There is No Such Thing as Chinese Food

One Student Chef Discovers the Nuances of the Cuisine With a Book, a Restaurant and a Recipe.

June 28, 2011

Published February 18, 2010

There is no such thing as Chinese food. What I mean is that there is no one cuisine. What we know as “Chinese food” is actually a reinterpretation of Cantonese food to fit American palates. Immigrants from Canton in southern China were the first to open restaurants in the U.S. and they adapted their ingredients and styles of cooking to cater to their customers.

To say that all Chinese food is the same is like saying all European food is the same. In the same way that there is Danish, French, Spanish and Russian food in Europe, the regions of China have differing culinary traditions

In her book “Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet and Sour Memoir of Eating in China,” Fuschia Dunlop describes her various journeys to parts of China as a culinary student. She focuses mostly on the Sichuan province, where she first learned to cook at the university in Chengdu.

Because of Dunlop’s intense descriptions of Sichuan food, I became a woman on a mission to find a restaurant in New York (with an English menu) that could deliver an authentic experience.

It was a long, soul-crushing search. Even in Manhattan’s sprawling Chinatown, a restaurant without a focus on fried rice is hard to find. You can be sure that if the menu is in Chinese they’re serving delicacies, but that clearly leaves me drooling by the door, watching happy families eating through the window, while I am unable to read the menu.

Finally, I ended up at Grand Sichuan Eastern. There are many Grand Sichuan’s in New York City. Some are part of a small chain; some are independent. I prefer the one on Second Avenue (1049 2nd Ave., 212-355-5855).

The entrance is unassuming: a window with a neon-yellow and red sign above ensures that this restaurant doesn’t stand out from all the other Chinese places in New York. Once inside, on a busy weeknight, someone will hurriedly seat you, perhaps squeezed-in next to another couple. The lucky diners in big groups can sit at large, round tables with a rotating lazy Susan in the middle, perfect for sharing the huge entrées. In the back of the (entirely bilingual) menu, there is a section called “American Chinese Food.” Please don’t make the mistake of ordering from here! While you might not be interested in the “jelly fish with scallion oil” appetizer or have a clue what “Chengdu’s Sister’s Rabbit” is, the “five-spiced beef” and “stir-fried pumpkin” are complex and delicious. And don’t forget to try the Dan Dan noodles.

Dunlop devotes an entire chapter to Dan Dan noodles in her book, saying that they were her saving grace while she studied at the university in Chengdu. Her descriptions of awakening the flavors at the bottom of the bowl when she first twirled chopsticks through the noodles are enough to make your mouth water. The Dan Dan noodles at Grand Sichuan Eastern is called an appetizer ($5), but one order is entrée sized.

But they are not for the faint-of-tongue. The first time eating Dan Dan noodles, my friend and I needed an entire pack of tissues and several glasses of water.

Dunlop’s book is peppered with recipes like this, and though curious and exciting (one recipe’s first ingredient is “one fresh bear’s paw”) they are mostly meant to enhance the experience of reading about her culinary journeys, and cannot be attempted by someone living thousands of miles from a Chengdu marketplace.

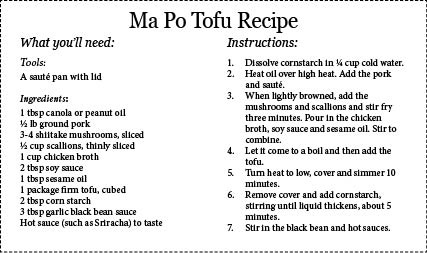

One Sichuan specialty that is more accessible, but still insanely delicious, is Ma Po tofu. It couldn’t be simpler to make and all of the ingredients can be found at Whole Foods. It has many of the flavors of Sichuan province, and the heat level can be adjusted to suit anyone’s palate. Leave out the pork for an exciting vegetarian dish.