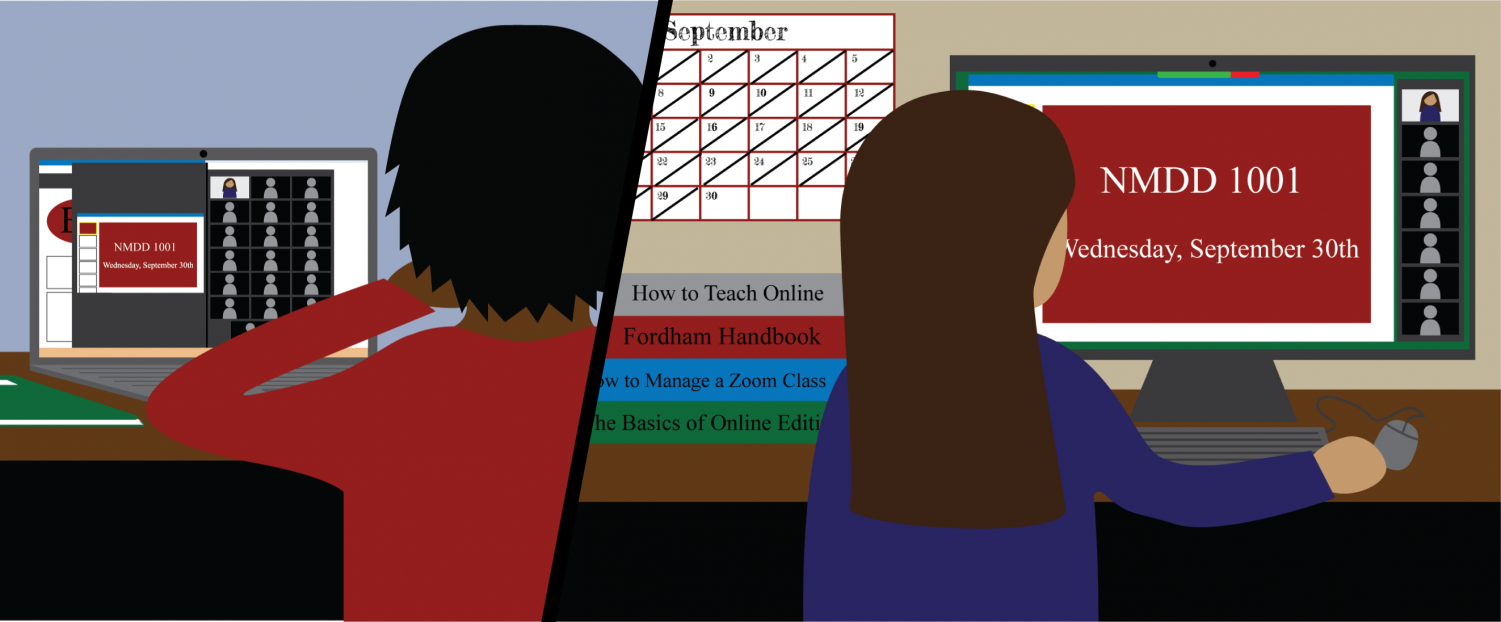

Two months into the fall 2020 semester and students are still adjusting to the new normal sparked by the coronavirus and the shift to digital learning. Students say they are facing heavier workloads and more screen time — a stark contrast to the latter half of the spring 2020 semester.

Over the summer, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) Dean Laura Auricchio and Fordham College at Rose Hill Dean Maura Mast co-chaired a working group with instructors to plan for online courses. The group was formed in response to student concerns about “a notable reduction in the quality of our education” in the spring semester.

Auricchio said neither she nor Mast anticipated the increase in workload for students and instructors this semester, as it was not a problem in the spring, but they also did not want students to “feel cheated” out of up-to-par coursework.

“We wanted to provide a substantive education. I am afraid that we might have gone too far,” Auricchio said.

Students and Instructors Acclimate to Greater Workload

I’ve never had to study this much or do so much classwork in my in-person classes and the combination of the extra workload, an internship and regular work can get crazy at times. Samantha Rizzo, FCLC ’22

Diana Silva, FCLC ’23, said she has professors who are working hard to adapt classes while others don’t “notice how much work they are giving us.”

“I legit spend all week doing schoolwork,” she said. “Since the workload has increased, all I do is schoolwork and work. It’s a bit heavy on mental health to be honest and I wish it wasn’t so much. I don’t even have my own personal downtime like I used to.”

Samantha Rizzo, FCLC ’22, agreed that the workload this semester is greater than usual. She said classes with a concentration on asynchronous components tend to have more assignments and larger time commitments.

The increase in labor-intensive work is not only occurring for students but for instructors as well. “It is 10 times as much work,” Shiloh Whitney, professor of philosophy, said when comparing her current workload to a traditional semester. “It takes a massive amount of preparation.”

An ongoing course called Flex1000 on teaching in a hybrid environment is available to all instructors. The course covers technical issues and how to build community digitally. Anne Fernald, special adviser to the provost on faculty development, and Steven D’Agustino, director of online learning, lead the course twice a week.

Whitney was one of the few hundred instructors who took the course: “There was a huge challenge to meet a sudden and more massive demand for access and resources and that absolutely didn’t go perfect, but there was also a lot of hard work done.”

Leo Guardado, professor of theology, described the process of teaching virtually as “much more work.” He now has to create his presentations, produce one full recording without interruptions, edit and rewatch the lectures, upload the videos and finally email his students the information.

“All of those steps take up to four hours just to create a 20-minute video; it’s hours of preparation and hours of rereading content. It is a whole new level of preparation,” Guardado said.

