Five Weird, Rude, Inspiring Books Representative of New York City

June 27, 2011

Published: November 19, 2009

New York City, like literature, is always changing; no two neighborhoods or two books evoke the same experience, and sometimes revisiting any one of them leads to an entirely different place. Both are fawned over by many while meaning entirely different things to each of their admirers. Consequently, all that makes literature and the city so pliable to individual whims also makes any opinion on them distinctly singular.

A discussion of the literary representation of New York seems almost absurd without mentioning renowned classics like Pulitzer Prize winner Edith Wharton’s “The Age of Innocence,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” or Truman Capote’s “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” among others. This list includes none of them. That’s not the city I know, not the city I’ve seen, dreamed, loved and hated. Maybe tomorrow it will be. For now, here are the five books that best represent my New York:

“Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York” by Luc Sante: Luc Sante’s honest, gritty look at the birth of New York City provides a perfect introduction to a literary crash course on the city’s history. Focusing on the underbelly of 19th century Manhattan, areas like Hell’s Kitchen, the Bowery and Hell’s Hundred Acres—its name now demoted to “SoHo”—are presented at their most devilish and archaic. Feverishly researched and historically sound, a grid-less Manhattan comes to life, full of squatters and profiteers, each looking wide-eyed toward the future without a clue how to get there. Sante, like an archeologist, digs at the earth of the city to find its early remnants, uncovering its most primal truths and motivations. In true New York fashion, he goes straight for the dirt.

“Bright Lights Big City” by Jay McInerney: The hedonism of old New York moves uptown into the 20th century in this brilliant novel about a yuppie down on his luck. Obsessed with the trappings of the 1980s Manhattan high life, the nameless narrator loses sight of himself in a sea of drugs, greed and women. When his beautiful wife leaves him, he becomes consumed by the thought of her and his ever-growing need to uphold the guise of his superficial lifestyle. Narrated in the second person, “Bright Lights Big City” literally puts “you” in 1980s New York, as both a victim and a beneficiary of the turbulent, selfish decade. While other novels have commented upon yuppie culture in New York City before, most famously in Bret Easton Ellis’ satire “American Psycho,” few have done it in such a clear and cautionary way. As a result, McInerney’s novel serves not only as a history lesson of the bygone Reagan era but also as a moral warning to the “Sex and the City” generation in a city slammed by a recession yet growing increasingly gluttonous and homogenized.

“Chronicles: Volume 1” by Bob Dylan: Bob Dylan’s first installment of his spellbinding autobiography isn’t entirely about New York per se, but you’d be forgiven to mistake three of its five chapters as the great, lost look at New York: a portrait of a man and his city that seems fictional in the ease with which it dispenses scene after scene of urban cool. The precocious narrator is none other than Dylan himself, forever straddling the line between reality and fantasy, reminiscing about, and appropriating, America’s peculiar history. The city’s bustle and endless winter transforms him from Minnesota’s Zimmerman to New York’s Dylan as he hones his talent in the backs of Greenwich village hideaways, eating middle-of-the-night burgers at the Café Wha?, meeting heavyweight champions in red leather upholstered booths, playing impromptu sets at the Gaslight, riding the D train to Brooklyn’s Paramount Theater, watching art films on 12th Street, and building his own wooden furniture in his slummy Village apartment. Emerging from the ooze of the cultural epicenter of America, he criss-crosses the city streets as an unknown endlessly namedropping everybody from Balzac to Faulkner and Judy Garland to Hank Williams. Dylan’s book is steeped in New York’s history but it does not feel retrospective; its images are immediate. Even the gorgeous cover photograph features Times Square as Bob saw it when he arrived there for the first time on a rainy night in 1961, a gateway into the mysteries of the city, past, present and future.

“Please Kill Me” by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain: After the jazz age subsided, the Beats lost Kerouac to drinking and New York lost Dylan twice (first to fame, then to gospel music), there was a new cultural beast in town: punk. And little else outside of the odd Scorsese movie seems to capture the grit and nihilism of 1970s New York City as perfectly as Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s oral history of the scrappy, freaky movement. While talk of the emergence of the CBGB’s scene in the late ’70s usually devolves into cliché-raddled memories of punk yore, here we get a frighteningly intimate and realistic view of kids making things up as they go, during one of the most dangerous and creative periods in the city’s history. Composed of first-hand accounts scoured from hundreds of interviews, the book throws the reader headfirst into the Bowery, alongside the likes of Andy Warhol, the Ramones, Blondie and Lou Reed. Among the most unbelievable snapshots of the city’s decline is that of a trip home from CB’s gone wrong, in which the drummer from influential band the Dead Boys is stabbed by criminals on Fifth Avenue, culminating in a narrow escape from police in the blood-soaked backseat of a taxicab. “Please Kill Me” captures New York City at its most apocalyptic but also at a time when a tremendous sense of freedom emanated from the island of Manhattan, unrivaled by its whitewashed, corporate shadow today.

