A Few of God’s Marines

Coping With Diminished Jesuit Presence on Campus

COURTESY OF RYAN BRENIZER/FORDHAM UNIVERSITY

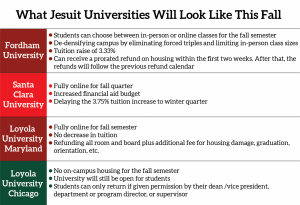

In 1983, Jesuits held all of the presidential positions in the country’s Jesuit universities; today they hold less than half.

November 29, 2020

It’s hard for me not to admire our president, the Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J. A combination of authority and distance adds to the mythos of any man. In veneration, McShane becomes a watchful shepherd, perched high above a herd of Fordham Rams, staff in hand, vigilantly watching the dark forest for wolves.

Being a university president is extremely difficult, and there’s something Promethean about McShane. If anyone was going to take fire from heaven it just seems like it would be him. He’s a Jesuit, after all — one of “God’s marines.” But what if he’s the last?

Mentor Sally Benner, Fordham College at Rose Hill ’84, remarked that the future of Jesuits at Fordham was uncertain because their numbers were decreasing. “There just aren’t that many men who have gone into the order,” she said, “and of those who do, a lot don’t want to be university presidents.”

“There are fewer Jesuits interested in being university administrators.”Rev. Thomas Massaro, S.J.

Rev. Thomas Massaro, S.J., who lives in Spellman Hall at the Rose Hill campus, said that when he joined the Jesuits in 1983, all 28 Jesuit schools across the U.S. had Jesuit presidents. Since then, according to Massaro, Jesuits have gone from holding every presidential position throughout America’s Jesuit universities to less than half.

“There are fewer Jesuits interested in being university administrators, and, to tell you the truth, I fit that category,” Massaro said.

Hunting for Answers

An article by The Washington Post described Jesuits bracing “for near-extinction in this part of the world.” I assumed, wrongly, that talking to Jesuits would provide an authoritative answer on why there were fewer of them. Is it the lure of financial success and family life that draws young men away from the priesthood? Those temptations are as old as time, so it must be something more.

Perhaps a religion 2,000 years old is beginning to show its age.

The Suppression of the Jesuits from 1773 to 1814 reflected a systemic and targeted campaign of elimination. There were clear animosities; antagonists were visible; the devil was apparent. Today, in the absence of explicit suppression, there is no visible adversary. Potential Jesuits seem to be drawn away by osmosis. Whether this rises from forces of modernity or secular pressure remains unclear. Perhaps a religion 2,000 years old is beginning to show its age. Perhaps young people see religion as antiquated, inflexible and uncool.

What Matters is God’s Will, Not Ours

Current Jesuits do not respond to the shift with alarm, but rather with calm expressions of faith. Take the Rev. Michael McCarthy, S.J., who resides with Massaro, McShane and other Jesuits at Fordham’s Spellman Hall.

When I told McCarthy that his fellow Jesuits did not express “desperation or urgency” regarding their declining numbers, he said he identified with some of the words I had used, but not others.

“Ultimately, what we are about is God’s will, and that God’s will is done. Not ours.”Rev. Michael McCarthy, S.J.

“Desperation? No. Urgency? Yeah. I think that our lives and jobs are always urgent. In this moment of history, the basic tenets and goals of Jesuit education have never been more urgent,” McCarthy said. “Ultimately, what we are about is God’s will, and that God’s will is done. Not ours.”

McCarthy said he was more concerned with the impact of Jesuit work than their numbers. It didn’t matter all that much to McCarthy whether there were many Jesuits or few. “What does matter is that the work of God’s purpose for the good of the world does progress and ultimately prevail — that is where I place my hope. Not in whether there is an increasing or declining number of Jesuits.”

Priests, like all religious leaders, are spiritual first responders. They wouldn’t make popular pessimists. Religion didn’t become trendy by bumming people out. Not one priest ever contradicted his brother. There may be fewer of them, but their unity is not lessened, nor their faith, nor their conviction.

Another of Fordham’s resident Jesuits, the Rev. Thomas Regan, S.J., said, “We’re very much a team, we live as a community, and we see our work at Fordham as a group effort.” He explained that some of the most Jesuit people are not Jesuit, Catholic or even Christian. Regan mentions former provost Stephen Freedman, a Jewish man whom he describes as “one of the most Jesuit people I’ve ever met.” Regan explained the Jesuits are “not a closed club in which only Catholics or only Jesuits can play, anyone who buys into the mission (can participate) … if you understand what the mission is, you can be a big supporter.”

Men in Motion

Jesuits are not designed to stay in one place. Like an Italian automobile, they are made to move. It’s how they are trained to operate. Movement is built into the design.

Massaro quoted a well-known Jesuit slogan, “Our true home is the road,” explaining, “A Jesuit should not literally always be on the road but, in a sense, moving, looking out for where the greatest need is: pastoral needs, intellectual needs and especially spiritual needs, because we’re intended to help people with their spiritual lives.”

