In Harlem, Following History

Fordham Alumni Explore one of New York City’s Fastest-Gentrifying Neighborhoods

JEFFREY UMBRELL AND STEPH LAWLOR/ THE OBSERVER

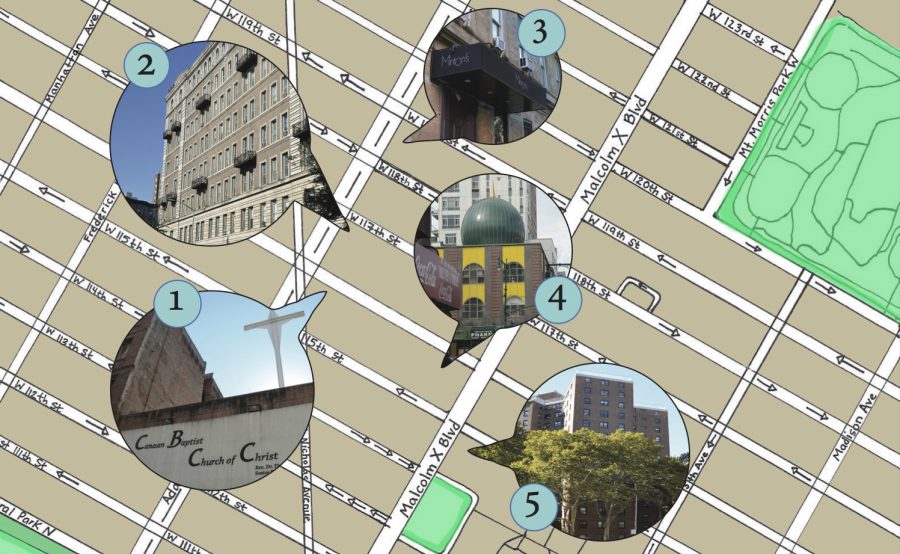

The locations on the above map correspond to descriptions below.

November 7, 2018

On the morning of Oct. 7, Fordham History and African American Studies Professor Mark Naison traveled to 116th Street in Harlem early to explore the neighborhood before joining a group of 15 or so alumni on a walking tour organized by the Office of Alumni Relations. The neighborhood, he said, was “unrecognizable” to him. “I see all these white tourists heading out of the subway and crowding the streets … ‘Tourism’ and ‘gentrification’ are words that no one would have ever associated with 116th Street in the ’90s.”

The mostly white Fordham group was just one of many visiting the neighborhood that morning, and it was clear that, as across much of New York City, gentrification was quickly making its way into Harlem, which is historically viewed as one of the black capitals of the United States.

“Luxury condominiums on 116th Street? Crowds of tourists? This blew me away,” Naison said.

Alumni Relations plans a number of cultural tours and museum visits across New York City each year. Shannon Quinn, the office’s associate director of New York City programming, organized the Harlem walking tour in conjunction with Naison.

“Many of the alumni who attend our NYC events attend fairly regularly,” Quinn said. “My goal is to build community and engagement among our alumni.” She stressed that attendees have a “shared interest” in the events’ content. These events allow alumni to engage and connect with one another.

“I think it’s a great program,” Naison said of the work done by Quinn and Alumni Relations. “For me, it’s all very exciting. I’m glad to see tours like this being organized.” Many of the sites highlighted on the tour were nestled among the luxury condominiums and high-rises of which Naison spoke, and one has to hope that they, too will not be lost to the at times destructive power of gentrification.

