Warhol’s “Last Decade” Occasionally Revelatory

Brooklyn’s Exhibition Displays the Artist’s Final Years of Experimentation

July 23, 2011

Published: August 25, 2010

Andy Warhol has a place in our collective cultural knowledge like few other artists. If Leonardo da Vinci is forever associated with “Mona Lisa” and Van Gogh with “The Starry Night,” then Warhol has his “Campbell’s Soup Can;” “A Shot of Marilyn Monroe;” the cover of one of the most renowned records of all time, the Velvet Underground’s “VU and Nico;” and countless other images. You’re not likely to see Monet or Matisse’s work on many handbags draped over the shoulders of New York twenty-somethings, but you will see Warhol’s. Famous or infamous, everybody knows Warhol. So it’s refreshing to get the rare chance to reassess ideas that seem concrete, an opportunity that Brooklyn Museum’s “Andy Warhol: The Last Decade,” attempts to afford us.

Warhol’s never-before-exhibited prolific final era begins with the artist, spooked from the 1968 attempt on his life, growing tired of the typical cut and paste processes of his Factory. A quote featured early in the exhibition expresses his feelings at the time: “How can you say that one style is better than another? You ought to be able to be an Abstract Expressionist next week, or a Pop artist, or a Realist, without feeling you’ve given up something.” Distancing himself from Pop Art and the obviously identical machine-like prints from which he had found fame, Warhol began creating abstract images while retaining his impersonal style. As seen in “Yarn,” a white canvas with a seemingly endless, bundled, overlapping, color-shifting line, similar to Jackson Pollock’s art, Warhol took a stab at abstract expressionism with a twist. The deceiving work appears to be hand-painted, though upon closer inspection, it is screen-printed in typical Warhol fashion, raising questions about the nature and importance of the artist’s hand in his work.

Following his abstract work is a collection of paintings he and the great neo-expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat worked on together. In a cat-and-mouse game, Warhol would screen his images onto a canvas and Basquiat would then add his graffiti art over it, melding their most famous styles together. These works are symbolic of much of Warhol’s life in the 1980s, as he became friends with many in the young New York City art scene. However, while the collaborative paintings certainly differ from most of Warhol’s collection, Basquiat’s style shines through this work the brightest, perhaps because his turn at painting came second or simply because his personality is louder in them. For instance, in 1985’s “Sin More (Pecca di Piu),” Warhol had originally screened the phrase “Repent and Sin No More,” a reoccurring slogan in his work, but Basquiat humorously refutes it, leaving only the words “Sin More” unobstructed. It’s as if the artists’ personal ideologies clash alongside their creative ideologies. Here, Basquiat wins the fight and their collaborations become only an amusing diversion from insight into Warhol’s inspiration as he grew older.

Oddly, the exhibition space abruptly ends there, before visitors must find the elevator and venture up to the fifth floor to find the rest of “The Last Decade.” The strange layout certainly doesn’t help the exhibition, though I sympathize with curator Joseph D. Kenner II, who sought to create an important show with limited space. Luckily, Warhol’s remaining work on exhibition is more intriguing and strangely more personal than that which preceded it. 1984’s “Rorschach,” a huge image of the psychoanalytical test for which it is named, made by painting acrylic blots on one side of a canvas before folding it for a symmetrical whole, is experimental like most of Warhol’s work during this period, and was, as usual for Warhol, created by an entire team of people. But it’s also unique because, well, it’s unique. The strange design is imperfect and one-of-a-kind and, like the actual Rorschach tests, blatantly asks for a personal interpretation of any image the mind assigns to it. While still having the Warhol touch, or lack thereof, it is seeking a wildly different result from, say, a print of Dennis Hopper or Mick Jagger.

