The 1942 Sugar Bowl and the Tragedy of Fordham Football

CHARLES L. FRANCK PHOTOGRAPHERS COLLECTION, THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION, 1979.89.7122

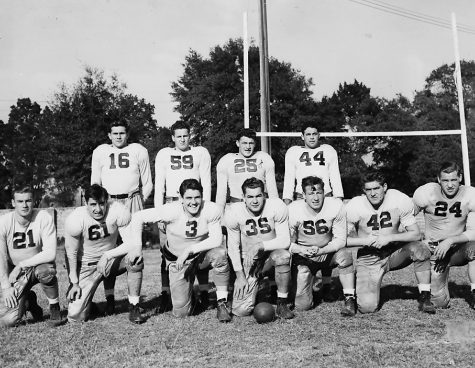

The Fordham football team won the 1942 Sugar Bowl with the lowest possible score of two points to the Missouri Tigers’ zero. Pictured here is the block that led to the Rams’ score.

August 19, 2020

2-0. Two to nothing.

The lowest possible scoring combination in the game of American football isn’t usually grounds for classification as “the outstanding triumph of Fordham athletic history,” in the words of one Fordham Ram reporter. But it was.

Three fumbles, two interceptions, one safety — and zero Fordham passing yards. Nothing about this game was ordinary.

Despite America’s declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor only three weeks prior, the game was played on schedule. It was New Year’s Day, 1942. The climax of the 1941 football season. A cold, driving rainstorm turned the field to a veritable marsh and the die-hard crowd above to a sea of umbrellas.

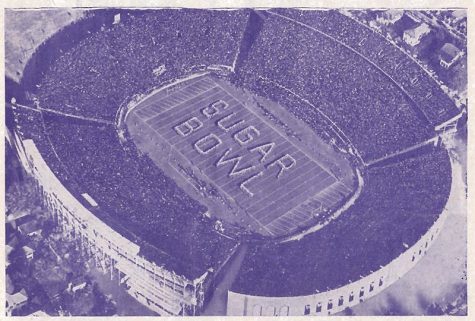

It was the eighth annual Sugar Bowl, then one of the newest premier collegiate football championships. The seventh-ranked Missouri Tigers assembled at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans to thwart the sixth-ranked Fordham Rams. This was Fordham’s second bowl game in as many years, the first a heartbreaking 13-12 loss to Texas A&M in the Cotton Bowl.

The Rams had a decade’s worth of success behind them. Having already accepted the invitation to the 1942 Sugar Bowl, Fordham was even forced to turn down a second bowl game invite that same year, this time to the Rose Bowl.

Fordham football was that good — and as it turns out, they’d never be better.

The height of Fordham’s storied era as a college football powerhouse was realized that day to the strange tune of a single safety — an uncontrollable slide in the mud through the back of the end zone for two points. Stranger still, this football pinnacle in all respects marks the great, unredeemed decline of the gridiron Rams.

Fordham’s biggest victory on its biggest stage to date happened beneath the backdrop of an even greater test of grit and faith — on a stage far larger. Two to nothing. An American beginning; a Fordham end. A triumph gone stale before the last hard-fought minute was played. Three fumbles, two interceptions, one safety — and one world at war.

On Dec. 21, 1941, 30-odd players, coaches and sportswriters departed from Penn Station, arriving in New Orleans two days later. The team practiced twice a day, every day — save for a reprieve on Christmas — leading up to the big New Year’s game. Students tuned in to the NBC Blue Network for the call, live on the radio from Louisiana. Kickoff slowly neared, and as the 66,000 spectators in attendance looked heavenward, the first drops began to fall.

“By now, everyone including Premier Tojo ought to know that during the contest, the Sugar Bowl was drenched by three tropical showers,” The Ram reported. This commentary appears on page three of the Jan. 9 issue of the newspaper. Page one is dominated by the headlines “College Considers Three-Year Plan For Degrees,” “Buy a Bomber” and “Fr. Tynan Promoted To Lieutenant-Colonel.” The staff message, page two, calls for a student-funded memorial for the alumni already killed in the Pacific theater and the countless more to come.

“Before the war is over the litany of the Fordham dead may be large,” it reads. “It is a grim thought and one that is not pleasant to express. But it is true.”

