vaccines. On Nov. 9, Pfizer announced that its vaccine was 90% effective in preventing COVID-19 infection in its clinical trials; a week later, Moderna announced that its vaccine was 95% effective.

Both vaccines eventually became available via an Emergency Use Authorization through the Food and Drug Administration, but as supplies remain limited, only certain groups, including people aged 65 and older or essential workers, can get vaccinated.

The administration postponed spring 2021 classes until Feb. 1 in anticipation of the winter spike in cases. The vaccine remains largely unavailable to members of the Fordham community.

Though the ultimate endpoint of this pandemic is still in the future, COVID-19 isn’t the first virus Fordham and, more broadly, New York has weathered through. Adherence to public health guidance while also remaining hopeful and tenacious will ensure that we see the end of COVID-19.

COVID-19 isn’t the only pandemic the Fordham community has lived through. Over the past 100 years, the international community has faced different infectious diseases that disturbed our sense of normalcy. From the early 1900s to present day, each pandemic was unique in regard to the type of pathogen circulating and the subsequent public health response.

COVID-19 isn’t the only pandemic the Fordham community has lived through. Over the past 100 years, the international community has faced different infectious diseases that disturbed our sense of normalcy. From the early 1900s to present day, each pandemic was unique in regard to the type of pathogen circulating and the subsequent public health response.