A stable life in America, free of danger and adventure, may do more to harm the Jesuit brand than open hostility.

Massaro explained the Jesuit calling is to help a large variety rather than select groups of people. “Being at Fordham seems a little bit static,” he said.

It’s hard to form lasting relationships as a university administrator or professor. Students graduate and move on. Careers pull students out into the world as teachers stay behind and watch. Being tied to a university limits Jesuits from attending to the spiritual crises that occur after graduation, in what we vaguely refer to as “the real world.”

Entrenched Success

Jesuits, like Marines, are usually “first on the beaches.” That’s the historic mentality of these men, painstakingly educated, fashioned like statues from stone. Jesuits have always been first to land in non-Christian countries, sometimes hostile ones. Like Marines, Jesuits have frequently been first to die in pursuit of their mission. It may be that the weakness of Jesuit society is its strength. The danger is security. Perhaps that is why their numbers have dwindled as the iron curtain crumbled. Totalitarian regimes intolerant of religious expression may have encouraged recruitment. Antagonists keep movements vital.

Despite being neither Catholic nor Jesuit, the power of that simple mission speaks to me.

A stable life in America, free of danger and adventure, may do more to harm the Jesuit brand than open hostility. Nothing is more vulnerable than entrenched success.

Bob Howe, assistant vice president for communications and special adviser to the president, wrote that “the number of Jesuits at Fordham has declined in tandem with the number of Jesuits in the United States and around the globe.” Perhaps, instead of a global decline, the society’s major centers of recruitment are only shifting to those parts of the world where Christianity is still a minority religion, and the Jesuit purpose still seems vital in the face of persecution.

Foreign Frontiers

When Massaro entered the Society of Jesus in 1983, the U.S. had the most Jesuits in the world, around 7,000. As of 2020, the number is less than 2,500. As American Jesuits have dwindled, the number of Jesuits in India has dramatically increased. Most of today’s Jesuits are rising in South Asia and India. There is also activity in Africa.

When Massaro was at Fordham in the 1980s as a graduate student, there were 100 active Jesuits serving the campus. Now he finds only about 28 at Rose Hill. “The next question is whether that is threatening to our mission. Our mission is to help Fordham to thrive, to keep its identity, its Catholic Jesuit education, but intended for all people,” Massaro said. Ultimately, Massaro came to the same conclusion as McCarthy — the Catholic Jesuit purpose doesn’t require massive numbers of Jesuits to fulfill.

And it’s hard for me not to support that purpose. Despite being neither Catholic nor Jesuit, the power of that simple mission speaks to me. Every college, regardless of affiliation, wants to tell its students they are being set up to go out into the world and set it on fire. That’s the fundamental Jesuit undertaking — leader-building. I expressed this to Regan.

Flash Forward to General Decline

“Flash forward several generations — I never got excited when we started talking about the numbers of Jesuits,” Regan told me in a frank Bostonian manner. He explains how St. Ignatius would use groups of five to six Jesuits to start schools in faraway countries, essentially from scratch. Talk about power in numbers.

Prior to the late ’80s, it was common for U.S. Jesuit universities to have nearly 100 Jesuits on their campuses, with provinces taking in 30-50 new Jesuits a year. “Now, instead of lamenting our numbers are lower, I think we’re getting back to homeostasis,” said Regan.

The light of Jesuit ethos was never dwindling, it was merely passed onto us.

He references a “general decline of religious practice in Europe” which has “spilled over into the U.S.” without exactly pinpointing the cause of that drop. Perhaps the strength and security of the Roman Catholic Church in Europe and America has detracted from the glory of its advance guard. At least during the suppression, Jesuits were broadly relevant.

I recalled asking Massaro about the survival of the Jesuit mission. He said, “I like to think we’re still succeeding and that we’re relying upon our colleagues … to do their job, to reflect our mission. They’re not going to be exactly the same as us Jesuits, but we’re relying on their similar values … so yes: It’s a new model where we don’t control the university, but we try to inspire it, or animate it. That’s our model today.”

The light of Jesuit ethos was never dwindling, it was merely passed onto us. As custodians of their flame, it is our mission to bring it with us and use it to set the world on fire.

Correction: A previous version of this article listed incorrect dates for the Suppression of the Jesuits. The article has been updated to reflect the correct information.

john walton • Dec 4, 2020 at 8:57 pm

The suppression of the Jesuits commencing in 1773 was in some part owing to financial improprieties!

My wife (TMC’71) and I (FCRH’72) have had warm and enduring relationships with many Jebbies, but ol’ Chronos is catching up. I will never forget Fr. Richard Doyle SJ, Chair of the Classics Department, hurling a piece of chalk at a FCRH’74 classmate seated and sleeping in the last row of a classroom in Keating! Doyle nailed the miscreant squarely in the forehead with the chalk. Doyle also officiated at our marriage ceremony!