The Implications of NY State’s Plastic Bag Ban

New York’s various iconic “Thank You” bags may become relics of New York City’s past with NY state’s recent legislation.

March 18, 2020

Before plastic bags, there were paper bags, and before that, reusable sacks made of natural fabrics including canvas, burlap or jute. With the gradual ban of single-use plastic bags and the reintroduction of paper and reusable bags, New York, along with many other states and countries around the world, is reverting back to archetypal techniques for the transportation of goods.

On Sunday, March 1, New York state’s long-anticipated bag waste reduction law was enacted. The legislation bans the distribution of all single-use plastic bags. It applies to the majority of New York businesses with some exceptions, including plastic bag usage for prescription drugs, produce in bulk, dry cleaning and uncooked meat. All businesses are required to charge a 5-cent tax on paper carryout bags which will replace plastic. The Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) encourages people to avoid the tax by bringing their own reusable bags.

The new legislation is the result of New York’s multi-year report, “An Analysis of the Impact of Single Use Plastic Bags.” The report was initiated by Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Fordham College at Rose Hill ’79, who convened the task force that executed the research. It reported on the environmental impacts of the state’s widespread single-use plastic bag usage and proposed possible legislation to address the issue.

Enforcement of the new law was originally set to begin April 1. However, an order signed on Monday in the New York State Supreme Court postponed enforcement until May 15. Once enforcement begins, businesses which violate the ban will first receive a warning, then a $250 fine and finally a $500 fine for an additional violation within the same year. The gradual transition provides time for businesses to distribute the sum of their remaining plastic bags and for consumers to adjust to the changes.

Monday’s legislative change is not confirmed as a direct result of the global pandemic. In the past week however, some questioned whether the ban should still be enforced come April 1 amid the escalating outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19). In a recent New York Post article, researchers have alerted public officials in the past that reusable bags can be supreme conduits for the spread of bacteria and pathogens, especially if they’re not washed regularly.

Often taken for granted, bags become even more essential amid a global pandemic. With New York ordering a take-out and delivery only rule for restaurants and panic shoppers clearing out grocery store shelves, New Yorkers will depend on bags, whether plastic, paper or canvas.

Last Tuesday, Republican Leader of the New York State Senate John Flanagan said, “Senate Democrats’ desperate need to be green is unclean during the coronavirus outbreak.”

Mayor of Waterville, New York, Nick Isgro shared a similar concern. On Sunday in a Facebook post, Isgro said that he planned to ask the city council to temporarily suspend the ordinance and to encourage retailers to ban customer usage of personal bags at the city’s first COVID-19 task force meeting on Monday. He expressed concern that reusable tote bags — though sustainable — could host COVID-19 and spread the virus throughout stores and people’s homes.

The New York State Supreme Court’s decision to temporarily suspend the ban’s enforcement has not been officially linked to the concerns voiced by Flanagan or Isgro. However, the change came simultaneously among sweeping executive orders made by the state to curb the spread of the virus.

While current circumstances add new layers to the long existing debates between paper, plastic and reusable bags, many people agree that New York state’s recent legislation was a positive action.

Fordham University Associate Professor of Theology and Science and Ethics Christiana Zenner said, “Let’s appreciate that this is a step forward.”

Zenner is the author of “Just Water,” a book addressing the overlapping issues of water quality and plastic waste. The book investigates the various solutions Catholic social teachings have proposed to these problems in recent decades.

Abbie Davidson, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’20 and president of Lincoln Center’s Environmental Club, shared a similar sentiment. “The ban shows that people are starting to understand where some of the problems lie and how they as a consumer can make active decisions on behalf of protecting the planet,” she said.

Second-generation owner of Mike’s Deli on Arthur Avenue in the Bronx, David Greco remembers a time before plastic bags, when customers used these company-branded paper bags in the 1970s.

Plastic bags became popularized in the 1970s, shortly after Swedish engineer Sten Gustaf Thulin had the idea to add handles to the early handle-less plastic bag prototypes. Patented as the “t-shirt bag,” it was quickly adopted as the most convenient contraption for transporting all goods. It was produced for a cheap price tag, too.

Plastic bags are made from the waste products of oil refining and require large amounts of energy for production. In a landfill, it takes up to 500 years or more for a plastic bag to degrade. Plastics can’t break down entirely, and instead become microplastics which absorb toxins and pollute the environment. Waterways are especially vulnerable to this pollution.

However, the sustainability of paper bag production is called into question as well. “There are, of course, concerns of the impacts on forests of the increased demand on paper bags,” Zenner said. “There are unintended consequences (even if foreseen) of all forms of action.”

According to a 2011 report written by the Northern Ireland Assembly, paper bags require more than four times as much energy than plastic bags for production. This is because forests need to be cut down for necessary raw materials. Additionally, paper bag production was reported to produce 70% more air pollutants than plastic bag production.

In terms of biodegradability, paper bags take only two to six weeks to biodegrade completely inside a landfill as opposed to 500 years or more for plastic bags.

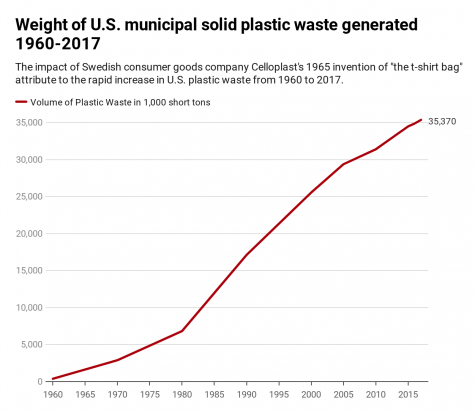

On the DEC’s website it states that New Yorkers currently use an estimated sum total of 23 billion plastic bags per year, making NYC a major contributor to plastic waste generation in the U.S. (Data Courtesy of United States Environmental Protection Agency.)

With the threat of climate change growing, Zenner considered the determining factors for effective green policymaking. She said, “The question becomes, how do we choose the best courses individually with awareness of potential downstream actions?

“How nimble can our individual, community and governments responses be in response to new data, making adjustments to both practices and policy?” she added.

Zenner’s contemplations become even more complex in the midst of New York’s current circumstances. It is unclear whether postponing the ban’s enforcement came in an effort to increase safety measures. As the number of positive COVID-19 cases in the state grows every day, orders from the state government rapidly evolve.

The timing of the initial legislation may not have been ideal, though enforcement beginning May 15 will push New Yorkers to adopt more sustainable habits, and consequently reduce plastic waste.

Davidson, who viewed the ban as a victory for environmentalists, expressed it might allude to something bigger. “I hope this is the beginning of widespread policy change. I think by the time our generation’s in office, we’ll see a ridiculous bout of environmental legislation.” she said.