Uncovering Cuban Baseball’s Bronx Origins

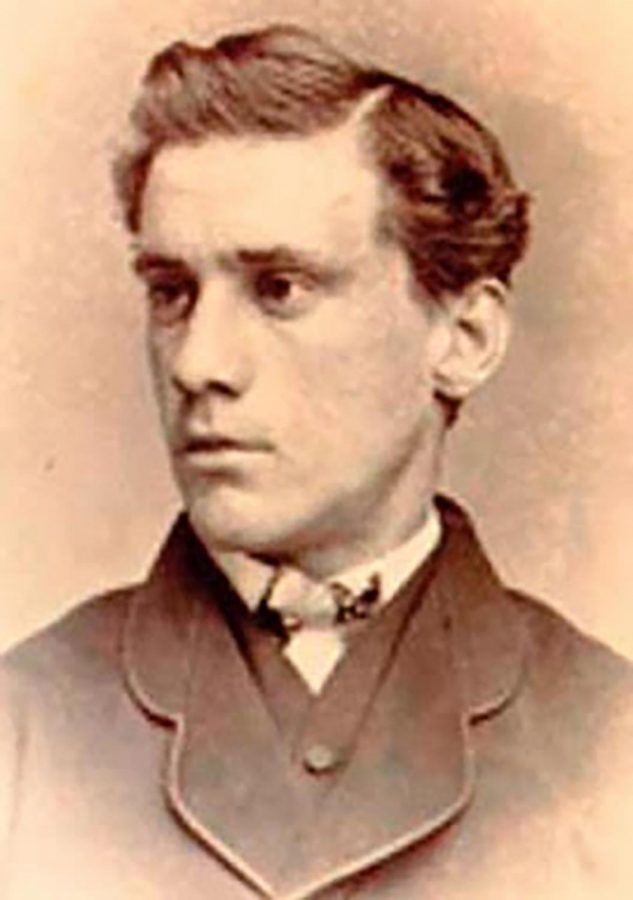

COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN BASEBALL RESEARCH

Estevan Bellán attended St. John’s College, which would later be renamed Fordham University, between 1863 and 1868.

April 28, 2020

If Cuba were an American state, it would be one of the highest producers of professional baseball players in the country. In 2018, 26 Major League Baseball players came from Cuba, a greater number than 40 states and Washington, D.C., despite strict immigration laws making their path much more difficult. To understand how baseball became more important in a foreign country than in most of the United States, one has to know the story of 1800s Fordham baseball player Steve Bellán.

The prominence of baseball in Cuba and other Latin American countries began in the 1860s. At that time, American sailors introduced the game to Cuban children during their stay on the island. At the same time, Cuban students began bringing it back after receiving their education stateside.

One of these men was Estevan Enrique Bellán, known colloquially as “Steve,” the son of a wealthy Cuban family from Havana. At the time, it was common practice for wealthy Catholic children in Cuba to be sent to the United States for a formal education. When Bellán was 13, he traveled with his mother, brother Domingo and sister Rosa to New York.

That fall in 1863, he enrolled at St. John’s College, a relatively new school in the Bronx built on Rose Hill Manor. It would be another 44 years before the school was renamed Fordham University, but Bellán’s introduction to the rest of his life began in the rudimentary fields of the Fordham area.

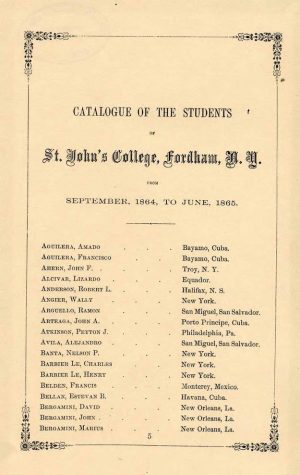

An administrative building from when Bellán was enrolled at Fordham in the 1860s, then called St. John’s College.

There is some uncertainty as to when Bellán first learned about baseball, as its introduction in Cuba did not begin in earnest until a few years after his departure. Regardless, Bellán became increasingly familiar with the sport during his time in America, and at 16, he joined the varsity team, then known as the St. John’s College Rose Hills, or the Fordham Rose Hill Baseball Club.

At this time, baseball was very different. There were still different variations of the sport by region, with the New York variety eventually popularizing the nine-man lineup. Balls were pitched underhand and gloves were not used. Regardless, Bellán played intercollegiate baseball at a time when it was very new, batting leadoff and catching for St. John’s against teams around the country.

This an excerpt from a student catalogue and registration ledger from the 1860s at St. John’s College, where Bellán joined the varsity baseball team.

While often cited as an alumnus of St. John’s, there is no record that Bellán ever graduated. At some point in 1868, he left school to pursue a career in professional baseball. He joined the Union of Morrisania baseball club, which took him around the country on various road trips. At some point, his entire family moved upstate in order to accommodate his shift to the Troy Haymakers.

At some point during his run in professional baseball, Bellán switched positions from catcher to third baseman. In a gloveless era, the Baseball Hall of Fame reports that he was an exceptional fielder, earning the nickname “The Cuban Sylph” for his grace at third. Despite an “erratic” arm and “average hitting skills,” the Hall of Fame archivists also found an article quaintly describing him as “one of the pluckiest of base players.”

After a short stint in 1873 with the New York Mutuals, Bellán and his family returned to Cuba. He arrived home to a country that had taken to baseball almost as fervently as he had in New York. Baseball had grown considerably in popularity since he had left in 1863, and the Cuban Sylph found himself a pioneer in a booming industry.

Baseball was so popular in Cuba that it became a symbol of rebellion. In 1869, baseball was banned by the imperial Spanish government in an effort to affirm bullfighting as the national sport. This led to unrest in Cuba and popularized baseball even further.

After playing baseball in Cuba for the better part of the decade, Bellán was integral to its official formation. In 1878, he was the player-manager in the first organized baseball game in Cuban baseball history in a game between his team Club Habana and Club Matanzas. He went on to lead that team to three Cuban League championships, with the third coming in the 1882-83 season. He, among others, is commonly referred to as the Father of Cuban Baseball, and the Club Habana baseball team he helped found lived on until 1961, when the new government leader Fidel Castro banned professional baseball again.

In a speech commemorating 150 years of baseball at Fordham University, President Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., said that through Bellán, “Fordham taught the Caribbean how to play baseball through the connection from Jesuit high schools in Cuba to St. John’s College.”

While Bellán didn’t introduce baseball to Cuba, he took a rising sport in his home country and used his American experience to shape it into an official organized sport. Even after another ban on professional baseball in 1961 following Castro’s takeover, baseball survived and lives on as the national sport of Cuba.

In recent years, before tensions were eased between the countries, many Cuban baseball players risked their lives to reach the United States and the MLB. Yasiel Puig, Yoenis Cespedes and Aroldis Chapman all stand as modern testaments to Bellán’s original dream: to play professional baseball at any cost. They all defected under threatening circumstances, far more threatening than Bellán faced, but the culture he helped to establish a century and a half earlier ingrained in all of them a dream to pursue a sport they had seen as a way out since childhood. Bellán may have been the first Cuban professional baseball player, but his contributions over three decades in the sport ensured that many more would follow.