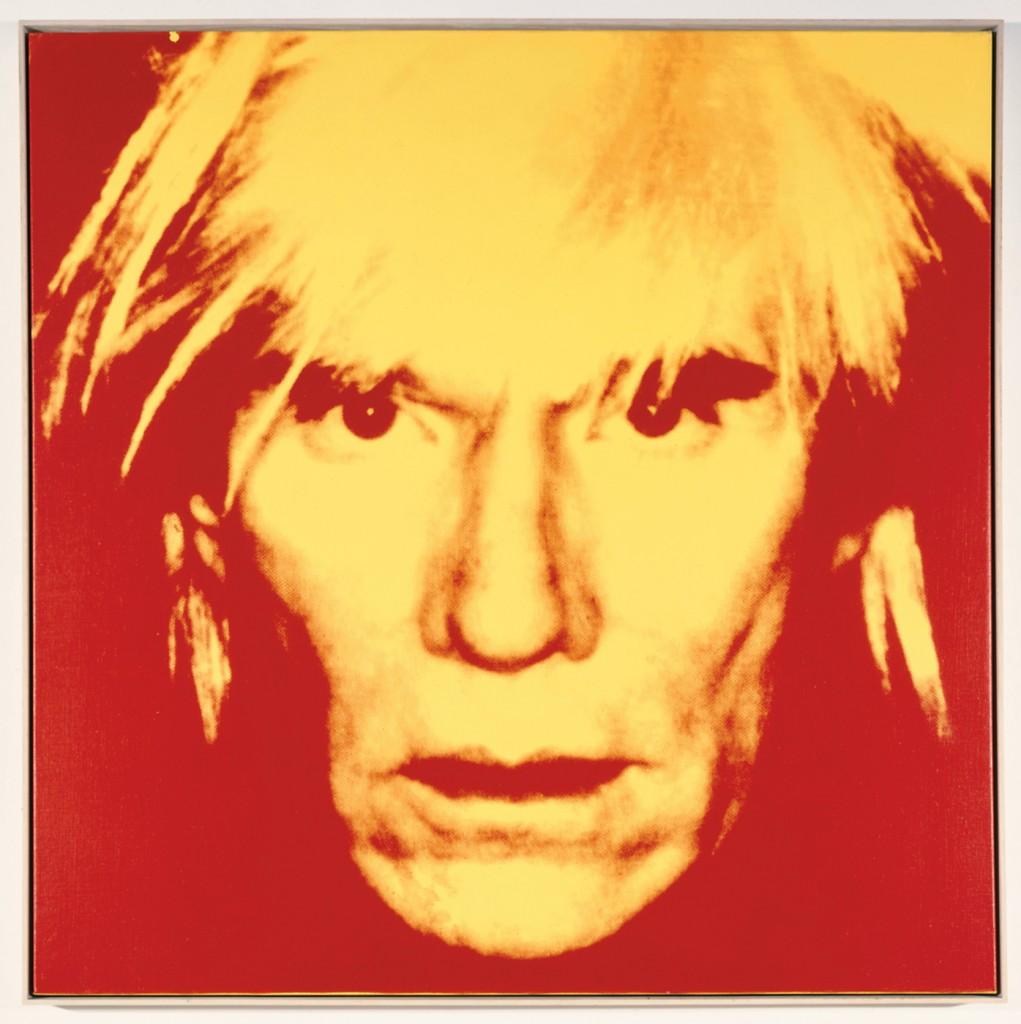

Even more personal and divergent from Warhol’s past are his final religious works, “The Last Supper” series, on which he worked feverishly for more than a year. Nearing the end of his life, Warhol, a secretive yet incredibly devout Catholic, filled his work with Christian iconography (if you go, listen via cell phone to Warhol’s studio executive manager Vincent Fremont and Brooklyn Museum curator Joseph Ketner swap anecdotes about dropping Warhol off each day at church in Manhattan). His version of the Last Supper, created to hang in Milan just across the street from DaVinci’s original, is an exact copy of the source, though painted in grainy yellow and black colors evoking his preferred screen printing process. Nevertheless, Warhol claims to have painted the giant canvas alone, by hand. The painting is gorgeous, and “The Last Decade” culminates with the full scope of Warhol’s talent and identity at its most vulnerable, stripped of extraneous input and calculated pretense, respectively.

Nevertheless, the exhibition of Warhol’s final paintings largely proves to be both captivating and prophetic yet frustratingly guarded, just like the artist on display. For every telling moment of spiritual or personal insight into Warhol’s creative process, there is another photo to remind you of him palling around with Pee-Wee Herman and Sylvester Stallone, another episode of an MTV series he helmed. Warhol was a complex human being but “The Last Decade” does little to further him from the commercial and star-filled world he adored, and the image of him ingrained in the collective subconscious. The exhibition does show a fearless artist; however, using foreign materials and experimenting with new methods of production even in the last stage of his life. And upon reaching the end of the “The Last Decade,” the point of his literal and creative death, perhaps it is a fitting memorial for Warhol that visitors realize the truly inseparable nature of his life and his celebrity.