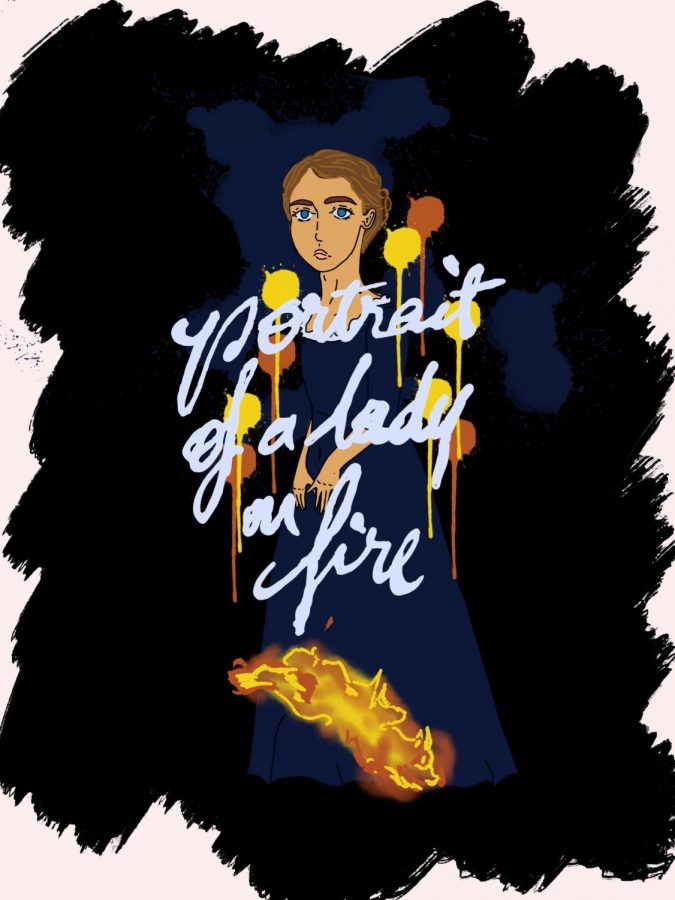

‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ Tells of a Timeless Romance

March 10, 2020

A specter is haunting Celine Sciamma’s latest film — the specter of a love unfulfilled and repressed. Since her debut in 2007 with “Water Lilies,” Sciamma has been committed to exploring aspects of the gender and sexual orientation of young women through film, and “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” is no exception to this trend.

The film is about a young painter, Marianne (Noémie Merlant), who is commissioned to make a portrait of a young woman, Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), to be sent to her betrothed. The two women are left alone in a manor with a young maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), and love and friendship blossom between the three of them.

Unlike her previous films, this is not a coming-of-age story. This is emphasized by the English title’s use of the word “lady,” in contrast with the French title, which instead refers to Héloïse as a “jeune fille,” or “young woman.” While each of the lead actresses was about 30 years old during the shooting, there’s a sense that their characters are supposed to seem emotionally immature as a result of not having been able to express their romantic feelings for other women before.

The film’s aesthetic is, to put it succinctly, fire. The sets of the French seaside manor are fantastic, but the most memorable visual aspects are the movie’s costumes and cinematography. The dresses worn by the two leads are both simple and luxurious — often only of a single color, such as the magnificent green gown that Héloïse wears while sitting for the portrait, but with such texture that you can imagine just how they feel by watching them on screen. And the cinematography truly brings to mind the phrase “every frame a Rembrandt” — almost every shot looks like it’s dying to be printed out and made into a poster or desktop wallpaper.

The movie’s core draw is its incredibly felt romance, yet a great deal of the film’s strength lies in its knowledge of its apoliticism. Which isn’t to say that the main conflict in the film, that queer lovers have historically been forced apart from each other by society and the individuals within it, is devoid of politics.

This is a message that’s been repeated to the point of contrition, with a recent example being “Call Me By Your Name,” but it is still a reality for many people. In this sense, “Portrait” ends up being far more political than the actual French Oscar nominee, Ladj Ly’s “Les Misérables,” which pretends to make a political statement but ends on a dangerously apolitical note.

In other words, choosing to be apolitical is a political stance. By choosing not to be didactic about the issues discussed in the film, Sciamma causes the audience to feel the message that much stronger. Compare this to Ly’s utilization of the awful “everyone’s bad, even when they try to do good” that’s featured in every last movie about police officers and transplants it to the banlieues, which are roughly the French equivalent of what we call the “projects” in the United States.

It’s a shame that a greatly affecting work of art went unrecognized, while a failed attempt at moralizing ended up becoming the French submission. At least I can rest easy knowing that either film would have been demolished by “Parasite” in the new Best International Feature Film category anyway.