One year later, the Rams would be unranked in national polls for the first time since the practice began seven years ago. The war effort would consume the attention and enthusiasm of the United States, and the Fordham football program would be left in the dust.

Through the rain and mud, the first quarter of the 1942 Sugar Bowl began with a Missouri three-and-out and an equally unsuccessful Fordham drive. The elements severely hampered both teams’ visibility, something Fordham capitalized on in the ensuing Tigers possession. A Missouri fumble, recovered for a nine-yard loss deep in their own territory, set up their second straight punt of the game.

One year later, the Rams would be unranked in national polls for the first time since the practice began seven years ago. The war effort would consume the attention and enthusiasm of the United States, and the Fordham football program would be left in the dust. As administrators mulled expedited programs to get Fordham students off to the front, alumni were already fighting and dying overseas.

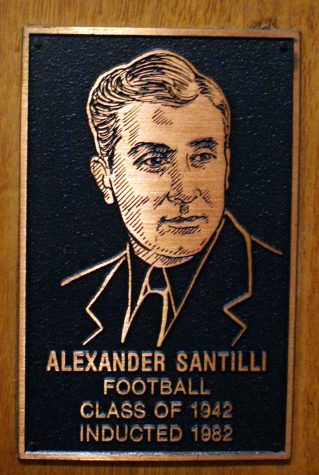

Missouri lined up for its second consecutive punt of the 1942 Sugar Bowl at its own 10-yard line. The rain was unrelenting, however, and a momentary fumble from the Tigers’ kicker gave Al Santilli, Fordham College (FC) ’42, just enough time to break through the left side of the Missouri line. Driving through the muck, Santilli struggled to find purchase in the sloughing ground, and leapt — far enough and high enough to block the punt off his chest.

The crowd must have erupted.

The ball caromed into the end zone, and the 22 men on the field raced towards it. Fordham’s own and Missouri’s finest fell over each other, single-mindedly pursuing the live football, wobbling erratically towards the sideline.

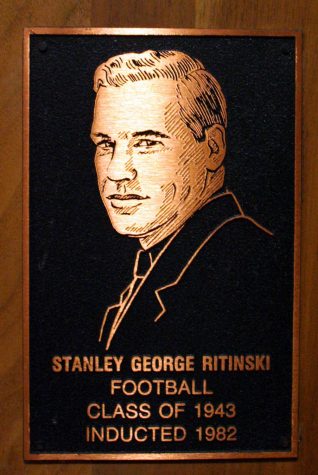

The Rams’ defensive end, Stanley Ritinski, FC ’43, led the charge. He knew the stakes: Recovering the blocked kick meant an early Fordham touchdown — seven points and first blood in a game that the weather would not permit to be very high-scoring at all.

Falling to the ground, Ritinski skidded through the end zone after the ball, juggling it in his hands before finally controlling it as he crossed the back of the end zone, coming to rest out of bounds.

One wonders if the young men assembled that day knew the significance of the moment they were living. Did they know what the years would bring? Did a lull in the action bring enlistment worries and Navy transfer papers back to the forefront of consciousness? Did they know that, in that very Louisiana quagmire, Fordham football would hold tight — if only for a moment — to its brightest hour? Or was the 1942 Sugar Bowl already lost to the footnotes of time, sucked into the black hole of war looming on the horizon even as they lived it?

The Rams’ celebration of Ritinski’s touchdown was, unfortunately, short-lived. Referee William Halloran tempered the heart-pumping early-game Fordham score with his final ruling: Ritinski did not have possession of the ball until after he slid through the back of the end zone.

Not a touchdown, but a safety. Fordham 2, Missouri 0.

It would remain this way for the next 54 mud-soaked minutes of the game. The highly anticipated explosion of offense from the two talented teams fizzled in the Louisiana deluge. Three fumbles, two interceptions, one safety — and zero Fordham passing yards.

Rams win. 2-0.

It doesn’t matter how good a college football program is. It doesn’t matter how storied its greatness may be. Fordham — and its students — knew where their priorities lay. By year’s end, Fordham football had lost many of its own stars to military colleges, where the ex-Rams continued their passion for football before shipping out with the Army or the Navy.

