Period. End of Stigma?

GRAPHIC ILLUSTRATION BY ESME BLEECKER-ADAMS

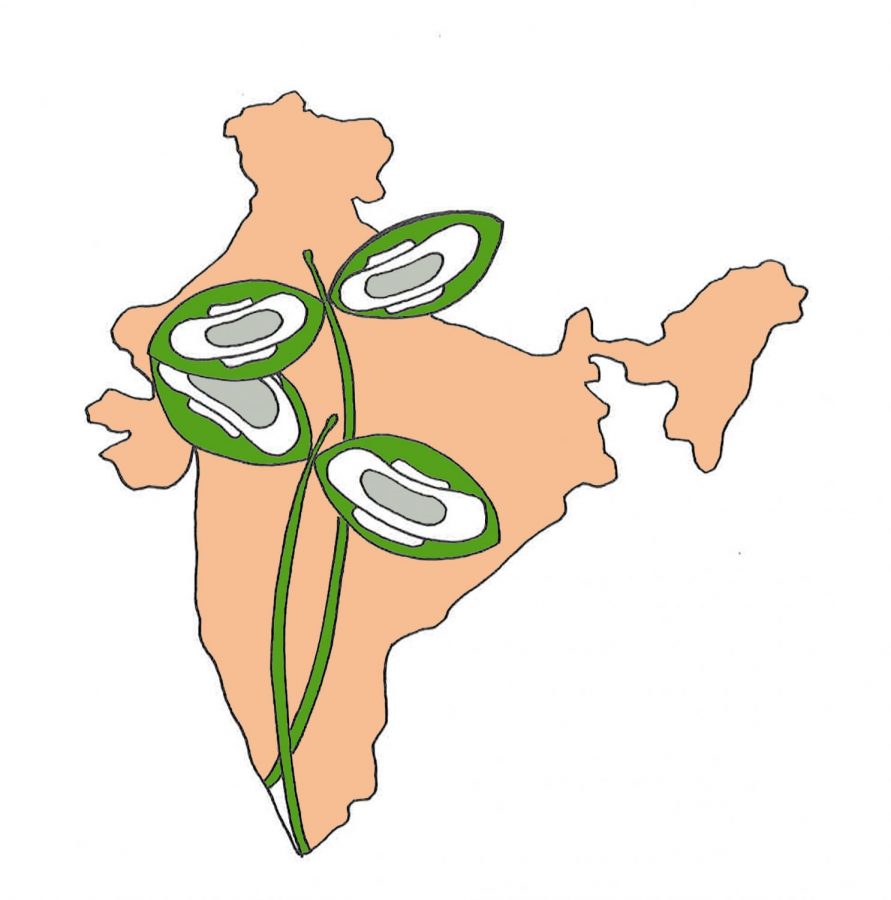

Rayka Zehtabchi tackles the movement for menstruation awareness in India in her Oscar-winning documentary.

March 31, 2019

When the filmmakers behind the documentary “Period. End of Sentence.” won an Academy Award for Best Documentary (Short Subject), director Rayka Zehtabchi said, “I’m not crying because I’m on my period or anything… I can’t believe a film about menstruation just won an Oscar.” Zehtabchi’s remarks call to attention the stigma surrounding menstruation that exists in the United States today. However, Zehtabchi and her crew did not try to tackle the stigma in the United States in their documentary. Instead, they covered the stigma and ignorance surrounding menstruation in India.

“Period. End of Sentence.” follows Sneha, an Indian woman who dreams of becoming a police officer for the Delhi police force, but who first wants to bring accessible and affordable sanitary napkins, or pads, to the women of India. Sneha’s goal is realized through the philanthropic efforts of high school girls in California’s Oakwood School and because of an invention by a local inventor, Arunachalam Muruganantham — a pad-making machine. Sneha, along with other women from surrounding villages, begin making pads. They make pads from 9 to 5, or whenever the electricity is working. After making the pads, they distribute them and give information sessions about periods and pads to those who will listen. Their pads are sold under the brand name Fly because the women behind the brand “want the women [they sell to] to rise and fly.” This sentiment is rather telling of the situation many women are in because of the stigma surrounding menstruation in India. Women do not have access to proper pads, so they bleed through their clothing more easily and are made more uncomfortable by the protection they do wear. Due to these factors, many women drop out of school and become less active members of society.

“Period. End of Sentence.” is a simple but beautiful documentary. It effectively explains the stigma, the reasons it is so harmful and the ways in which people, mainly women, are trying to combat it. The documentary also utilizes a basic tool of narrative filmmaking: “show, don’t tell.” Zehtabchi does not need to explicitly say that Indian women are embarrassed or restricted because of the period taboo and limited pad accessibility. he shows us through the shy and confused faces they display around others or in their classes when asked about menstruation. “Period. End of Sentence.” is brightly colored, with clear cinematography that highlights the happiness, brilliance and determination that fills the faces of the women behind Fly. Also, while scores always seem to be underappreciated in films, the swell of the music by Osei Essed, Giosue Greco and Dan Romer comes at every emotional moment — like an effective score should do — and you can’t help but remember it.

“Period. End of Sentence.” hits every mark, and it does it in just 26 minutes. Especially when watching this film as a woman, it makes me proud (and a bit teary-eyed) to know that women are supporting women, like Zehtabchi supporting other women with her documentary, Sneha supporting other women with Fly and the girls of Oakwood School supporting other women through The Pad Project. “Period. End of Sentence.” is one of the best feminist projects of the year because of its goal to educate, not embarrass, men or women for lack of information, and because of its empowering remarks and messages presented to the women in the film and in the audience.

Kathleen Bonann Marshall • Apr 3, 2019 at 1:05 am

We should all be proud of the Pad Project at Oakwood School in LA, and the extraordinary understanding and commitment made by teacher, Melissa Berton, and her students—including daughter and executive producer of Period. End of Sentence, Helen Yenser.

At a time when we most need heroes, these amazing women are mine!!