“If You Were Angry Enough, Fordham Would’ve Closed”

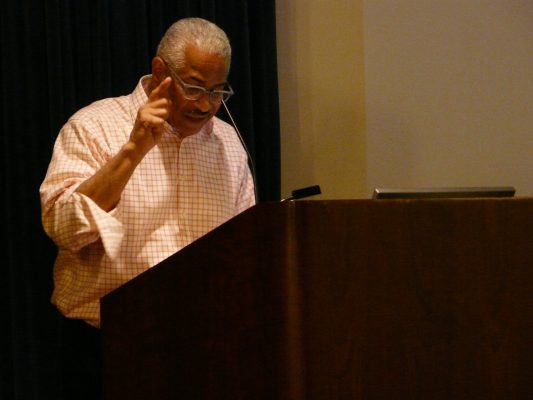

Felipe Luciano was a co-founder of New York City’s Young Lords in the late sixties. (COLIN SHEELEY/THE OBSERVER)

March 14, 2018

“Folks, you’re not angry enough.”

Felipe Luciano stared out at the crowd within Rose Hill’s Flom Auditorium during his speech on Feb. 21, pausing to let his statement sink in. The event, presented by the Bronx American History Project, had taken a somber turn after it began as a celebration. Musical group Bambula drew several audience members out of their seats to participate in the onstage performance. Yet those same people who had danced minutes before now sat quietly in their seats, nodding along to Luciano’s statement. The music had stopped, and now it was time to listen.

“What I don’t understand is how we read and take the education superficial concepts of blackness, and do not get angry?” Luciano said. “I don’t see righteous indignation in this city, and I don’t see it in the nation.”

Luciano is no stranger to student activism. Before he became a journalist and a political figure, he was the co-founder of the New York branch of the Young Lords, a left-wing Puerto Rican organization that stressed the importance of self-determination and community service, as well as self-defense against oppression. Resistance, particularly the outrage that causes it to occur, seems to be lacking in Luciano’s eyes, especially when the country is at “the precipice of the wildest ride” he has witnessed since 1939.

“If you were angry enough, Fordham would’ve closed down,” Luciano said. “Schools would have been closed down. McDonald’s would have been shot to the ground. Goya would’ve been thrown out.”

The reasoning, Luciano believes, lies not just in policy, but in a deeper issue facing the affected communities.

“Part of the reason for our lack of righteous indignation—and I was talking to the chair of the Black Panther Party Bobby Seale about this—is that we are not black enough,” Luciano said.

The panel directly after Luciano’s speech, featuring journalist Janel Martinez, activists Sessle Sharpe and Vanessa Reyes, and Fordham graduate Aixa Rodriguez, explored the nuances of color and culture further, as individuals shared their personal experiences throughout their years as children, students and adults of Afro-Latin descent. The first question, asking each speaker to explain how they would describe their identity, prompted insightful and detailed answers into the complications of trying to live as a member of both the black and Latino community.

Reyes spoke about her mother’s influence in forming “an unapologetic blackness.”

“She always made sure that I knew, especially going up to contexts like elementary school,” Reyes said. “People would question me because of how I appear and my last name, so she made sure that I knew I was a black woman, and I just so happen to have hispanic or Latin American heritage.”

Sharpe, a 25-year-old man of Afro-Cuban descent, described growing up in the South and how many people responded to his heritage, saying that by leaving his community, he was able to understand his full identity.

“In the South you’re black to someone. You’re Black. Doesn’t matter what language you speak, if you speak French, Spanish, it’s like you’re Black. And you can’t run from that. So me growing up, I couldn’t run from that,” Sharpe said. “So when you have people like me who try to speak Spanish or a different language, people would question like, what the hell are you?”

Luciano also stressed the similarities between African and Puerto-Rican communities, learning about one another through shared family values, food, and culture. Through those similarities, Luciano said that it has formed into a “cultural strength,” one that needs to be solidified as a “political angle.”

“I believe that I was put I am here for a reason,” Luciano said. “I hope that this movement that we’re talking about-Puerto Rican, Latino, black folk-that we begin to understand that we are family.”