No Mere “Wrinkle in Time;” Madeleine L’Engle’s Death at 89

May 27, 2011

Published: September 27, 2007

FCLC—Third grade: my ambitious, grubby hands held an intriguing novel wrapped in crinkly library binding: “A Wrinkle in Time.” With anticipation, I cracked open the first few pages and greedily devoured what followed. I was hooked.

When I returned to the novel (and its three sequels) years later, I found myself overcome with that same fascination, that same curiosity, that same single-minded determination to claw my way through those pages without pause.

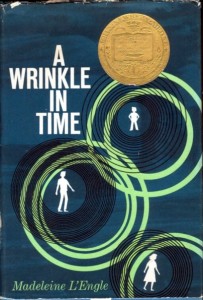

Madeleine L’Engle, children’s book author and literary diva of quantum physics, passed away on Sept. 6 due to natural causes in a nursing home at the age of 89. A New Yorker at heart, she was born on Nov. 29, 1918 and raised here, dividing her time between New York City and Crosswicks, Conn. throughout her life. It was on a camping trip when the plotline for “A Wrinkle in Time” came to her. Although the novel was completely finished in 1960, finding a publisher proved to be difficult, and “Wrinkle” did not get published until 1962.

“A Wrinkle in Time” was L’Engle’s first published work and the first in her most famous and esteemed Time Quartet. “Wrinkle’s” main character, Meg Murry, is visited one “dark and stormy night” by the mysterious Mrs. Whatsit. Meg, joined by Calvin O’Keefe, a school friend, and Charles Wallace, her uber-genius of a five-year-old brother, travels to new dimensions with the help of the aforementioned Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which. Tesseracts, cosmic folds in time and space, are the primary means of light-speed travel in “Time,” and the three soon arrive in Camazotz to battle “IT,” one of the vilest and disturbing villains to ever grace children’s literature.

“A Wind in the Door” (1973), “A Swiftly Tilting Planet” (1978) and “Many Waters” (1986) were the three sequels to “A Wrinkle in Time.” These, and the O’Keefe quartet that followed, chronicled two generations of the same O’Keefe/Murry family tree.

These two quartets (combined titled the “Kairos” series), and her novels regarding the Austin family (the “Chronos” series) made modern science concepts accessible to any voracious reader. DNA, time travel, alternative dimensions, tesseracts, organ regrowth—no subject was too audacious, and L’Engle summarized daunting concepts into easy-to-digest chunks of literary bliss. These hard science ideas had only previously appeared in textbooks, scientific journals and adult novels too dense for young adults and children to comprehend. By making science easy and accessible to the masses, L’Engle pioneered a trend of making difficult theories digestible through fiction. Rick Manista, FCLC ’09 agreed with these sentiments. “What I love about her was that she incorporated science into her stories but made it fantasy instead,” explained Manista. “I read her throughout elementary school.”

L’Engle spent most of her life teaching and writing, offering her services as a volunteer librarian and spending time with Hugh Franklin, her husband. After complications due to a cerebral hemorrhage, keeping up with her busy schedule became too difficult for the ailing L’Engle, who spent her final days in a nursing facility until her death, a mere two months before her 90th birthday.

I, like most of FCLC’s community, grew up loving and treasuring L’Engle’s fiction, for its timelessness and mass appeal. “‘A Wrinkle in Time’ was my favorite book for a long time,” Sydney Painter, FCLC ’09, said of L’Engle’s most seminal work. “I read it about six times.”

Professor Margaret Lamb, head of the creative writing department at Lincoln Center, met L’Engle personally several times, “She used to teach a class at the Cathedral of St. John’s the Divine. When I met her, she was already a grandmother, and dressed in a medieval way.” Lamb continued, “She was a wonderful person when talking about her work, and lively and interesting as a writer.”