Sex, Lies and Videotape: New Eliot Spitzer Documentary Rises and Falls

In “Client 9,” Director Alex Gibney Suggests a Scandal Beneath a Political Scandal

July 23, 2011

Published: November 03, 2010

Coming to theaters three days after election day, writer, director, and co-producer Alex Gibney reexamines recent political history in his latest documentary, “Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer.” As the title suggests, Gibney sifts through the background, proceedings and aftermath of the New York Times’ scandalous March 2008 revelation that Eliot Spitzer paid prostitutes for sex while serving as governor of New York.

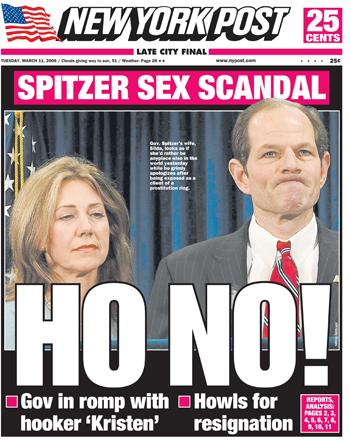

As the makings of the scandal are reconstructed, Gibney suggests that political motives likely lie buried beneath the seemingly cut-and-dry prostitution case. The nature of the federal investigation, which resulted in Spitzer’s resignation from office and the way the media sold the story to the public (from “Sheriff of Wall Street” to “Luv Gov”) are all the evidence Gibney needs.

Rather than a standard profile, Gibney reinvigorates the political-gossip drama by focusing on Spitzer’s personal and professional relationships. He highlights the corruption of the pre-crisis financial industry and the little-known world of elite-customer prostitution, asking the viewer to decide which is dirtier. There’s no easy answer for the filmmaker or his audience.

Gibney balances uncomfortable dialogues with Spitzer, who recalls his political triumphs and foibles, with straight-shot interviews with Spitzer’s political opponents, former staffers and the “brains” behind the Emperors Club VIP, 23-year-old madam Cecil Suwal. Each former Spitzer associate is given the chance to weigh in on what really brought down the Governor.

While Suwal giggles idiotically about her criminal enterprise, and Spitzer’s aides offer sympathy, the former governor’s political and personal enemies are the most engaging. Personifying Wall Street’s power, greed and distaste of government regulation, each plays scornful devil’s advocate to those who claim Spitzer was a dynamic politician who happened to have human weaknesses.

In a comically edited back-and-forth, Spitzer attempts to defend his angry outbursts against claims by Kenneth Langone, the gruff Home Depot co-founder and former Director of the New York Stock Exchange and Maurice R. “Hank” Greenberg, the soft-spoken former Chairman and CEO of AIG. They argue that Spitzer the politician broke the law, but Spitzer the man viciously threatened suspect executives, took pleasure in embarrassing white collar criminals and is undoubtedly a political and moral hypocrite. After all, as New York’s Attorney General, he prosecuted illegal prostitution rings, later to frequent one as governor.

The most fun of Spitzer’s enemies to watch are Joseph Bruno, former boxer turned New York State Senator, and Roger Stone, the infamous Republican political consultant. Both attempt to make themselves appear classier and more upstanding than the disgraced Spitzer, but the truth is in the details. Gibney divulges Bruno’s federal corruption charges in 2009 and Stone’s unscrupulous “gonzo brand of politics.” The entertaining Bruno and Stone are at least equally nefarious compared to Spitzer, or in Bruno’s case, more so since Spitzer was never charged with a crime, let alone convicted.

So, was there a Republican-Wall Street conspiracy to force Spitzer’s resignation and end his political career? More importantly, could Governor (perhaps President) Spitzer have stymied the effects of the global financial crisis if his reputation as the Democrats’ moral crusader had not been destroyed? The audience is left unsure, Gibney doesn’t know and Spitzer’s enemies repeatedly deny any criminal wrongdoing.

Luckily, Gibney does not skimp on his exploration of the ins and outs of the highly priced hooker business, which led to Spitzer’s early retirement from politics. First providing some history on the Emperors Club, he reintroduces audiences to “Kristen” (real name: Ashley Dupre), the prostitute with whom Spitzer was caught on FBI wiretap at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, D.C. After donning front pages of the New York Post and Daily News, she ended up landing a job at the former as a sex columnist. But surprisingly, Spitzer only spent that one fateful romp with Ms. Dupre.

In fact, Gibney discovered Spitzer’s favorite escort and former Emperors Club employee, who sat for an interview but declined to have her image, voice or name in the film. To account for the key character’s unwillingness to appear on camera, Gibney hired actress Wrenn Schmidt to recreate the interview. Unfortunately, the aesthetic choice runs counter to documentary tradition and may take the viewer out of the true story more than if the director had distorted the real-life escort’s face and digitally altered her voice.

In this entertaining documentary, the Oscar-winning Gibney keeps Spitzer’s friends close and his enemies closer. But ultimately the director and his audience learn more about the prostitution business than the suggested conspiracy to remove Spitzer — once the symbol of government oversight of the financial industry — from the political equation.

Nevertheless, in the perfectly timed wake of the recent midterm elections, New Yorkers and political enthusiasts should go see “Client 9.” As Gibney suggests, we should critically view Spitzer’s conservative political enemies for their supposed role in the former governor’s downfall. But we should also remember Spitzer admitted that he was his own undoing. While searching for political motives and evidence of a Wall Street conspiracy, Gibney carelessly pushes aside the central issue of Spitzer’s political demise: lust.