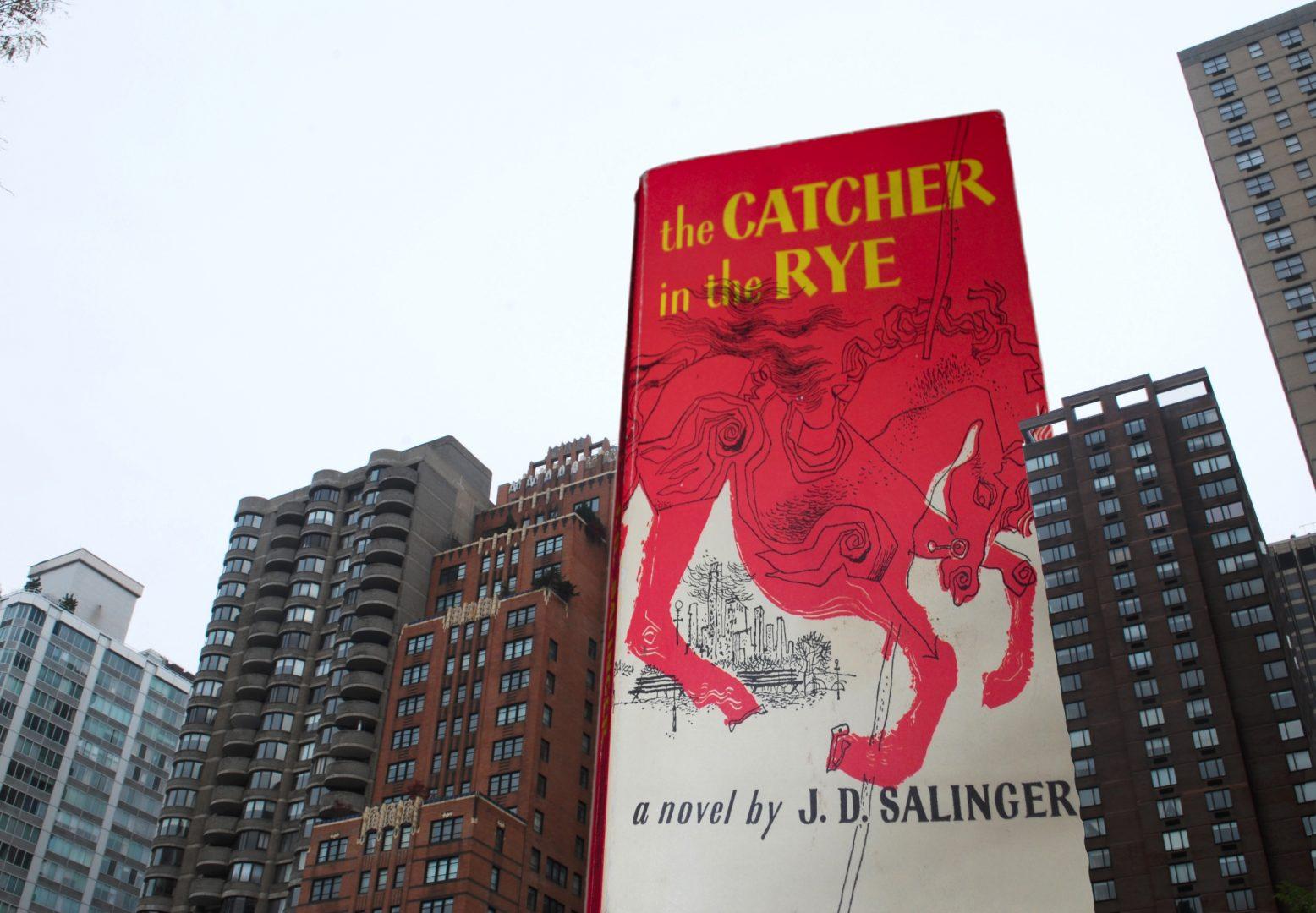

“The Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger: Though it’s become a rite of passage for teenagers all over the world, J.D. Salinger’s controversial story of disenchanted youth endures as a New York tale. Hoping to escape the manicured lives of his peers and tormented by both the death of his brother and his estrangement from his younger sister Phoebe, Holden Caulfield returns to the city in which he grew up but does not return home to his parents. Instead, after hopping the train, he makes a perpetual detour to explore the particularly adult world of midtown Manhattan. The 16-year-old narrator confronts his experiences frankly and directly, generally unphased by his inebriated run-in with a prostitute and the sexual advances of a former teacher, relaying his experiences plainly to the reader like a friend. Finally, after he reconnects with Phoebe, bringing her to the Central Park carousel, he is overwhelmed upon seeing her ride it, intoxicated with her purity but terribly saddened by its inevitable demise.

Salinger’s work endures because it effortlessly captures the previously little-explored longing of modern Americans for innocence, for safety and for independence, in an odyssey of the disenchanted. Anyone who has journeyed to New York City for the first exciting time has fashioned himself as his own Holden Caulfield. His story has plunged its roots inextricably into the city’s history. As I walked in the park with a friend one day, we passed the carousel and I mentioned that infamous scene in “Catcher”; he looked at me perplexed. I was sad, not because he hadn’t read the book, but because he couldn’t understand that damned carousel.