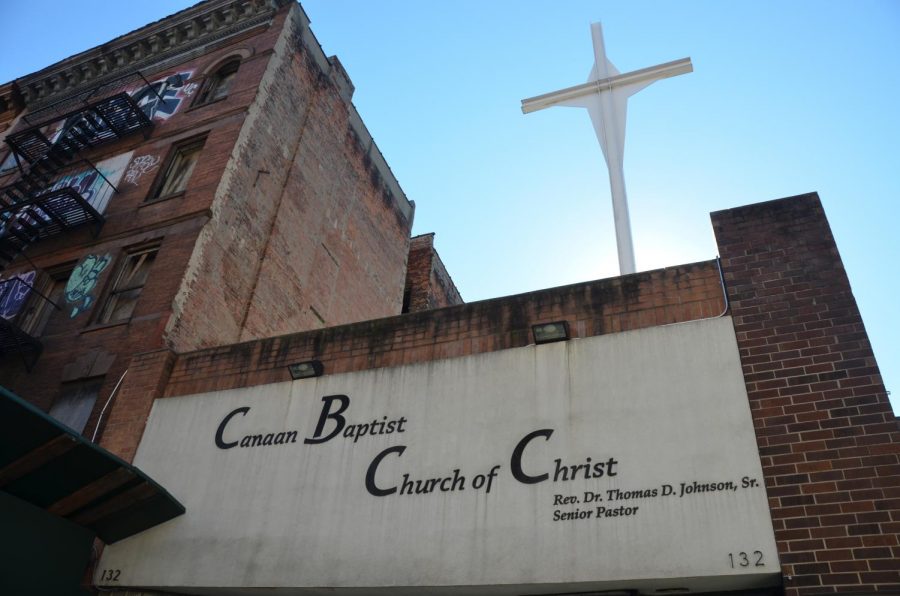

1. Canaan Baptist Church – 132 W 116th St.

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

The worship hall of the Canaan Baptist Church can only be found after passing through the deceptively small and inconspicuous brick-and-concrete entrance and down a long, windowless and similarly modest hallway. Doing so, however, only makes the size of the hall itself all the more impressive. In 1965, the congregation moved from the church’s previous location two blocks north to the present building, a renovated Loews Theater, as Canaan was quickly becoming one of the largest religious communities in Harlem. Red is the color of the carpet, curtains and robes worn by pastors, ministers and choir, and its brightness is reflected in the energy and spirit of the attendees who fill Canaan’s two levels of seating.

2. Graham Court Apartments – 1921 Adam C. Powell Blvd.

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

Graham Court, which occupies in length the entire block from 116th to 117th Streets, dwarfs the rows of walk ups that surround it and serves as a reminder of the radical changes Harlem underwent since the turn of the 20th century. Completed in 1901 at the commission of William Waldorf Astor, the wealth that Graham Court represented had all but left Harlem by the 1920s, and the building quickly fell into a state of disrepair. It has since been meticulously renovated, and its wrought iron fence, corinthian columns and arched entryway offer a glimpse into a past where Harlem was in fact an uptown retreat for the extremely wealthy.

3. Minton’s Playhouse – 210 W 118th St.

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

The original Minton’s Playhouse closed in 1974, and this renovated restaurant tries to capture some of the energy that musicians like Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald brought when they graced the Minton’s stage. “I could learn more in one session at Minton’s than it would take me two years to learn at Julliard,” Miles Davis wrote of the club’s legendary jam sessions in his 1990 autobiography, sessions that would help to develop the heavily improvisational nature of bebop and cement Minton’s place in music history.

4. Malcolm Shabazz Mosque – 102 W 116th St.

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

Walking past the corner of 116th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard, one may not even notice the presence of the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque, formerly known as Mosque No. 7. A barbershop, shoe repair store and pharmacy occupy its ground floor, and its green and gold dome is only visible from the opposite side of the street. The mosque, nonetheless, is one of the most historically significant sites in Harlem and stands as a monument to the neighborhood’s rich Islamic history. Malcolm X preached here until his conversion to Sunni Islam in 1964. In 1965, the building was destroyed by firebombing, but has since been rebuilt save for the fourth floor.

5. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Towers – NYC Housing Authority – Malcolm X Blvd. and 115th St.

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

JEFFREY UMBRELL/THE OBSERVER

Malcolm X and other Civil Rights leaders once preached on street corners in and around these public housing towers, which are by far the tallest in the neighborhood. They have stood witness to the tumult of the 1960s, the Harlem drug epidemics of the 1980s and 1990s and now remain one of the last vestiges of truly affordable housing in the area as gentrification slowly creeps uptown. The towers are just one section of a public housing development that stretches from Malcolm X Boulevard (the northern extension of 6th Avenue) almost to the shore of the East River.

“If you are not living in public housing, where the rents are protected,” Dr. Naison explained, “your chances of being displaced are pretty good over the next 10 years.” He worried that poorer communities who have left Harlem for the Bronx will eventually be pushed out of New York City altogether.