Doctors Have a Duty to Care, Not Discriminate

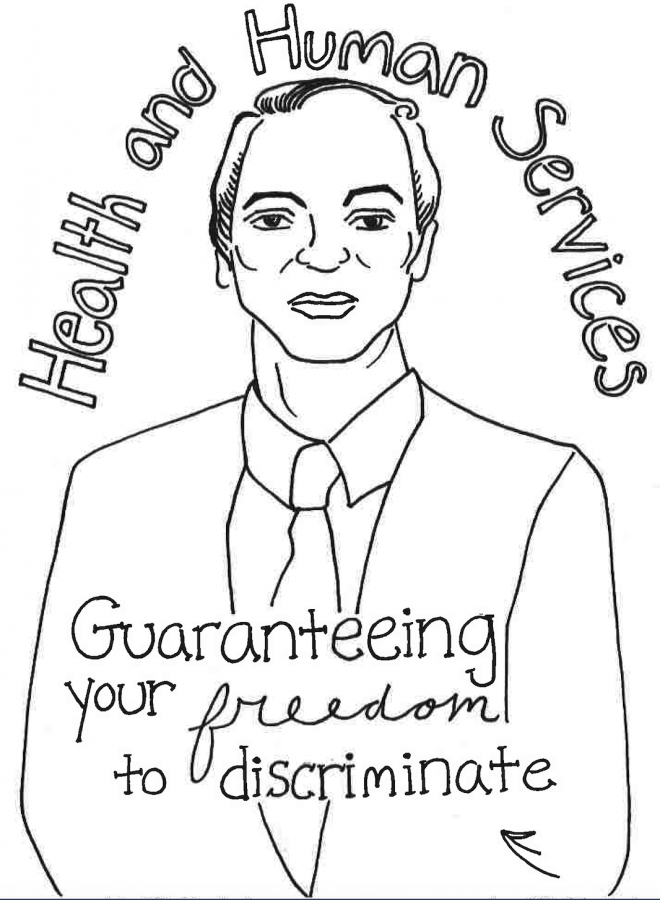

GRAPHIC ILLUSTRATION BY ESME BLEECKER-ADAMS

Roger Severino, director of OCR, seeks to expand the ability of doctors to discriminate against patients.

March 28, 2019

When I was growing up, I hated going to the doctor’s office because of the possibility of needles and scary tools. But not once did I think my physician would discriminate against me because of my identity.

It never crossed my mind that there were millions of people in the country who refrain from paying their physician a visit for this very reason. So many people lack the agency to go to their doctor and rightfully ask questions about their bodies and health. They harbor fears and concerns that their physician will pass judgment on them and treat them unfairly because of who they are.

These fears are not unfounded. Even though doctors are supposed to be completely devoid of judgment when treating their patients, federal policies allow doctors to discriminate against their patients. Across the country, doctors are allowed conscience protections which allow them to refuse to treat patients based on their “religious” beliefs.

These protections are derived from laws passed under the Bush administration such as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 as well as the Church, Coats-Snowe and Weldon Amendments, which all shield healthcare workers from carrying out different procedures and treatments that conflict with their religious views.

Roger Severino, director of the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the Health and Human Services (HHS), aims to strengthen these conscience protections laws for doctors. After President Trump signed the executive order “Promoting Free Speech and Religious Liberty” in 2017, OCR founded the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division in order to enforce pre-existing conscience protections laws in 2018. The new division will make it mandatory for all healthcare centers to post these laws in their facilities.

Under these conscience protections, doctors are able to refuse to treat patients if they have a “moral obligation” against the treatment. Although these laws existed under the Obama administration, the scarcity of cases regarding any alleged religious discrimination from physicians did not require them to be inordinately enforced.

In fact, under the Obama administration, there were only 10 cases citing conscience protections. Under Trump, this number tripled. However, there were 30,000 cases in 2017 where a patient felt like they were being treated unfairly because of their identity. Based on these numbers alone it’s clear that instead of strengthening conscience protection laws, the HHS should increase initiatives to protect patients from discrimination.

In the HHS budget brief for 2019, the importance of equal access to all patients is emphasized. However, because of these conscience protections, millions of people will be denied access to proper medical treatment.

Severino did not deny that LGBT-related cases may become a point of contention. Doctors could potentially refuse to prescribe PrEP, birth control and deny hormone therapy treatment to transgender individuals. Under Severino, the HHS division will support doctors who refuse treatment and also those who choose not to provide a referral to another doctor who would be willing to provide the patient with the care that they are seeking.

Although these conscience protections have substantive reasons as to why they exist — to protect the religious freedom most Americans cherish — the lines suggesting how and when they should be enforced become blurry. It is unclear whether they would allow medical practitioners to deny care for patients based on their sexuality or gender identity, but refusing treatment for a patient based on these attributes is extremely unconstitutional.

There is precedent from the California Supreme Court that protects patient’s rights over the religious views of physicians. In 1999, North Coast Women’s Care Medical Group refused to provide treatment for Guadalupe Benitez because she identified as lesbian. She claimed that the medical center provided the same treatment she requested to heterosexual women, but denied her. In 2008, the California Supreme Court ruled in her favor. The Court stated that businesses are not exempt from laws protecting clients from discrimination based on their own religious beliefs.

Additionally, the price for strengthening these protections is steep. In fact, the HHS estimated that it would cost $312 million in the first year and then another $126 million annually for the following years. These increased expenses are due to the expansion of the Conscience and Religious Freedom Division in the OCR and the costs of implementing new strategies to enforce the conscience protection laws.

All this money would be spent from taxpayer dollars when there aren’t even many cases where doctors complain about having to subvert their religious beliefs in order to care for patients to begin with.

In any case, doctors are supposed to transcend their moral and political convictions when they treat their patients.

In June 2016, at the Brocher Foundation, multiple bioethicists and philosophers formulated a general set of guidelines doctors should follow when treating patients.

They basically say that doctors should prioritize the well-being of their patients over their personal opinions. If they do have moral conflicts, they can refer their patients to another doctor. However, if no other doctor is available to complete the treatment they should administer it themselves.

The suggestions brought forth by this group recognize the importance of protecting every physician’s personal beliefs while also acknowledging the value of their patients. No doctor should feel forced to carry out procedures they are morally opposed to, but they should understand that if no other medical practitioner is able to perform their duties, it is their responsibility to carry out themselves. It is their job to care for, prioritize and address their patient’s medical needs.

Religious freedom is every American’s first amendment right. No one should ever feel like their liberties are being suppressed. However, this freedom for physicians should never come about at the expense of their patients. Especially when there are substantially more recorded acts of discrimination against patients than their medically trained counterparts.