Meet Clint Ramos, the Tony-Winning New Head of Design and Production

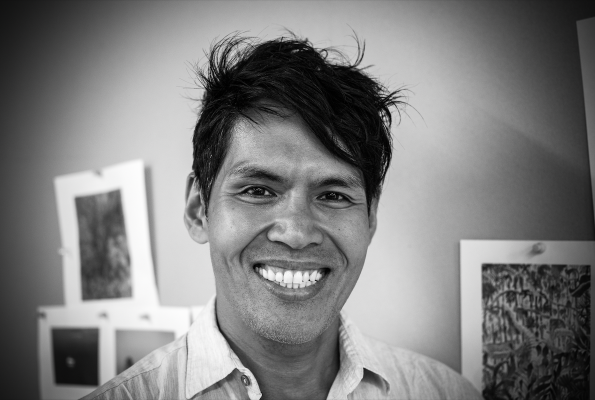

Clint Ramos is the new head of design and production for the Fordham Theatre Program (Andrew Beecher/The Observer).

September 26, 2018

There was a lot happening around me as I sat in the second floor cafe of the Signature Theatre waiting for Clint Ramos. To my left, preteens in bright red T-shirts were animatedly chatting about “Be More Chill” while perusing the show merchandise as their parents ordered a special “Rich Set a Fire-Ball” cocktail from the bar. To my right, a group, presumably of theater creatives, was having an intense meeting, scripts in one hand, highlighters or pens in the other. I situated myself right in the middle of these two groups so I could be on the lookout for Ramos, one eye on the stairs, the other on the Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, where his latest show, “The True,” was preparing for its first preview.

Those unfamiliar with Ramos will undoubtedly be hearing his name much more frequently on campus. The Tony-winning costume designer has just joined the Fordham Theatre Program faculty as the new head of design and production. As I sit, nervously going over the questions in my head, I see Ramos round the corner, beaming and waving at me as I stand to acknowledge that I was the student he was looking for.

From the moment he and I began to talk, no one would have been able to guess that we had just met. Ramos was warm and welcoming, deeply invested in our conversation, as I could tell he was absorbing each word I said. It is this obvious outward investment in young people that makes Ramos such a valued mentor.

“I’ve always loved teaching. Throughout my life, I’ve felt that the people that I’ve been really, completely honest with, who have been instrumental in me forming an assessment about who I [am] have been those that mentored me, have been my teachers,” he told me. “I’ve made a decision in my life that if I could teach I would.”

Ramos comes to Fordham after spending the past several years teaching at other universities — New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, Georgetown and SUNY Purchase. Though this is his first teaching position at Fordham, it is not his first experience with the university.

“Early on in my career, I actually designed one show at Fordham [in 2007], Brecht’s ‘Man Equals Man,’” he shared before continuing, “but I’ve also had a lot of colleagues in the theater who have gone to Fordham, who were products of the Fordham Theatre Program. I have high respect for them and I have always admired them.”

Though Ramos didn’t name any of his colleagues who were Fordham alumni, I couldn’t help but speculate which fellow Rams he could have been speaking of. Tony-winning actor John Benjamin Hickey, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’85, whom Ramos worked with in 2017’s Tony-nominated play “Six Degrees of Separation”? Frank DiLella, FCLC ’06, the Emmy-winning host of NY1’s “On Stage”?

The Signature’s cafe grew louder as more and more excited kids piled into the area, buzzing with excitement over “Be More Chill.” I take this moment to take a step back from Fordham to ask Ramos about another pivotal experience in his life: winning his first Tony Award (on his first nomination, no less) for 2016’s “Eclipsed.”

“I literally blacked out,” he told me, as I started to laugh. Ramos leaned in and started to frantically explain what caused this episode as I listened in awe. For those unfamiliar with the Tony Awards, the one thing you need to know to understand Ramos’ story is this: the ceremony is long and there is no food to be found.

Like any good son, Ramos brought his mother from the Philippines as his date for the evening. Just as they began to call out the names of the nominees in his category, which was the first award of the evening, Ramos’ mother, a diabetic, started to have a hypoglycemic attack.

“She was like, ‘Where are those snacks that you brought?’ and so I’m digging, digging,” Ramos recalled as he mimicked frantically searching through a bag for food. “They’re calling the category and here I am, digging, digging, digging, digging, for this thing. I hand it to her. I thought they called my name and when I looked up at my mother [she] was, like, up on her feet clapping. And I realize, ‘Oh, my God, they called my name.’

“So I went down. I go on that stage. I look out. The first face I see is Oprah. And then I think, ‘No, no, no, you can’t look at Oprah; that’s going to be trouble.’ So I moved my sight,” he said as he moved his head from side to side. “There was, like, a celebrity everywhere. I move my sight and Jessica Lange … I literally just blacked out and forgot everything I was supposed to say [even though] I had this like long planned speech.

Ramos and I laughed together before he paused and took up a more serious tone. “I’m the first person of color to ever win [that award],” he shared. “I will never forget that night. It truly changed my life. It showed the world what great American theatre is, that it is all embracing, all encompassing, [and will] welcome you with open arms.”

After I shared my sympathies with him (Oprah could cause even the most composed person to lose it), our brief Tonys digression comes to an end and Ramos and I return to discussing his prolific career in the theater. I’m curious, how does a child from a family of lawyers in the Philippines end up as a Tony-winning designer in New York?

“When I was growing up, I always felt like an outsider. I was gay. I was overweight. The sense of being of excluded or self-exclusion … has always sort of been present in my life,” he told me. Then he discovered theater. “Theater had become an outlet, although I didn’t realize that I was participating in a theatrical process as a kid. The art had always been this sort of this outlet for me to express myself without the approval of others,” he said.

His first major theatrical influence came in the form of a drama teacher at the boarding school he attended in Manila. This was a pivotal time in the history of the Philippines. The country was under the control of Ferdinand Marcos, who was president from 1965 to 1986. His time as president has been described as a “grisly one-stop shop for human rights abuses.” The teacher took Ramos under his wing, exposing him to a type of street political theater whose main goal was to enact change. “I saw the power that theater could have,” he said. “It could be a method for change.”

This revelation transformed how Ramos thought not just about himself, but the work he strived to do. Now, he tells me that he has made it a rule for himself that he will only work on projects that matter or with people who challenge him “politically, socially and intellectually.”

This personal mission of his is the message he hopes to impart to his students: that theater is a catalyst for change and as theater makers, they are responsible for that change.

“I would love for [my students] to walk out knowing that they’re a human being with a voice. I encounter so many young people who seem aimless, voiceless. I want my students to come out of my classes having really formed a solid identity and knowing that they can make a mark in this world and that they have a voice to change this world.”