“Translating an activity online requires a lot more imagination in creating experiences for learning,” Professor Diane Detournay, a lecturer of English, women’s studies and American studies, said. “The labor becomes more time-consuming. It is radically different. It is a different type of work, so it feels intensified because of being in front of a screen 12 hours a day.”

Rizzo also said she spends most of her day on the computer for class, homework and her remote internship. Her “break” is when she goes to work in-person at a local mall. “I’ve never had to study this much or do so much classwork in my in-person classes and the combination of the extra workload, an internship and regular work can get crazy at times.”

In response to students’ reactions about the reality of the fall semester, the Office of Institutional Research concluded an optional survey on Sept. 25, inquiring about students’ experiences.

“The No. 1 takeaway from the survey for me is that the work is much greater than anticipated,” Auricchio said. In response, she is collaborating with Mast to help “course correct.”

A Shift in Time Commitment

The whole semester is a pedagogical experiment, like throwing spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks. Leo Guardado, professor of theology

Since the spring semester, Whitney cut down to leading only one live session a week per section and Guardado broke up his class into three groups of 12, who all attend class for 30 minutes twice a week.

“The whole semester is a pedagogical experiment, like throwing spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks,” Guardado said.

Guardado said his students are doing the same amount of work as they would be doing in person, as he has created shorter assignments with more creative opportunities.

Whitney developed her course to have nine hours’ worth of work each week for her students. Whitney also said she designed her course so that both she and her students have weekends off from work.

“I wanted to make a course that is challenging for students, so they get to learn something meaningful and be proud of themselves,” Whitney said. “It is important for courses to be challenging, but the workload must be reasonable.”

According to Fordham registration information, a traditional upper-level class entails two hours and 30 minutes per week of formal instruction, plus an additional three hours of preparation work, totaling an average of five hours and 30 minutes of work per class a week.

Fordham has to legally meet the criteria of both the New York State Education Department (NYSED) and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education when planning the amount of time students engage in instruction and additional classwork.

For the 2020-21 academic year, the NYSED did not change the requirement of at least 15 hours of instruction and at least 30 hours of supplementary assignments per semester. The Middle States Commission requires “regular and substantive interaction” for distanced learning. Neither of the institutions set a maximum for coursework or instruction, only minimums.

“At times it feels like I’m doing way more work, and it’s not the professors’ fault but really just the online format, because we have to spend extra time doing what we would have been doing in an in-person classroom setting,” Ali Bernstein, FCLC ’22, said.

“In addition to the type of homework that would normally be assigned, we’re also watching a class-length video lecture and meeting for Zoom discussion or doing blackboard discussion assignments in lieu of a dynamic in-person classroom discussion.”

Bernstein said she can visibly notice her fatigue from everyday life activity being converted to screen time for class, homework and clubs.

“I got a job thinking I could manage both because last semester wasn’t too bad,” Silva said. “It was manageable. But then professors started giving so much work, and I don’t think they understand that we don’t just sit at home and do nothing all day and wait for class. We have other things and extracurriculars in the mix as well.”

Impact on Learning Experience, Job Responsibilities and Finances

I find myself having to do a lot of carework for friends and others. All of the labor required for that gets no recognition. It makes the idea of balance difficult. Diane Detournay, lecturer of English, women’s studies and American studies

The abrupt shift to online courses in the spring led to grace-giving accommodations being implemented, such as the option for students to elect to receive a pass/fail grade for any class and instructor lenience on attending live sessions from across the globe.

“It was a scramble; we were operating in crisis mode, but there is a possibility of a more vibrant online experience now,” Detournay said when comparing the two semesters.

An emphasis on curriculum has led to many losing sight of the fact that the global turmoil is deeply impacting everyone, according to Detournay. “I find myself having to do a lot of carework for friends and others. All of the labor required for that gets no recognition. It makes the idea of balance difficult.”

Over 280 Fordham employees signed a statement on carework in August, asking the university to acknowledge the burden it places on instructors.

In addition to responsibilities outside work, Whitney said that the move to online teaching created complications in fulfilling her professional responsibilities.

“Teaching is a third of the job and it takes half of your time during the school year, so the summer is important for the other elements,” she said in reference to tenured professors also having to complete research and service requirements. “I think I and a lot of people lost the summer for the research part of the job. It is a problem for people still on the tenure-track.”

She said the online form of education prompted new financial stressors as well. “Permanent faculty have had our pay frozen by the university (so no raises even for inflation), and now the administration is pushing to take away the university’s retirement contributions too.”

Whitney said the changes feel demoralizing. “We’re working harder than we ever have, and on top of that, we’re being asked to shoulder the burden of cost-cutting measures,” she said.

Detournay is a fifth-year lecturer and part of Fordham’s contingent faculty.

“We are unionized and have collective bargaining rights, which is so critical during these times,” Detournay said. “I think there has not been enough recognition on the part of the institution that what appears to be small cuts to salaries or benefits have huge life consequences. If you are already living on the brink, any cut can be devastating.”

Planning for the 2021 Spring Semester

Looking ahead for plans in the spring — assuming that in-person classes will be a possibility — Auricchio said grappling with a mixture of online and in-person students will be another challenge. A possible solution would be offering two sections of a class at the same time, one being online and one being in-person, she said.

If tasked with making course decisions in 2021 similar to those made this fall, Guardado said he would only return to teaching in-person if he was allowed to conduct it with a full class. Since the hybrid model is “twice as much work” to accommodate two groups of students, Guardado would elect to keep his entire class fully online if going fully in-person is not a possibility.

Auricchio said she is committed to finding solutions for students: “If we don’t know about a problem, we can’t fix it. There is nothing we want to do more than to help.”