Student Sleep Deprivation: The Importance of a Full Eight Hours

November 14, 2018

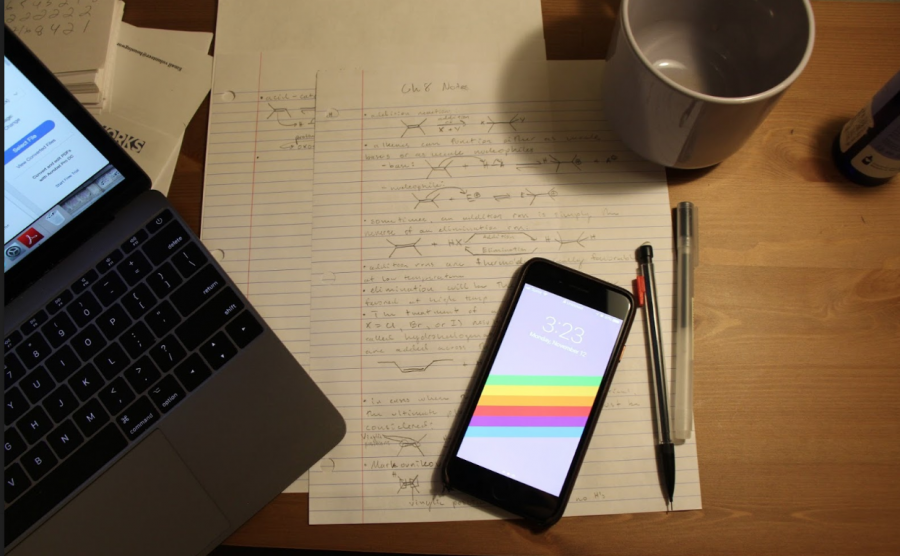

As students, we are constantly faced with the choice between work and sleep. This common trade-off is so characteristic of college students that sleep researchers seek out this population in order to study sleep deprivation and its effects. According to a study of 1,100 college students, 60 percent fell into the category of poor-quality sleepers.

Getting less than eight hours of sleep, waking up and going to bed at different times every day, and consistently using stimulants like caffeine to maintain wakefulness are all characteristics of poor-quality sleeping. Most often, college students blame the rigor and workload of their courses as reasons for their disrupted sleep schedules.

Neuroscience student Karel Van Bourgondien, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’21, struggles to keep consistent sleep schedules while pursuing his studies. Van Bourgondien generally gets between six and 12 hours of sleep per night, but he will resort to only three to six hours of sleep if he must. While handling a part-time job and the demand of the integrative neuroscience program, Van Bourgondien faces nights in which he closes up his place of work at 11 p.m., then continues to do homework when he returns home. Nevertheless, Van Bourgondien prioritizes sleep for upcoming exams: “If I’m studying for a test I know that at some point I won’t be able to retain anymore information until I’ve slept and subconsciously processed it.”

Research points towards sleep, rather than amount of time studying, as one of the major indicators of high test performance. In a study published in Current Biology, subjects were shown a series of images and required to recall the images on a test 48 hours later. One cohort was 35 hours sleep-deprived and the second cohort was well-rested. The sleep-deprived cohort scored 19 percent lower on the memory test than their well-rested counterparts.

Hope Vanderwater, FCLC ’21, is an environmental science major and finds it difficult to get a full eight hours of sleep on weeknights. She said that she usually gets between five and a half and seven and a half hours of sleep, citing schoolwork, her part-time job and hanging out with friends late at night as major factors disrupting her sleep schedule. However, Vanderwater noted, “Most commonly, if I’m intending to get seven [hours of sleep], I’ll accidentally get caught up on my phone and lose an hour of sleep.” To make up for the sleep she loses at night, Vanderwater will sometimes take naps after her classes; napping often helps her gain enough energy to continue working on her studies later in the night.

Like Van Bourgondien, Vanderwater prioritizes sleep especially before exams and when she is sick, though she did not always put sleep first. Vanderwater explained, “I’m realizing I have prioritized sleep more this year than last year and high school, because I now see that I function so much better when I’m rested.”

This better functioning Vanderwater mentions is evidenced greatly in the science of sleep. According to Fordham Professor of Chemistry Joan Roberts, Ph.D., there are two types of sleep that take place during a sleeping period: slow-wave sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. In REM sleep, “the brain, eye and body muscles are active,” Roberts said. REM sleep is also the period of sleep in which we dream. There are two subtypes of slow-wave sleep: delta sleep and theta sleep. The former is when deep sleep occurs, and the latter is light sleep. Characterized as “restorative” sleep, delta sleep involves the decrease of stress-related hormones and blood pressure and the increase of anti-aging growth hormone.

On top of the release of this growth hormone in delta sleep, the body removes oxidized neurotransmitters, which are toxic molecules formed in the brain during the daytime. Without delta sleep, these molecules accumulate in the brain and can lead to mental illness. Thus, anxiety and depression can arise from the lack of delta sleep. Moreover, inadequate amounts of delta sleep can enhance symptoms of pre-existing conditions like ADD and ADHD.

Most importantly, the amount of sleep an individual gets greatly affects their immune system. Sleep deprivation is often a factor that can render an individual susceptible to infectious disease and even cancer. Roberts attributes these outcomes to the circadian nature of the immune system.

The term circadian refers to the rhythmic fashion in which humans and other animals fall asleep and wake up. The circadian rhythm takes place in a 24-hour period and is regulated by the environment and internal clocks with our brains. Various sleep hormones are produced only under certain light conditions. For instance, the brain produces melatonin only under dark-light conditions. This period usually arises between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. Melatonin is crucial for delta sleep to occur, and even with normal nighttime darkness, only 15 percent of the eight-hour sleep period is delta sleep. Exposure to blue light converts melatonin to serotonin, a neurotransmitter associated with wakefulness. Even the slightest blue light, like the light from a phone or a bathroom light, can prevent the production of melatonin.

Due to the circadian nature of the human body’s reparative systems, consistent and ample amounts of sleep are crucial to human health. As young adults, the health decisions we make now will affect our overall health greatly in the future. Moreover, the habits we develop now will last us our lifetime, so it is imperative to correct our sleep schedules. Thus, professors, students and administrators should work towards a learning environment that reconciles course rigor with personal well-being.