1942 began with a historic win for the program, but it ended with a win against many of their own. In the last game of the Rams’ season, Jimmy Crowley — now Lt. Commander Jimmy Crowley — led the North Carolina Pre-Flight School Cloudbusters against the Fordham team he had coached for eight years. Eleven former Rams and three former coaches numbered among the enlisted lineup for that game alone. Fordham won the game, 6-0. If, in the grand scheme of things, that matters at all.

The Rams ended the 1942 football season with five wins, three losses and one tie. They were outscored 155 to 103. The glory Fordham captured less than a year before had faded. Those young men at the top of college football — posed to solidify a new dynasty and cement the Rams at the heart of the sport — gave it all up. However great the promise of Fordham football was, their allegiance was to something greater.

The “Stamp-ede The Axis” committee set up a table in the cafeteria in October 1942, selling war stamps. Graduate Athletic Manager John “Jack” Coffey optimistically released the Rams’ 1943 schedule the next month, the place of football on Fordham’s campus in the coming years still unknown. The writing, however, was on the wall.

On New Year’s Day of 1942, the young men that lined up in the driving rain at Tulane Stadium might have already known that the game they were playing was moot. A last gasp, not a first step. A flash of glory — of youth, of pride — eclipsed as inevitably as Santilli blocked the kick.

The end of the Cloudbusters game and 1942 season carried with it the decision to suspend the Fordham football program for the duration of the war. When peacetime returned, the university fielded a de-emphasized and largely unsuccessful team for the next decade — before Fordham football was dropped altogether in 1955.

In 1970, Fordham football returned to the NCAA after its revival as a club sport six years prior. They returned to the Division I stage in 1989, where they compete to this day. Though the program has achieved moderate success in its modern era, Fordham football has never won another major national championship.

For the record, Missouri didn’t fall to Fordham 2-0 in the 1942 Sugar Bowl for lack of trying. Three times, the Tigers broke off big gains and drove within scoring distance, but three times the Rams denied them. The rain ebbed for a few moments in the final quarter, and a Missouri field goal attempt went up — straight and true — but fell yards short of the crossbar. The lowest possible combined point total in American football, despite all efforts from both sides to the contrary, stood. It must have been meant to be.

The tragedy of Fordham football is bittersweet. No lack of funding, failed recruitment program or internal corruption allowed the dynasty to fade to black. They sacrificed it willingly. As “BUY WAR BONDS” and “RADIO SCHOOL – GET BETTER NAVY JOBS” filled The Ram’s weekly issues, players and coaches alike relinquished bright futures at Fordham to serve the United States in the Second World War. While football remained in their lives, Fordham maroon — and all the prestige it implied — simply wasn’t theirs to claim anymore.

Fordham men saw something far greater worth fighting for in the war effort. Some, like First Lieutenant Santilli, paid the ultimate price.

“Lt. Santilli of the Marines, former Fordham football tackle, was killed by a Japanese sniper while leading a charge in the bloody fighting at Saipan on July 8,” reported the Dunkirk Evening Observer. “He wasn’t scheduled for action that day. He had been ‘benched’ for shell shock.”

“But big Alex, star of Fordham’s 1942 Sugar Bowl victory over Missouri, couldn’t sit on the bench while his mates were battling down the Saipan field in rough going. The spirit impelled him to join the fray, and the rugged body he had developed on the gridiron permitted him to carry on heroically despite his shell-shock.”

Of the 230 Fordham alumni killed in World War II, Santilli was one. Players, coaches and fans undoubtedly number among him. Such loss — one year removed from such triumph, such hope — is nothing short of a tragedy.

On New Year’s Day of 1942, the young men that lined up in the driving rain at Tulane Stadium might have already known that the game they were playing was moot. A last gasp, not a first step. A flash of glory — of youth, of pride — eclipsed as inevitably as Santilli blocked the kick. As inevitably as Ritinski slid through the back of the end zone. As inevitably as Missouri’s kick fell short. As inevitable as the final score.

Two-nothing. Three fumbles, two interceptions, one safety — and a triumph the likes of which Fordham football has not seen since.

Chris Doyle • Aug 9, 2025 at 7:52 pm

There should be a memorial to the Fordham alum lost in World War II.